Babe Didrikson, who won Olympic medals in track and field before she became one of America’s top golfers, was the starting pitcher for the Cardinals in a spring training game.

On March 22, 1934, Didrikson pitched for the Cardinals against the Red Sox at Bradenton, Fla.

On March 22, 1934, Didrikson pitched for the Cardinals against the Red Sox at Bradenton, Fla.

A relentless self-promoter, Didrikson’s performance helped develop her reputation as America’s premier woman athlete.

Diamond dandy

A daughter of Norwegian immigrants, Didrikson was born in Port Arthur, Texas, and grew up in nearby Beaumont, where she excelled in multiple sports.

At 21, she was a member of the U.S. Olympic track and field team. At the 1932 Summer Olympics in Los Angeles, Didrikson won two golds (hurdles and javelin) and a silver (high jump).

With America in the grip of the Great Depression, opportunities for women in professional sports were limited. Didrikson sought to earn income in several sports, including basketball, billiards and baseball.

In 1934, Didrikson joined the House of David barnstorming baseball team. Promoter Ray Doan arranged for Didrikson to have a training session with Cardinals pitcher Burleigh Grimes in Hot Springs, Ark.

According to the Associated Press, Didrikson “would be one of the best prospects in baseball if she were a boy,” said Grimes.

The Associated Press also noted, “The Babe has mastered somewhat of a curve.”

Timely fielding

The Athletics and Cardinals each agreed to let Didrikson pitch an inning in a spring training game.

On March 20, 1934, at Fort Myers, Fla., Didrikson started for manager Connie Mack’s Athletics against manager Casey Stengel’s Dodgers before a Tuesday afternoon gathering of 400 spectators.

Didrikson walked the first batter, Danny Taylor, and hit the next, Johnny Frederick, with a pitch.

The No. 3 hitter, Joe Stripp, lined the ball. Second baseman Dib Williams caught it for the first out and tossed to shortstop Rabbit Warstler, who tagged second to double up Taylor, who had headed for third. Warstler threw to first baseman Jimmie Foxx to nip Frederick, who couldn’t get back to the bag in time, and complete a triple play.

According to the book “Diz,” a biography of Dizzy Dean, Stengel shook his head in mock sorrow and said, “My little lambs just couldn’t get to her.”

“The Babe was wildly cheered as she left the premises,” the Philadelphia Inquirer reported.

Didrikson, a right-hander, stood between 5-foot-5 and 5-foot-7 and weighed between 115 and 145 pounds, according to varied sources. She “looked like a slightly built boy except for a few stray feminine locks that stuck from under her black baseball cap,” the Fort Myers News-Press reported. “She possessed a slow curve but had some difficulty in finding the plate.”

With her inning of work done, Didrikson was lifted and the Dodgers won, 4-2.

Tough break

Two days later, before a Thursday afternoon crowd again estimated at 400, Didrikson made her start for manager Frankie Frisch’s Cardinals against manager Bucky Harris and the Red Sox.

Didrikson “is gaining experience and improving her pitching,” the St. Louis Post-Dispatch reported. “Under the tutelage of Burleigh Grimes, Dizzy Dean and others, she has learned to stand on the rubber, wind up like a big-leaguer and throw a rather fair curve.”

Joining Didrikson and Frisch, who played second base, in the Cardinals’ starting lineup were first baseman Rip Collins, shortstop Burgess Whitehead, third baseman Pepper Martin, left fielder Joe Medwick, center fielder Buster Mills, right fielder Jack Rothrock and catcher Spud Davis.

After Red Sox leadoff batter Max Bishop grounded out to second, Didrikson allowed singles to Bill Cissell and Ed Morgan, putting runners on second and first.

Cleanup hitter Roy Johnson grounded to Frisch, who threw to Whitehead, covering the bag at second, for the force on Morgan.

With two outs and runners on third and first, rookie Moose Solters faced Didrikson next. Didrikson got two strikes on Solters and threw a curve. Solters watched it go into the catcher’s mitt. To press box observers, the pitch was strike three, which should have ended the inning, but the umpire called it a ball.

