Before Grover Cleveland Alexander or Dizzy Dean or Bob Gibson, the St. Louis pitcher who enthralled the hometown fans was Rube Waddell.

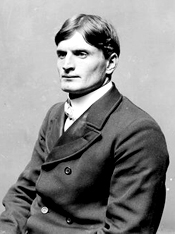

United Press described the eccentric left-hander as “the Peter Pan of the game, a boy who never grew up.”

Waddell had his prime (1902-07) with the Philadelphia Athletics, winning 131 and leading the American League in strikeouts each year. He spent his last three big-league seasons with the St. Louis Browns.

Facing his former team, Waddell struck out 16 Athletics, then an AL single-game record. As an encore, he dueled for 10 innings with Walter Johnson and fanned 17 Washington Senators.

A natural

George Edward Waddell was from Bradford, Pa., near the New York state border. The town is closer to Buffalo (78 miles) than it is to Pittsburgh (154 miles).

According to the Baseball Hall of Fame, Waddell got the nickname Rube because “he was a big, fresh kid.”

He was a stud, too. A “magnificent physique,” Tigers manager Hughie Jennings told the Detroit Free Press.

According to Harry Grayson of Newspaper Enterprise Association, “Rube’s hand wrapped itself around a baseball as though it were a marble.”

John Wray of the St. Louis Post-Dispatch wrote, “He had an arm like Hercules.”

Waddell used those physical gifts to pitch with velocity and movement. His fastball was exceptional, and he also spun an assortment of curves, drops and shoots.

At 20, Waddell got to the majors with Louisville of the National League in 1897, becoming a teammate of fellow rookie Honus Wagner. He went on to pitch for Pittsburgh and Chicago in the National League and had stints in the minors, including at Milwaukee, where Connie Mack was manager.

In 1901, Mack took over the Athletics and acquired Waddell a year later.

Special stuff

With the A’s, Waddell had 21 wins or more in four consecutive seasons (1902-05) and topped 300 strikeouts two years in a row (1903-04). No other pitcher had consecutive 300-strikeout seasons until Sandy Koufax (1965-66). In a July 1902 shutout of Baltimore, Waddell became the first American League pitcher to strike out the side on nine pitches, according to the Baseball Hall of Fame. Boxscore

The A’s were American League champions in 1902 and 1905. The pennants “were won mainly through the efforts of the Rube,” Mack told the Philadelphia Inquirer.

Waddell won 24 for the 1902 A’s after joining them in June. In 1905, he was the American League leader in wins (27), ERA (1.48) and strikeouts (287). In a July 4, 1905, doubleheader at Boston, Waddell won in relief in Game 1, then started Game 2 against Cy Young. It lasted 20 innings. Both starters went the distance, with Waddell prevailing. After the last out, he turned cartwheels from the mound to the dugout. “Rube Waddell was the best left-hander of all time,” Cy Young said in 1943, according to the Baseball Hall of Fame. Boxscore and Boxscore

Nap Lajoie, a five-time American League batting champion who totaled 3,243 hits, said of Waddell to the Cleveland Plain Dealer, “I never faced a better southpaw … I believe he had more speed than any other left-hander I ever batted against.”

Generous heart

Waddell was kindly, carefree, foolhardy, gullible and an inveterate carouser.

“He was entirely without inhibitions, and he acted on any impulse,” baseball author Mac Davis wrote in the Inquirer. “He disappeared for days to go fishing. Often he vanished in the middle of a game to chase fire engines, march in town parades or play marbles with children.”

Columnist Harry Grayson noted, “Waddell loved to pitch, but baseball rated fifth on his list of passions. Ahead of the game, in the order named, came fishing, drinking, tending bar and running to fires, with or without a fireman’s hat.”

Waddell’s “greatest delight was to assist in fighting fires,” the St. Louis Star-Times reported. “When not playing baseball, he loitered about fire engine houses and was always one of the first to find a seat in the hose van or to climb onto the engine when an alarm sounded.”

When the A’s had a day off in Washington, Connie Mack and a friend heard bells as fire engines raced to answer an alarm. “We pulled up in front of the building and I couldn’t help but admire the bravery of one fireman who perched on the window of the second story and poured water into the flames from a hose,” Mack said to Arthur Daley of the New York Times. “I watched him for a while, looked a little closer and, by golly, it was Rube Waddell.”

Waddell wrestled an alligator during spring training in Florida and was bitten on the hand while clowning with a circus lion in Chicago.

