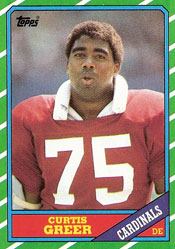

As an amateur pitcher, Ryan Kurosaki experienced a dramatic change in climate, landscape and culture, leaving the tropical paradise of Hawaii after high school and going to the prairies of Nebraska to attend college.

After making that transition, a leap from the minors at Arkansas to big-league St. Louis might seem feasible, but it turned out to be too much too soon.

Fifty years ago, in 1975, as a right-handed reliever with barely more than a year of professional experience, Kurosaki was called up to the Cardinals from Class AA Little Rock. After only a month with St. Louis, Kurosaki was sent back to Arkansas and never returned to the big leagues.

A pitcher whose job it was to put out fires, Kurosaki built a second career as a professional firefighter.

Aloha

A grandson of Japanese immigrants, Kurosaki developed an interest in baseball as a youth in Honolulu. In June 1962, when he was 9, Kurosaki was among a group of pee-wee players shown receiving instruction from Irv Noren, manager of the minor-league Hawaii Islanders, in a photo published in the Honolulu Star-Bulletin.

Kurosaki eventually became a standout pitcher for Kalani High School. As a senior in 1970, he helped Kalani win a state championship. Lenn Sakata, the club’s junior shortstop, recalled to the Honolulu Star-Advertiser that Kurosaki “was captain of our team. We looked up to him. He was the leader.”

(Sakata went on to play 11 seasons in the majors with the Brewers, Orioles, Athletics and Yankees.)

Dave Murakami, a Hawaiian who played baseball for the University of Nebraska in the 1950s, recommended Kurosaki to Cornhuskers head coach Tony Sharpe, who offered a scholarship. At Murakami’s urging, Kurosaki accepted.

Asked in May of his freshman year about making the adjustment from Hawaii to Nebraska, Kurosaki told the Omaha World-Herald, “It is a lot different … I still miss Hawaii. When you’re stuck in the snow, you get that way.”

Any feelings of homesickness didn’t prevent Kurosaki from developing into a reliable starter for Nebraska. Highlights during his three seasons there included shutouts of Kansas State, Oklahoma and Oklahoma State.

In the summers after his sophomore and junior seasons, Kurosaki pitched for a semipro team in Kansas managed by former big-league outfielder Bob Cerv. “That’s where I developed my slider,” Kurosaki told the Honolulu Star-Bulletin.

Pitching well in the National Baseball Congress Tournament, Kurosaki impressed Cardinals scouting supervisor Byron Humphrey. Opting to forgo his senior season at Nebraska, Kurosaki, 21, signed with the Cardinals in August 1973.

Fast rise

Assigned to Class A Modesto of the California League, Kurosaki had a splendid first season in the Cardinals’ system in 1974. Playing for manager Lee Thomas, Kurosaki was 7-3 with six saves. He struck out 74 in 71 innings and had a 2.28 ERA. “Ryan has a great slider and keeps the ball low,” Thomas told the Modesto Bee. “He’s everything you want in a relief pitcher.”

Promoted to Class AA Arkansas for his second pro season in 1975, Kurosaki baffled Texas League batters. In his first 11 relief appearances covering 21 innings, he didn’t allow an earned run and was 4-0 with four saves.

In May, the Cardinals demoted starter John Denny to Tulsa, moved reliever Elias Sosa into the rotation and brought up Kurosaki to take Sosa’s bullpen spot.

When Arkansas manager Roy Majtyka informed Kurosaki he was headed to the big leagues, the pitcher called his parents in Hawaii. “The family went crazy when I gave them the news,” Kurosaki told the St. Louis Post-Dispatch. “I still can’t believe I’m up here.”

As he recalled to the Honolulu Star-Advertiser, “I was in awe when I reported. My teammates included Lou Brock and Bob Gibson.”

The Cardinals assigned first baseman Ron Fairly, 36, to be the road roommate of Kurosaki, 22, and help him get acclimated. Kurosaki was 6 when Fairly debuted in the majors with the 1958 Dodgers.