Solters hit the next pitch for a two-run double.

Didrikson “deserved a better fate than she received,” the St. Louis Globe-Democrat reported. “A hit followed what could have been called a third strike and the third out.”

The St. Louis Star-Times declared Didrikson would have escaped with a scoreless inning “but for a questionable decision by the umpire.”

On the links

After Solters doubled, Dusty Cooke reached on an error by Rip Collins. Rick Ferrell singled, scoring Solters and giving the Red Sox a 3-0 lead. Didrikson got the next batter, Bucky Walters, to fly out to left.

The Red Sox “would have been scoreless if it had not been for loose fielding and what the Cards described as the plate umpire’s failure to see a third strike as a strike,” the Post-Dispatch reported.

The Cardinals rallied for three runs in the bottom of the first against Fritz Ostermueller. Whitehead, the eighth-place batter, made the last out of the inning, depriving Didrikson of a plate appearance.

Bill Hallahan relieved Didrikson in the second and pitched four innings. Dean, who told Didrikson he’d show her some “real chucking,” pitched the last four, held the Red Sox hitless and the Cardinals won, 9-7. Said Dean: “I had them swinging like ham on a hook.”

“Well, our Red Sox managed to get three runs in one inning off Babe Didrikson, the girl athlete,” the Boston Globe declared. “So perhaps later on they will be able to play ball with the boys.”

Columnist L.C. Davis of the Post-Dispatch concluded, “As a pitcher, Babe is an outstanding field and track athlete. Babe may be a drawing card, but a woman’s place is on the bench.”

Three days later, Didrikson pitched two scoreless innings for the minor-league New Orleans Pelicans against the Cleveland Indians.

Didrikson eventually focused on golf. At the 1938 PGA Tour Los Angeles Open, where she competed against the men, Didrikson met professional wrestler George Zaharias. Eleven months later, in December 1938, they married in St. Louis and she became Babe Didrikson Zaharias.

A founding member of the LPGA Tour, Babe Didrikson Zaharias won 41 titles, including 10 majors. She was a three-time winner of the Women’s U.S. Open, including in 1954 after she underwent surgery for colon cancer.

Babe Didrikson Zaharias was 45 when she died of cancer in 1956.

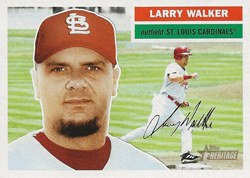

Walker, a three-time National League batting champion who was elected to the Baseball Hall of Fame on Jan. 21, 2020, played his first six seasons in the majors with the Expos and became a free agent in October 1994, the same month Jocketty replaced

Walker, a three-time National League batting champion who was elected to the Baseball Hall of Fame on Jan. 21, 2020, played his first six seasons in the majors with the Expos and became a free agent in October 1994, the same month Jocketty replaced  Collins, 37, signed a minor-league contract with the Cardinals on Feb. 16, 1990, and was invited to audition for a spot with the big-league club at spring training.

Collins, 37, signed a minor-league contract with the Cardinals on Feb. 16, 1990, and was invited to audition for a spot with the big-league club at spring training. A newspaper and magazine journalist, Kahn wrote 20 or so books, including the 1972 classic “The Boys of Summer” about his hometown Brooklyn Dodgers.

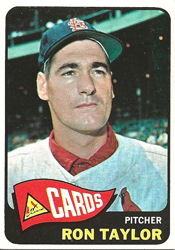

A newspaper and magazine journalist, Kahn wrote 20 or so books, including the 1972 classic “The Boys of Summer” about his hometown Brooklyn Dodgers. Acquired from the Indians on Dec. 15, 1962, the Toronto native was a prominent member of the Cardinals’ staff in 1964 when they won a World Series title.

Acquired from the Indians on Dec. 15, 1962, the Toronto native was a prominent member of the Cardinals’ staff in 1964 when they won a World Series title. A catcher who batted left-handed, Franks made his major-league debut with the Cardinals in 1939 as a backup to Mickey Owen.

A catcher who batted left-handed, Franks made his major-league debut with the Cardinals in 1939 as a backup to Mickey Owen.