The Cardinals wanted Joe Girardi to be their backup catcher but settled for Mike Matheny.

On Dec. 15, 1999, the Cardinals signed Matheny, a free agent, after failing in their bid to get Girardi, who went to the Cubs.

On Dec. 15, 1999, the Cardinals signed Matheny, a free agent, after failing in their bid to get Girardi, who went to the Cubs.

The Cardinals’ No. 2 choice turned out to be a No. 1 catcher.

Matheny became the Cardinals’ starter in 2000, helped them become division champions and won a Gold Glove Award for his defensive excellence. Matheny played five seasons for the Cardinals, who got to the postseason in four of those years, and won the Gold Glove Award three times.

In a nifty twist, Girardi became a free agent after the 2002 season and signed with the Cardinals to be Matheny’s backup in 2003.

Prayers answered

After five years (1994-98) with the Brewers, Matheny was a backup to Blue Jays catcher Darrin Fletcher in 1999 and hit .215 in 57 games.

“Matheny is an intelligent, studious catcher with a quiet motion behind the plate and an easy rapport with the pitchers,” The Sporting News noted, but his weak hitting was keeping him from being a starter.

“It’s a simple matter of the requisite bat speed being absent,” The Sporting News concluded in September 1999. “Barring a miraculous transformation at the plate, his destiny is to be a backup catcher.”

When Matheny, 29, became a free agent after the 1999 season, the Brewers showed interest, but not the Cardinals.

St. Louis general manager Walt Jocketty “thought he had a good chance to sign Joe Girardi,” the St. Louis Post-Dispatch reported.

Girardi was with the Yankees from 1996-99 and played in three World Series for them before becoming a free agent. Though the Cardinals offered more money than the Cubs did, he signed with Chicago to be near his home.

Pitcher Pat Hentgen, whom the Cardinals acquired from the Blue Jays in November 1999, urged them to sign Matheny.

The Cardinals gave Matheny a one-year deal for $750,000 and planned to have him back up incumbent starter Eli Marrero.

“I like to think I’m an unselfish player and will be helpful whether I’m playing or not,” Matheny said. “That doesn’t mean I’m not interested in playing, because I am.”

An Ohio native who attended the University of Michigan, Matheny was residing with his wife, Kristin, and four children in Weldon Spring, Mo., about 25 miles from St. Louis. Kristin grew up in the St. Louis suburb of Chesterfield and she and her husband had decided to raise their family in the area.

“She must have some powerful prayers because we really didn’t think about the Cardinals being interested in us,” Matheny told the Post-Dispatch.

Fighting for a job

A couple of weeks before spring training began in 2000, the Cardinals signed another free-agent catcher, Rick Wilkins, creating competition for Matheny. Wilkins had been in the big leagues for nine seasons (1991-99) and hit .303 with 30 home runs for the 1993 Cubs.

If Matheny didn’t hit, Wilkins gave the Cardinals an option.

“I wish I could take a little of the enthusiasm I feel when I’m behind the plate and have it when I get into the batter’s box,” Matheny told the Post-Dispatch. “I just love being behind the plate, all the strategy that goes unseen there, but I’m working on revamping my swing and improving on the things that have held my statistics back.”

The Cardinals entered spring training committed to Marrero, 26, as their starting catcher. Marrero, diagnosed with thyroid cancer in 1998, hit .192 in 114 games for the Cardinals in 1999, but management expected him to be stronger and better in 2000.

Initially, all three catchers struggled to hit in spring training. Two weeks before the season opener, their batting averages were .091 for Matheny, .100 for Marrero and .217 for Wilkins.

“I put a lot more pressure on myself early on than I should,” Matheny said. “I was trying to do too much and open eyes … Then I started to panic, trying to make up for lost ground.”

A hot streak near the end of spring training earned Matheny the backup job over Wilkins, who was sent to the minor leagues. Wilkins “was very much in the picture until Matheny had a stronger last week offensively,” the Post-Dispatch reported.

On March 29, 2000, manager Tony La Russa informed Matheny he was on the Opening Day roster. “It was like making the big leagues for the first time,” Matheny said.

Taking charge

When the Cardinals opened the season on April 3, 2000, at home against the Cubs, the starting catchers were Matheny and Girardi. With his father and brothers attending from Ohio, Matheny contributed a single and a double and scored a run in the Cardinals’ 7-1 triumph. Boxscore

Experiencing an Opening Day in St. Louis for the first time, Matheny said, “I can honestly say it was about the most fun I’ve ever had playing in the game.”

Hitting and fielding well and displaying a quick release on throws, Matheny supplanted Marrero as the No. 1 catcher. In May 2000, The Sporting News declared, “Matheny continues to exceed expectations.”

On July 1, 2000, Marrero tore a ligament in his left thumb. A couple of weeks later, Matheny cracked a rib but continued to play. He wore a flak jacket and had his chest taped before every game. Carlos Hernandez, acquired from the Padres at the trade deadline, gave the Cardinals insurance at the catcher position.

Matheny hit .261 with 47 RBI in 128 games for the 2000 Cardinals and led National League catchers in number of runners caught attempting to steal (49). He sat out the postseason after he severed two tendons and a nerve in his right ring finger while using a hunting knife he received as a 30th birthday gift.

After their playing careers, Girardi and Matheny became big-league managers. Girardi won a World Series championship with the 2009 Yankees and Matheny won a National League pennant with the 2013 Cardinals.

In 1937, Vanek was manager of the Cardinals’ farm club in Monessen, Pa., when he gave a tryout to Musial, 16, a prep player from nearby Donora, Pa. The Cardinals followed Vanek’s suggestion and signed the left-handed pitching prospect.

In 1937, Vanek was manager of the Cardinals’ farm club in Monessen, Pa., when he gave a tryout to Musial, 16, a prep player from nearby Donora, Pa. The Cardinals followed Vanek’s suggestion and signed the left-handed pitching prospect. On Dec. 10, 1979, the Cardinals traded pitcher Ray Searage to the Mets for Davis, a catcher.

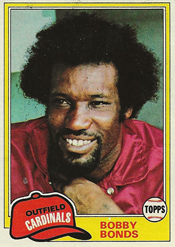

On Dec. 10, 1979, the Cardinals traded pitcher Ray Searage to the Mets for Davis, a catcher. On Dec. 7, 1979, the Cardinals acquired Bonds from the Indians for pitcher John Denny and outfielder Jerry Mumphrey.

On Dec. 7, 1979, the Cardinals acquired Bonds from the Indians for pitcher John Denny and outfielder Jerry Mumphrey. On Dec. 7, 2009, the Cardinals signed Penny, a free agent, and projected him to join a 2010 starting rotation with Chris Carpenter, Adam Wainwright, Kyle Lohse and Jaime Garcia.

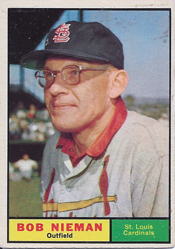

On Dec. 7, 2009, the Cardinals signed Penny, a free agent, and projected him to join a 2010 starting rotation with Chris Carpenter, Adam Wainwright, Kyle Lohse and Jaime Garcia. On Dec. 2, 1959, the Cardinals acquired Nieman from the Orioles for outfielder-catcher Gene Green, plus catcher Chuck Staniland.

On Dec. 2, 1959, the Cardinals acquired Nieman from the Orioles for outfielder-catcher Gene Green, plus catcher Chuck Staniland.