Mickey Lolich was at a crossroads in his pitching career when a former Cardinals ace came to his rescue.

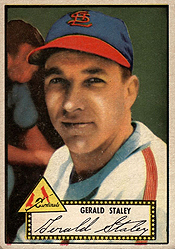

A left-hander with a stellar fastball he couldn’t control, Lolich, 21, was an unhappy prospect in the Tigers system when he was dispatched to Portland (Ore.) in 1962. The pitching coach there, Gerry Staley, 41, served a dual role as reliever.

A left-hander with a stellar fastball he couldn’t control, Lolich, 21, was an unhappy prospect in the Tigers system when he was dispatched to Portland (Ore.) in 1962. The pitching coach there, Gerry Staley, 41, served a dual role as reliever.

Staley had been a big winner for the Cardinals before becoming a closer for the White Sox. Perhaps his biggest save came later with the work he did on Lolich. Staley taught him how to make a fastball sink. Lolich became a pitcher instead of a thrower, a winner instead of a loser. The sinkerball made all the difference.

Six years later, Lolich earned the 1968 World Series Most Valuable Player Award for beating the Cardinals three times, including in the decisive Game 7.

In his 2018 book “Joy in Tigertown,” Lolich suggested Staley deserved a 1968 World Series share for helping him become a success. “Meeting him was one of the great breaks of my career,” Lolich said. “Maybe the most important one.”

Wild thing

Two-year-old Mickey Lolich was pedaling a tricycle as fast as he could in his Portland (Ore.) neighborhood when he lost control and slammed into the kickstand of a parked motorcycle. The big bike crashed down on the tyke, pinning him to the ground. His left collarbone was fractured.

“Well, back in 1942, they just sort of strapped your arm across your chest and waited for it to heal,” Lolich recalled to Pat Batcheller of Detroit Public Radio (WDET, 101.9 FM) in 2018. “When they took the bindings off, I had total atrophy in my left arm. It wasn’t working at all.”

Though Mickey was right-handed, a doctor advised the Lolich family to encourage him to use his left hand and arm as much as possible to build strength. His parents “tied my right arm behind my back and made me use my left hand,” Lolich told Detroit Public Radio. “I wanted to throw those little cars and trucks, so I threw them left-handed … and that’s how I became a left-handed pitcher.”

The kid learned to throw with velocity, too. In his senior high school season, Lolich struck out 71 in 42 innings. He was 17 when the Tigers signed him in 1958 and told him to report to training camp the following spring.

Lolich’s first manager in the minors was fellow Portland native Johnny Pesky, the former Red Sox shortstop whose late throw to the plate enabled Enos Slaughter to score the winning run for the Cardinals in Game 7 of the 1946 World Series.

When Braves executive Birdie Tebbetts saw Lolich’s fastball in April 1959, he told Marvin West of the Knoxville News-Sentinel, “I’d give cold cash for this Lolich boy.”

The problem was control. In a four-hit shutout of Asheville in May 1959, Lolich walked nine but was bailed out by five double plays. A month later, in a two-hitter to beat Macon, he walked 11 and threw four wild pitches.

Lolich began each of his first three pro seasons (1959-61) with Class A Knoxville and was demoted to Class B Durham each year. In June 1961, after Lolich gave up no hits but nine walks and four runs in a five-inning start, Knoxville manager Frank Carswell told the News-Sentinel, “I’ve seen some strange games, but I can’t remember seeing one pitcher give away a decision without a hit.”

Headed home

After a strong spring training in 1962, Lolich was assigned to Class AAA Denver, but he was a bust (0-4, 16.50 ERA). In late May, the Tigers demoted him to Knoxville, but Lolich refused to return there. Instead, he went home to Portland. The Tigers suspended him.

Portland had a city league for amateur and semipro players in conjunction with the American Amateur Baseball Congress. Lolich showed up one night in the uniform of Archer Blower, a maker of industrial fans, faced 12 batters and struck out all of them, the Oregon Daily Journal reported.

Blown away by the performance, the Tigers quickly reinstated Lolich and arranged for him to pitch the rest of the summer for the Portland Beavers, the Class AAA club of the Kansas City Athletics. That’s when Gerry Staley got a look at him. In the book “Summer of ’68,” Lolich told author Tim Wendel, “He (Staley) asked if I’d give him 10 days to let him try and turn me into a pitcher. All I was then was a thrower, really. I’d stand out there and throw it as hard as I could.”

