Known for their rowdy behavior, the Gashouse Gang Cardinals had the tables turned on them during an exhibition at Bridgeport, Connecticut, in June 1935.

Confronted by spectators who stormed the field “snatching caps, gloves and even trying to hold the players while attempts were made to steal their shoes from their feet,” the reigning World Series champions “were thankful to escape with their lives,” the St. Louis Post-Dispatch reported.

Confronted by spectators who stormed the field “snatching caps, gloves and even trying to hold the players while attempts were made to steal their shoes from their feet,” the reigning World Series champions “were thankful to escape with their lives,” the St. Louis Post-Dispatch reported.

Featuring the likes of Dizzy Dean, Leo Durocher, Pepper Martin and Joe Medwick, the Gashouse Gang Cardinals were a cocky bunch. In Bridgeport, though, the club staggered, not swaggered, out of town.

Coming to Connecticut

Though the Cardinals became World Series champions with a colorful cast of characters in 1934, the Great Depression took a toll on revenue. Sharing Sportsman’s Park with the American League Browns, the 1934 Cardinals drew a mere 334,863 to their home games. After the World Series, club owner Sam Breadon considered selling the Cardinals to an Oklahoma oilman, Lew Wentz, or relocating the franchise to Detroit.

Eager for a buck, Breadon agreed to have the 1935 Cardinals stop in Bridgeport on their way to Boston and play an exhibition game against a semipro team. Bridgeport appealed to Breadon because game organizers offered him a guaranteed amount from ticket sales. Another incentive was the Bridgeport ballpark. It had lights, a novelty for the Cardinals. (On May 24, 1935, three weeks before the Cardinals went to Bridgeport, the first night game in the majors was played at Cincinnati.)

As Tim Wiles of the Baseball Hall of Fame noted, “Night baseball … did much to reinvigorate attendance, helping draw fans out into the cooler night air in the days before home air conditioning was widespread … An aura of gimmickry seemed to some to be part and parcel of the night baseball experience.”

After completing a series at home against the Cubs, the Cardinals arrived by train in Bridgeport on Monday, June 10, for their exhibition that night.

(Twenty-four years earlier, in 1911, a train carrying the Cardinals derailed in Bridgeport. Fourteen people were killed. The Cardinals escaped injury and helped in rescue efforts.)

Located on the Long Island Sound, Bridgeport was an industrial center. In 1875, its mayor was the greatest showman, P.T. Barnum, founder of Barnum & Bailey Circus. Notable Bridgeport natives include actor Robert Mitchum, playwright and gay rights activist Larry Kramer, and singer/guitarist John Mayer.

Bridgeport also has a rich baseball history. Big-league players born there include pitchers Rob Dibble, a “Nasty Boy” reliever for the 1990 World Series champion Reds; Kurt Kepshire, starter for the 1985 National League champion Cardinals; and Charles Nagy, starter on two American League pennant winners for Cleveland.

The first professional team in Bridgeport played in the Eastern League in 1885. When the league folded in 1932, Bridgeport was without a minor-league club, but industries there stocked several strong semipro teams. That’s why the Cardinals had a semipro opponent, the Automotive Twins, for their June 1935 exhibition.

Assault and battery

Pitchers Jesse Haines and Phil Collins, who were scheduled to start the next two regular-season games, and first baseman Rip Collins, who didn’t feel well, were sent ahead to Boston. The rest of the Cardinals got off the train in Bridgeport.

Trouble brewed from the outset. There were disputes about the gate receipts and “for a time it seemed that the Cardinals would have to depart without a game or their guarantee,” the Post-Dispatch reported. Eventually, though, the matter was settled, but the game didn’t begin until 9 p.m. According to the Associated Press, 3,500 people attended “in spite of threatening weather.”

When the Cardinals were in the field, spectators climbed out of the stands and swiped caps, shoes, sweatshirts, sweaters, gloves and bats, the Post-Dispatch reported. Some were wildly bold and aggressive.

According to reporter J. Roy Stockton, Terry Moore “was mobbed in center field by a group trying to get his cap. When he resisted, he was tripped, and the hoodlums tried to take off his shoes. A well-directed kick gave him a chance to escape. (Later), while he was chasing a fly ball, his cap was snatched from his head.”

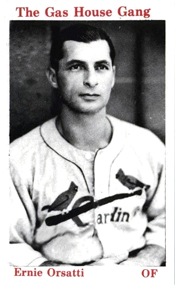

Others surrounded Cardinals outfielder Ernie Orsatti. “When he resisted, he was pummeled, thrown to the ground and walked upon,” the Post-Dispatch reported.

