(Updated Sept. 22, 2022)

The strained relationship between Cardinals owner Gussie Busch and pitcher Steve Carlton had its roots in a dispute which occurred two years before the ill-fated trade of the future Hall of Famer.

On March 12, 1970, after Carlton refused to accept the club’s salary terms, Busch said, “I don’t care if he ever pitches a ball for us again.”

On March 12, 1970, after Carlton refused to accept the club’s salary terms, Busch said, “I don’t care if he ever pitches a ball for us again.”

Carlton and the Cardinals eventually agreed on a contract, but Busch held a grudge.

Two years later, when Carlton again balked at the Cardinals’ contract offer, Busch ordered general manager Bing Devine to trade the pitcher.

Dealt to the Phillies on Feb. 25, 1972, for pitcher Rick Wise, Carlton was one of the game’s all-time best left-handers, winning four Cy Young awards, compiling 329 career wins and earning election to the Baseball Hall of Fame.

Bitter Busch

After helping the Cardinals win consecutive National League pennants in 1967 and 1968, plus a World Series title, Carlton developed a devastating slider and posted a 17-11 record and 2.17 ERA in 1969. He also became the first major-league pitcher to strike out 19 batters in nine innings.

Entering spring training in 1970, Carlton, 25, told the Cardinals he wanted a salary of $50,000. The Cardinals, who paid Carlton $24,000 in 1969, gasped and responded with an offer of $30,000 for 1970. Carlton countered with an ask of $40,000, but the Cardinals “refused to budge” from the $30,000 figure, the St. Louis Post-Dispatch reported.

Busch asked Carlton to accept the club’s terms and assured him the Cardinals “would make it up to him” if he produced a good season in 1970. After Carlton rejected the proposal, Busch told the Sporting News, “I don’t like his attitude, not a damn bit.”

In a rant reminiscent of his public scolding of the players in a 1969 spring training clubhouse meeting, Busch said, “The fans are going to resent this situation. I can’t understand it. The player contracts are at their best, the pension plan is the finest, the fringe benefits are better, yet the players think we are a bunch of stupid asses.

“I’m disillusioned,” Busch said. “I don’t know what’s happening among our young people, to our campuses and to our great country.”

Busch got support from the editor and publisher of The Sporting News, C.C. Johnson Spink, who wrote, “We believe fans in general will agree with Busch in his challenge to the other owners to join him in resisting some of the players’ demands.”

Surprise settlement

Carlton said he wouldn’t ask for a trade and Devine said he had no plans to deal the pitcher.

A day after Busch said he didn’t care if Carlton pitched again for the Cardinals, Carlton told the Post-Dispatch, “I intend to pitch, but I want to meet Bing again and try to solve this.”

Post-Dispatch sports editor Bob Broeg noted, “Carlton has kept his composure in the face of Busch’s unfortunate comment that he didn’t care if Steve ever pitched again for the Cardinals.”

Broeg concluded, “The Redbirds need the big left-hander, one of baseball’s best young pitchers.”

On March 17, 1970, Carlton signed a two-year $80,000 contract with the Cardinals. According to multiple published reports, the deal paid Carlton $30,000 in 1970 and $50,000 in 1971.

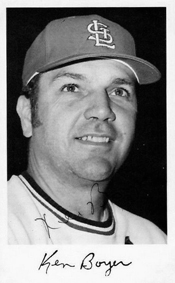

Carlton became the first Cardinals player to receive a two-year contract since third baseman Ken Boyer (1960-61).

“I never thought I’d sign a two-year contract, but this is a fair way to handle the situation and I’m very happy,” Carlton said.

Cardinals executive vice president Dick Meyer, who brokered the compromise, said, “This enabled both sides to maintain a posture and was fair to both of us _ to Steve and to the club.”

Get rid of him

In 1970, the first year of the contract, Carlton was 10-19. In the second year, 1971, he was 20-9.

The Cardinals reportedly offered Carlton a 1972 salary of $57,500. As spring training got under way, he remained unsigned. Carlton said he and the club were less than $10,000 apart, The Sporting News reported, but Busch was angry when the pitcher didn’t sign.

In an appearance at a January 2015 charity event at the Doubletree Hilton in St. Louis, Carlton recalled the negotiations with Busch. “I didn’t have an agent. I have one semester of junior college and I’m going up against a beer baron. He was a maniac and I didn’t know much about anything.”

In his book, “The Memoirs of Bing Devine,” Devine said, “Mr. Busch wanted him gone.”

“This thing was generated by our difference with Carlton two years ago,” Devine told the Sporting News after dealing Carlton to the Phillies. “Having gone through that experience, we could sense a similar situation developing.”

The Phillies signed Carlton for $65,000 in 1972. Though the 1972 Phillies finished in last place in the East Division with 59 wins, Carlton was 27-10 with a 1.97 ERA. He was 4-0 against the Cardinals.

Carlton, who was 77-62 as a Cardinal, pitched 24 years in the majors and was 329-244. He ranks second all-time in career wins by a left-hander. Warren Spahn has 363.

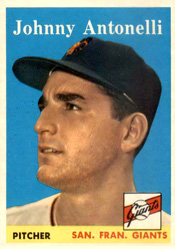

A left-handed pitcher, he had a 126-110 record in 12 major-league seasons with the Braves, Giants and Indians.

A left-handed pitcher, he had a 126-110 record in 12 major-league seasons with the Braves, Giants and Indians. In March 1970, Boyer attended spring training with the Cardinals for the first time since he was traded five years earlier.

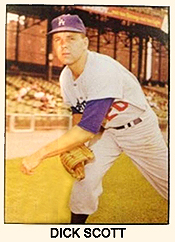

In March 1970, Boyer attended spring training with the Cardinals for the first time since he was traded five years earlier. A left-handed pitcher, Scott was in his eighth season in the minor leagues when he got called up to the Dodgers for the first time in May 1963.

A left-handed pitcher, Scott was in his eighth season in the minor leagues when he got called up to the Dodgers for the first time in May 1963. On Feb. 27, 1990, the Cardinals acquired Olivares, a right-handed pitcher, from the Padres for outfielder Alex Cole and reliever Steve Peters.

On Feb. 27, 1990, the Cardinals acquired Olivares, a right-handed pitcher, from the Padres for outfielder Alex Cole and reliever Steve Peters. A grand jury indictment named Dean, 60, a co-conspirator in a gambling scandal on Feb. 24, 1970.

A grand jury indictment named Dean, 60, a co-conspirator in a gambling scandal on Feb. 24, 1970.