Lolich agreed to the proposal.

Starting and closing

Gerry Staley went from Brush Prairie, his rural hometown in Washington state, into pro baseball as a rawboned right-handed pitcher who “looks as if he could whip a wounded bear,” Dwight Chapin of the Vancouver Columbian noted.

When he was with a Cardinals farm club in 1947, Staley was throwing warmup tosses to infielder Julius Schoendienst, brother of St. Louis second baseman Red Schoendienst. “He noticed I had a natural sinker when I threw three-quarters overhand,” Staley recalled to United Press International. “He said my sinker did more than my fastball. So I stuck with it.”

When he was with a Cardinals farm club in 1947, Staley was throwing warmup tosses to infielder Julius Schoendienst, brother of St. Louis second baseman Red Schoendienst. “He noticed I had a natural sinker when I threw three-quarters overhand,” Staley recalled to United Press International. “He said my sinker did more than my fastball. So I stuck with it.”

Using the sinker seven out of every 10 pitches, Staley became a prominent starter with the Cardinals. He had five consecutive double-digit win seasons (1949-53) for St. Louis. His win totals included 19 in 1951, 17 in 1952 and 18 in 1953.

In explaining to Al Crombie of the Vancouver Columbian how he threw the sinker, Staley said, “You have to release the ball off one finger more than the other, and then I roll my wrist to get a little more of the downspin on the ball.”

Staley threw a heavy sinker. According to the Vancouver newspaper, “It breaks down at the last second, and as the surprised hitter gets his bat around on it, most of the ball isn’t there. Most of the time it dribbles off harmlessly to an infielder and is made to order for starting double plays.”

Traded to the Reds in December 1954, Staley went on to the Yankees and then the White Sox, who made him a reliever. In 1959, Staley got the save in the win that clinched for the White Sox their first American League pennant in 40 years. He appeared in 67 games that season and had eight wins, 15 saves and a 2.24 ERA. The next year also was stellar for him (13 wins, nine saves. 2.42 ERA).

Released by the Tigers in October 1961, Staley snared an offer to coach and pitch for Portland.

Soaring with a sinker

Mickey Lolich became Staley’s star pupil. As author Tim Wendel noted, “After a week or so, Lolich caught on to what Staley was trying to teach him _ how it was better to be a sinkerball pitcher, with control, than a kid trying to throw 100 mph on every pitch. The new goal was to keep the ball low, often away from the hitter, consistently hitting the outside corner.”

Staley also taught Lolich to extend his pregame warmup time. The extra pitches tired his arm a bit and gave more sink to his sinker.

The results were impressive. In 130 innings for Portland, Lolich struck out 138 and yielded 116 hits. The next year, he reached the majors with Detroit. “Gerry Staley changed my whole life,” Lolich told Tim Wendel. “It’s as simple as that.”

In the 1968 World Series, Lolich won Games 2, 5 and 7. He went the route in all three, posting a 1.67 ERA.

Lolich had double-digit wins 12 years in a row (1964-75), including 25 in 1971 and 22 in 1972. He pitched more than 300 innings in a season four consecutive times (1971-74).

In 16 seasons in the majors with the Tigers (1963-75), Mets (1976) and Padres (1978-79), Lolich earned 217 wins and had 41 shutouts. He is the Tigers’ career leader in strikeouts (2,679), starts (459) and shutouts (39).

The 1962 season with Portland was Gerry Staley’s last in professional baseball. He became superintendent of the Clark County (Washington) Parks Department. “It was time I went to work,” he told the Vancouver Columbian.

After retiring in 1982, Staley enjoyed gardening and fishing for steelhead trout. Once a week, he would take time to carefully autograph items mailed to him by baseball fans. “There are some people who won’t sign unless they get paid for it,” Staley said to the Vancouver newspaper. “What the heck. I’ve got enough to live on. It’s nice to be remembered.”

A remarkable tale. Add another three game winner in a World Series. I didn’t know that about Lolich and how fascinating to learn of his injury as a two year old and switch to being left-handed. I appreciate Lolich’s recognition of how much Staley meant to him, saying that he deserved a 1968 World Series share of the pot and how he transformed his approach to pitching.