Good start

When Kurosaki entered his first game for the Cardinals on May 20, 1975, at San Diego, he became the first American of full Japanese ancestry to play in the majors, the Honolulu Star-Advertiser reported.

(The first Japanese native to play in the big leagues was pitcher Masanori Murakami with the 1964 Giants. The first Asian-born player with the Cardinals was Japanese outfielder So Taguchi in 2002.)

Kurosaki’s debut was a good one. He worked 1.2 innings against the Padres, allowing no runs or hits. Boxscore

His next three outings _ one against the Dodgers (two innings, one run allowed) and two versus the Reds _ had many pluses, too.

On May 31 against the Reds, Kurosaki retired Johnny Bench, Dan Driessen, Cesar Geronimo and Dave Concepcion before giving up a solo home run to George Foster. Boxscore

The next day, Kurosaki held the Reds scoreless in two innings of work. He gave up two singles but retired Joe Morgan, Bench, Driessen, Concepcion, Foster and Jack Billingham. Morgan and Foster struck out. Boxscore

In four appearances for the Cardinals, Kurosaki had a 2.45 ERA.

Rough patch

After that, Kurosaki faltered. He allowed four runs in less than an inning against the Reds, gave up a three-run homer to Cliff Johnson of the Astros, and allowed three runs in 1.2 innings versus the Pirates. Relieving Bob Gibson (making his first relief appearance since 1965) at Pittsburgh, Kurosaki gave up singles to pitcher Bruce Kison and Rennie Stennett. Kison stole third and scored on Kurosaki’s balk. (Cardinals manager Red Schoendienst got ejected for contesting the balk call.) Boxscore

Kurosaki was sent back to Arkansas. Little did he know his big-league days were over. His totals in seven appearances for the Cardinals: 7.62 ERA, with 15 hits allowed, including three home runs, in 13 innings.

“I think they might have brought me up a little too quick,” Kurosaki said to the Omaha World-Herald. “It’s tough on you mentally when you’re somewhere you know you don’t belong. I knew that I didn’t belong in St. Louis. I knew that I wasn’t pitching for them the way I knew I could pitch.”

Reflecting on Kurosaki’s stint with St. Louis, former American League umpire Bill Valentine, who became Arkansas general manager in 1976, told 501 Life Magazine of Conway, Ark., “It was one of the silliest things the Cardinals ever did … No way he could be ready.”

Getting sent back to Little Rock did have one significant benefit for Kurosaki: He met Sandra McGee there in 1975 and they married in 1978.

Sounding the alarm

Based on his work at Arkansas, it was reasonable to think Kurosaki would be heading back to St. Louis at some point. He was 7-2 with seven saves and a 2.03 ERA for Arkansas in 1975; 5-2 with six saves and a 3.25 ERA in 1976.

After two good seasons at Class AA, Kurosaki expected a promotion to Class AAA in 1977 but instead the Cardinals sent him back to Arkansas. Once again, he delivered, with 14 saves and five wins.

So it was tough for Kurosaki to take when the Cardinals told him to report to Arkansas for a fourth consecutive season in 1978.

“Same old story year after year,” Kurosaki told the Omaha World-Herald. “They told me I could go to the Mexican League, but I said I wouldn’t go. I asked them to trade me, but they wouldn’t. They told me it was either the Mexican League or Little Rock. It is getting to the point where I’m thinking that if the Cardinals don’t have any plans for me, perhaps it would be better if I went somewhere else.”

The Cardinals wanted Kurosaki to develop a screwball or forkball to go with his slider and sinker, The Sporting News and Honolulu Star-Bulletin reported.

Kurosaki, 26, earned 11 saves for 1978 Arkansas and finally got a mid-season promotion _ to Springfield, Ill., where he was 5-2 with three saves and a 2.40 ERA for the Class AAA club.

A second chance at the majors, though, wasn’t offered. As Bill Valentine suggested to 501 Life Magazine, the Cardinals “forgot about him.”

Kurosaki spent two more years in the minors, then was finished playing pro baseball at 28.

In 1982, after a year with the Benton (Ark.) Fire Department, Kurosaki began a 32-year career with the Little Rock Fire Department, retiring as a captain in 2014.