One of his favorite stunts was to enter a saloon flourishing a baseball and touting it as the one used in the 20-inning win against Cy Young. “It was a different ball every occasion,” Mack told Arthur Daley, “but it always was good for a few drinks.”

Having cashed a paycheck, Waddell liked to visit a saloon, buy drinks for himself and rounds for the house until his pockets were empty, then go behind the bar, don an apron and serve customers, the St. Louis Globe-Democrat reported.

Waddell likely was an alcoholic. According to the Globe-Democrat, “He had been known to consume a quart of whiskey before breakfast.”

According to The Sporting News, “Friends and admirers kept him full of alcohol from morning until night.”

Connie Mack told Arthur Daley, “I often had him arrested for his own good.”

As Hughie Jennings, the Tigers’ manager, noted to the Detroit Free Press, “If he hadn’t possessed superhuman strength and a constitution of iron, he wouldn’t have lasted as long as he did.”

Money meant little to Waddell. He spent it, or gave it away, as soon as he got some. Browns owner Robert Hedges resorted to doling out a dollar or so at a time to Waddell rather than pay his salary in lump sums. “Waddell hardly knew from one year to the other what his salary was,” The Sporting News noted. “The club paid his board bills and gave him a daily allowance of spending money, $1 or $2.”

The top salary Waddell got was $3,000. According to the Globe-Democrat, “Waddell had no realization of the value of money and was always so deeply in debt and so greatly in need of funds that he was willing to sign for any salary offered him provided he could get a few dollars in advance when he needed.”

While acknowledging that Waddell “was his own worst enemy,” Connie Mack told the Inquirer, “He was the best-hearted man on our team … When a comrade was sick, Rube was the first one on hand to see him and the last to leave. If he had money, it went for some gift or offering to the sick man.”

In a game at Boston on July 1, 1904, a Jesse Tannehill fastball hit A’s batter Danny Hoffman just above the eye. Hoffman fell to the ground in a heap. According to the Post-Dispatch, “Rube was the first man to his side. He lifted the unconscious player from the ground in his powerful arms as though Hoffman were a mere boy and carried him from the field … He spent the entire night by the (hospital) bedside of Hoffman.” Boxscore

Bound for Browns

Connie Mack was Waddell’s most ardent supporter but even he lost patience with the pitcher. In February 1908, the A’s sold Waddell’s contract to the Browns for $5,000. “Carousing with his Philadelphia friends caused Waddell to be (dealt),” the St. Louis Star-Times reported.

Waddell, 31, still was a top pitcher. He’d won 19 with a 2.15 ERA for the 1907 A’s.

In going to St. Louis, Waddell was reunited with his former A’s teammate, Danny Hoffman, who recovered from the beaning in Boston and joined the Browns.

On April 17, 1908, Waddell made his Browns debut in a start against the White Sox at Chicago and pitched a one-hit shutout in a 1-0 victory. Boxscore

A week later, in the Browns’ home opener, Waddell beat the White Sox again, with a four-hitter. Boxscore

The first time Waddell faced the A’s he beat them with a five-hitter at Philadelphia. Boxscore

A record and a comeback

On July 29, 1908, the A’s were in St. Louis and, oh, how the tables had turned. The Browns (53-38) were in second place, seven games ahead of the A’s (44-43), and Waddell again was starting versus his former club.

The A’s looked helpless early on, striking out often. The Browns led, 1-0, through five innings, but they encountered trouble in the sixth.

The umpire, 5-foot-7 Tommy Connolly, had his view of the plate obscured by Browns catcher Tubby Spencer. The first two A’s batters in the sixth drew walks. “Possibly Rube’s curves were too sharp for Little Tom standing behind Big (Tubby) Spencer,” the Post-Dispatch reported. “Connolly looks like a midget. He has to peek around, or under, (Tubby’s) arms to see the ball coming.”

The rejuvenated A’s scored three times in the sixth. Then, in the seventh, Waddell zoned out. With a runner on third and two outs, Eddie Collins topped a grounder to first baseman Tom Jones, who moved in, gloved the ball and turned, looking for Waddell to take the toss at first. Waddell, however, stood frozen on the mound as the runner from third streaked home, extending the A’s lead to 4-1.