I know I’ve had many guides over the years and I let them know without putting them too high on a pedestal, but they sure do deserve credit. I don’t know where I’d be without them?

Last point, a refreshing one, to read about pitchers and their success without trying to overpower every batter with 100 mph fastballs. It gets boring. Give me a Cuellar or a Lolich any day over a flame thrower.

I appreciate your keen observations, Steve. I’m especially glad for your wisdom about mentors and their impact on lives.

As you note, pitching is about much more than velocity. As a sinkerball specialist, Gerry Staley in retirement became a fan of Bruce Sutter and his split-fingered pitch. In 1982, after watching on TV as Sutter helped the Cardinals become World Series champions, Staley said to Al Crombie of the Vancouver Columbian, “It’s a real good sinker … He’s got everyone coming up to the plate thinking sinker … and that makes his slider and fastball that much more effective. He throws that sinker with a lot of different speeds. That makes it tough, too.”

i’ve recently started to ask people once i get to know them a little if they’ve ever been so impressed by someone that they would refer to them as a mentor or a guide and so far, they’ve said no….just four people, small sample size, but my mind leaps to thinking that if there is reincarnation, then these four are on their last life. they’ve served their time and I say this because in my life i continuously have guides so i figure i’m new to all of this.

I had no idea about the childhood injury nor the way Gerry Staley saved his career. It hurts me to say this but Micky Lolich made the Cardinals hitters look bad. While there certainly was some controversy in regards to game 5, in games 2 and 7 the Cardinals mustered only 11 hits in 62 at bats against Lolich. Only one of those hits went for extra bases. Let’s not also forget that in the 6th inning of that fateful game 7 Micky Lolich picked off both Lou Brock and Curt Flood. He actually went into that World Series on a hot streak. After having a record of 7-7 through July he went 10-2 during August and September with an era of 1.94. In 1971 with a little bit of luck he might have won 30 games. Of his 14 losses 9 were by one run. Micky Lolich was indeed a pitcher from another time when pitchers were a lot more than just 100mph fastballs and 5 inning quality starts. Thanks for another fine post Mark. And a Happy New Year to everyone.

Happy new year to you, Phillip. May 2026 bring peace and justice to all.

Thanks for the good insights you provided on Mickey Lolich. Asked his approach to pitching against the 1968 Cardinals, Lolich told the Detroit Free Press, “Keep the ball down, throw strikes, duck and pray.”

In addition to his three complete-game wins in the World Series, Lolich hit a home run against Nelson Briles in Game 2 at St. Louis. It was a stunner. In 821 regular-season career at-bats in the majors, Lolich never hit a homer. Against Briles, he tomahawked a high fastball over the wall in left at Busch Memorial Stadium. “I was shocked,” Lolich told the Free Press. “I never hit a home run in professional baseball in my life … I was shocked I hit the ball to left, too. I never pull the ball.” https://www.retrosheet.org/boxesetc/1968/B10030SLN1968.htm

Appreciate a story that concludes with a man choosing kindness over greed.

Yes, indeed, Ken. And thanks for reading all the way through to the end.

I remember before the 1968 World Series, Roger Mari’s warned his Cardinal teammates that they had more to worry about facing Mickey Lolich than with 30 game winner Denny McLain.

Good stuff, Richard. During his days in the American League, Roger Maris batted .190 (4-for-21) versus Mickey Lolich, with one home run (a two-run shot in 1963 at Yankee Stadium).

In the book “Roger Maris: Baseball’s Reluctant Hero,” by Tom Clavin and Danny Peary, Cardinals shortstop Dal Maxvill said, “All our players were talking about McLain, and Roger said, ‘I’ll tell you something, guys. McLain is not the guy we’ve got to worry about here. We need to worry about the other guy _ Mickey Lolich.’ And we all looked around and said, ‘Oh, yeah? Mickey Lolich?’ “

lol, Maris knew what he was talking about!

It’s highly classy for people to recognize the men and women who keyed their success. Lolich was sensational in the WS of 1968. STL would not win another WS game until 1982, and I was there, thanks to my good friend Bob Burnes, the Benchwarmer of The Globe-Democrat. He somehow arranged for us Globe employees to buy tix for the playoffs and WS. It was a huge hassle for him.