All the baseballs were stolen, except one. “There were long delays while it was being retrieved after being hit to the outfield or to foul territory,” according to the Post-Dispatch.

By mutual agreement, the game was halted after eight innings. The Cardinals won, 9-4. Rookie pitcher Ray Harrell went the distance for St. Louis. Ernie Orsatti had three hits and Joe Medwick contributed a pair of doubles.

When the game ended, the Cardinals “had to take bats in hand to protect their remaining equipment as they retreated to taxicabs,” the Post-Dispatch reported. “Charlie Wilson (a third baseman) twice was dragged from a taxicab by a group of hoodlums seeking souvenirs and had to fight his way out of the mob.”

The headline in the next day’s Post-Dispatch declared: “Cardinals Pummeled By Hoodlums; Robbed Of Caps, Gloves.”

Recovery time

In Boston on Tuesday, June 11, rain postponed the Cardinals’ game against the Braves. As the Post-Dispatch noted, St. Louis players “welcomed the day of rest after their experience at Bridgeport.”

Some of the Cardinals spent the unexpected off day at Rockingham Park, the thoroughbred horse racing track in Salem, New Hampshire. “Some of the lads got the price of a new suit, and some will wear the old jeans for some time to come,” the Boston Globe reported.

In his syndicated newspaper column, Dizzy Dean wrote, “One thing the rain does is give the ballplayers a chance to go sightseeing. Boston is a great place for that (and) you can’t beat them steamed clams.”

Returning to the field on Wednesday, June 12, the Cardinals swept a doubleheader from the Braves _ and didn’t get mugged by anyone at the ballpark. Boxscore and Boxscore

Trouble seemed to follow the gas house gang wherever they went. With the way MLB brings in billions and the way they just print up money it’s hard to imagine how tough things were during the depression. Couldn’t they afford any police or security guards to keep the fans off the field? Reminds me of the way fans would just storm the field after winning a World Series during the 70’s and 80’s.

Printing money is an apt way to describe professional and big-time college sports today, Phillip. Thanks for your comments.

A country that is slashing funding of social services, medical care, education resources and environmental safeguards is spending billions on sports entertainment. Perhaps when (if) that trend is ever reversed, the country really will start to be great again.

The St. Louis Cardinals have exceeded $300 million in yearly revenue each year since 2015 (with the exception of the pandemic year of 2020). In 2024, the Cardinals’ revenue was $373 million, according to Forbes. There is no incentive for the franchise to win World Series championships (or pay the crazy costs necessary for that), because the revenue flows in, even when the team is mediocre.

Sounds like a horror movie. I’m reminded of Chris Chambliss trying to get off the Yankee Stadium Field after hitting a game winning homer in the playoffs. Why can’t fans run on the field and just celebrate instead of stealing player hats and mauling them. Mob mentality s a dangerous aspect of society.

Agree with your comment on mob mentality, Steve.

In 2024 Reuters news service reported, “Fan violence has made workplace safety a growing concern for footballers (soccer players), who are having to deal with flares and missiles being hurled from the stands, pitch invaders and verbally abusive supporters, an International Federation of Professional Footballers report said.

The global players union said the footballers, or soccer players, complained they often had to accept the aggression in silence rather than talk about it for fear it might exacerbate the abuse or impact their job opportunities.

I’d imagine you are one of about (and I’m totally pulling this figure out of my ass) 50 people on planet Earth who is an expert on “The Gashouse Gang” Imagine that! That’s a cool place to be and I love stuff like that.

Thanks, Gary. It’s interesting that no big-league team folded because of financial hardship during the Great Depression. If nothing else, the Gashouse Gang, and their antics, created an entertaining diversion for the many people who were struggling to make ends meet then.

In the late-60s, early 70s, not too long after the Astrodome was built, Houston was having a good first-half season, and someone referred to the Astros as “The Glasshouse Gang;” Harry Walker or Leo Durocher was the manager.

Good stuff. Thanks. You know your baseball.

On July 11, 1972, when the Astros were 45-33, one game behind the division-leading Reds, Joe Heiling of the Houston Post referred to the club as the Glasshouse Gang. Manager Harry Walker told the newspaper, “From a club that was not respectable, we’ve become a club that other teams know they are going to have a tough battle on their hands when they play us.”

The Astros faded and Walker was replaced by Leo Durocher the following month. Heiling continued to refer to the Astros as the Glasshouse Gang while Durocher managed the club in 1973. One of those instances came after the Astros beat the Dodgers, 3-2, on July 31, 1973, despite being limited to four hits. Houston third baseman Doug Rader told the Post, “We played the game right tonight. We got runners over when we had to and we got guys in with one out. It’s fun to play a game like this.”