Trying to cover his gaffe, Waddell dropped to one knee and pretended he had something in his eye. “The pretext was so palpable that not a teammate came near him to inquire what was wrong,” John Wray noted in the Post-Dispatch. “Tom Jones approached within 10 feet and threw his handkerchief on the ground in front of the kneeling pitcher, walking back to first base without a word to him.”

According to the Globe-Democrat, “A large number of persons left the park in disgust, thinking that the Browns stood no chance of winning.”

More drama, though, was still to come.

In the ninth, Waddell fanned Topsy Hartsel for the record-setting 16th strikeout of the game, but the pitcher didn’t stick around to watch his teammates bat in the bottom half of the inning. Waddell went to the clubhouse and began to undress. He took off his shoes and socks, then heard a roar. The Browns were threatening.

“Barefooted, Rube rushed to the fence between the grandstand and bleachers,” James Crusinberry reported in the Post-Dispatch. “From his place behind the fence, he madly waved a towel,” urging his teammates on.

A combination of five hits and an error resulted in four runs, lifting Waddell and the Browns to a 5-4 triumph. Boxscore

High speed

According to Connie Mack and Nap Lajoie, the only pitcher of that time with more velocity than Waddell was a right-hander, Walter Johnson of the Senators. On Sept. 20, 1908, Johnson and Waddell were the starters in a game at St. Louis.

Waddell whiffed 14 in nine innings but the score was tied and he and Johnson had more work to do. Waddell fanned three more in the 10th, the last one with the bases loaded, giving him 17 strikeouts. In the bottom half, Danny Hoffman lined a single, scoring Tom Jones from second for a 2-1 Browns victory. “Rube Waddell had more sheer pitching ability than any man I ever saw,” Johnson said, according to the Baseball Hall of Fame. Boxscore

Waddell completed the 1908 season with a 19-14 record, a 1.89 ERA and 232 strikeouts. That remains the Browns/Orioles franchise record for most strikeouts in a season. Also, no other Browns/Orioles pitcher has matched Waddell’s 17 strikeouts in a game or his 16 whiffs in nine innings.

The 1910 Browns season was Waddell’s last in the big leagues. He totaled 193 wins with a 2.16 ERA. Waddell struck out 19.8 percent of all batters faced. The major-league average is 9.3, according to baseball-reference.com. In 1946, Waddell was inducted into the Baseball Hall of Fame.

A really good post Mark. Even though Rube Waddell is in the Hall of Fame he probably doesn’t receive the recognition that he deserves. I’ve got to say though Mark that I’m sort of torn in two. On one hand I ask myself what career Rube Waddell might have had without all the personal issues and eccentrics. But then I wonder if those very things actually contributed to his baseball accomplishments. It’s really humorous that he was linked to the straight laced Connie Mack. I would have never guessed that he still holds the single season strike out record for a Browns-Orioles pitcher. You have to wonder what his strikeout percentage would be in today’s swing for the fences hitting approach.

Thanks, Phillip. As The Sporting News noted of Rube Waddell, “There was no better pitcher than he when he was in form, but he was … aware of his powerlessness to resist temptation.”

Some stories regarding Connie Mack and Rube Waddell:

_ According to The Sporting News, the A’s were in St. Louis when Rube failed to show for a start. Browns catcher Jack O’Connor told Mack, “I walked over Grand Avenue from the water tower and saw Rube playing leapfrog with some kids near the fairgrounds.” Mack sent A’s catcher Osee Schrecongost to fetch Rube and coaxed him into the ballpark.

_ According to the St. Louis Star-Times, Rube got a $5,000 offer to leave the A’s and join the Pacific Coast League. When Rube informed Mack, the manager promised him a new Panama hat if he would stick through the season with the A’s. Next day, Mack purchased the hat and presented it to Rube, who from that time on was one of the most loyal members of the A’s.

_ According to the Philadelphia Inquirer, Rube was fumbling for his hotel room key when a revolver fell from his pocket and discharged. The bullet whizzed past Mack. In retelling the story, Mack referred to it as “the hotel episode in Pittsburgh.” Overhearing this, Rube said, “There ain’t no Hotel Episode in Pittsburgh, Mr. Mack.”

It is a large part of the appeal of baseball that it has a history of such characters. I’m still shaking my head over the idea of two pitchers going the distance in a 20-inning game.

After the A’s scored in the top of the 20th inning against Cy Young, Boston had a runner on second, one out, but Rube retired the next two batters to end the marathon.

Wishing you safety and warmth and electricity during the blizzard hitting your area, Ken. Thanks for taking the time to read and comment.