Gerry Staley was a favorite of my ol’ man. He said he and his brother in law, Uncle Russ, went to a game in the early 1950s that was supposed to be a pitchers’ duel. Staley for STL, Preacher Roe for Brooklyn. HA! more than 20 runs later, my dad was thrilled with the game.

In 1979, I was at a STL/Padres game and saw one of Mickey’s last MLB appearances. I walked to the box seats and saw he was overweight and not throwing well. I just looked at him and remembered his dominance 11 seasons previously.

I see he is 85. Hang in there, “Tiger.”

Thank you for sharing those experiences with us.

Those 1950s Brooklyn Dodgers gave a lot of good pitchers trouble and Gerry Staley was one of them. His career record against Brooklyn was 10-19. Some of the career batting averages against Staley among top Brooklyn players included: Jackie Robinson, .432; Junior Gilliam, .413; Roy Campanella, .325; and Duke Snider, .318.

Gil Hodges, who hit seven regular-season career home runs against Staley, told Newsday, “There’s hardly anybody I’ve met in baseball that I disliked. Gerry Staley, he’s one. He’d knock me down in spring training.”

Before Mickey Lolich finished with the Padres, he did have a last hurrah against the Cardinals while with the 1976 Mets. On June 29, 1976, Lolich pitched a three-hit shutout versus the Cardinals at Shea Stadium: https://www.retrosheet.org/boxesetc/1976/B06290NYN1976.htm

Nice profile. It’s always good to learn of the connections many of the players have to one another or to an influential coach. In addition to winning three games in the ’68 Series, Lolich also hit the only homer of his career in Game 2.

Thanks much. That home run in Game 2 of the World Series was the only homer of Mickey Lolich’s big-league career. He hit none in 821 regular-season career at-bats.

Batting right-handed, Lolich hit the homer to left against right-hander Nelson Briles.

Two years later, Lolich taught himself to be a switch-hitter. In April 1970, he told Jim Hawkins of the Detroit Free Press, “I was so afraid of getting hit with the pitch when I’d have to bat right-handed against a right-hander, I was worthless at the plate, an automatic out. So this spring I worked on hitting left-handed … Now at least I can stand up against right-handers and swing the bat because I’m not afraid all the time.”

Here’s a clip of the Lolich World Series home run: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=YqPwNKc-ib0

the honesty, sincerity, the no bs….so refreshing.

I had heard about Lolich’s injury as a child that caused him to learn to throw as a lefty. I did not remember him becoming a switch-hitter. Thanks to the link to the World Series homer; it wasn’t a cheap one. And I loved seeing Gates Brown in the dugout after Lolich circled the bases. Home run trots and celebrations were much more reserved–and dignified–back then. That was a homer by a pitcher in the World Series. These days, if a guy gets a broken-bat flare single to right field, he celebrates like he just hit a game-winning homer in the World Series against the ’27 Yankees.

According to the St. Louis Post-Dispatch, as Mickey Lolich advanced toward first base, he was concentrating so hard on watching to see whether left fielder Lou Brock could make a play on the ball that he missed the bag and had to retrace his steps to touch first base before continuing on his trot.

My development as a lefty was not nearly as dramatic – or forced! I recall that 68 Series – he was amazing. I totally forgot he hit a homer in it…and it was his only one…against Briles of all people. Great post, Mark. Happy New Year!

Wishing you an abundance of happiness and humor in 2026, Bruce.

I imagine you were the proverbial crafty southpaw…

After his pitching career, Mickey Lolich owned and operated a doughnut shop in Michigan. (First, in Rochester, then Lake Orion and Washington Township.) As the Detroit Free Press noted, “For years, you could enjoy a doughnut made personally by a three-time all-star pitcher.”

“I didn’t want to be just a name on the front door,” Lolich told the newspaper. “So I put on my jeans and apron and learned the recipes.”

According to the Free Press, “When an employee calls in sick, Mickey is the one who works the midnight shift.”

Asked why he got into the doughnut business, Lolich replied to the Free Press, “I’ve done other work during the (baseball) off-seasons _ once I was a tennis club general manager, once I was a snowmobile salesman, so I figured I could sell doughnuts.”

In addition to a variety of doughnuts, Lolich’s shop offered maple bars, buttermilk sticks, cinnamon twists, crullers with colored sprinkles _ and lots of coffee.