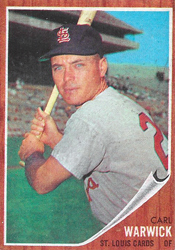

Carl Warwick seemed an unlikely candidate to shine for the Cardinals in the 1964 World Series.

A week before the season ended, Warwick suffered a fractured cheekbone when he was struck by a line drive during pregame drills. He underwent surgery the next day.

A week before the season ended, Warwick suffered a fractured cheekbone when he was struck by a line drive during pregame drills. He underwent surgery the next day.

After the Cardinals clinched the National League pennant in the season finale, manager Johnny Keane opted to put Warwick on the World Series roster as a pinch-hitter, even though he hadn’t swung a bat in a game in almost two weeks.

Warwick delivered, with three pinch-hit singles, two of which contributed to wins against the Yankees, and helped the Cardinals become World Series champions.

An outfielder who played for the Dodgers (1961), Cardinals (1961-62, 1964-65), Colt .45s (1962-63), Orioles (1965) and Cubs (1966), Warwick was 88 when he died on April 5, 2025.

Left and right

After leading Texas Christian University in hitting (.361) as a junior in 1957, Warwick got married and planned to start a family. So when Dodgers scout Hugh Alexander offered a contract in excess of $30,000, Warwick signed in December 1957, opting to skip his senior season. “I figured one year in pro ball would be worth more than a final year in college,” Warwick told the Austin American.

(Warwick earned a business administration degree from Texas Christian in 1961.)

He was the rare ballplayer who threw left and batted right. “I’m a natural southpaw,” Warwick said to the Los Angeles Mirror, “but as long as I can remember I’ve always picked up a bat with my right hand and hit right-handed.”

(Before Warwick, big-leaguers who threw left and batted right included outfielders Rube Bressler and Johnny Cooney, and first baseman Hal Chase.)

Though listed as 5-foot-10 and 170 pounds, Warwick looked shorter and lighter. As Joe Heiling of the Austin American noted, “Carl didn’t fill the popular image of a slugger. His shoulders weren’t broad as the side of a barn.”

In college, Warwick hit drives straightaway and to the gaps. To hit with power in the pros, he’d need to learn to pull the ball, said Danny Ozark, his manager at Class A Macon (Ga.). Taught by Ozark how to get out in front of pitches with his swing, Warwick walloped 22 home runs for Macon in 1958.

Moved up to Class AA Victoria (Texas) in 1959, Warwick roomed with future American League home run champion Frank Howard and tore up the Texas League, hitting .331 with 35 homers and scoring 129 runs. Victoria manager Pete Reiser, the St. Louis native and former Dodgers outfielder, rated Warwick a better all-around prospect than Howard.

“Carl can play there (in the majors) sooner than Howard,” Reiser told the Austin American. “Carl has a better knowledge of the strike zone than Howard and he’s starting to hit the curveball. To me, that’s a sign that a hitter is coming into his own. You won’t find any better than Carl. Defensively, there’s not too many better than him in the minors or big leagues. He can go get the ball.”

Climbing another notch to Class AAA in 1960, Warwick was a standout for St. Paul (Minn.), with 104 runs scored and double digits in doubles (27), triples (11) and homers (19).

Seeking a chance

Warwick, 24, opened the 1961 season with the Dodgers, who were loaded with outfielders. A couple were veterans (Wally Moon, Duke Snider); most, like Warwick, hadn’t reached their primes (Tommy Davis, Willie Davis, Don Demeter, Ron Fairly, Frank Howard). In May, the Dodgers sent Warwick and Bob Lillis to the Cardinals for Daryl Spencer. According to the St. Louis Globe-Democrat, Cardinals manager Solly Hemus called Warwick the “key man for us” in the deal and named him the center fielder, replacing Curt Flood. “Warwick fits into our future plans very well,” Hemus told the Los Angeles Mirror.

Warwick’s first hit for the Cardinals was a home run he pulled over the fence in left against Bob Buhl of the Braves at Milwaukee. Of his first 12 hits for St. Louis, seven were for extra bases _ four doubles, one triple, two homers. Boxscore

Harry Walker, the Cardinals’ hitting coach, didn’t want Warwick swinging for the fences, though, and suggested he alter his approach.

“He said I didn’t have the power to hit the ball out,” Warwick told the Austin American. “He said I wasn’t strong enough. He wanted me to punch the ball to right field. After you’ve been hitting a certain way so long, it’s hard to change. He made me go to a heavier bat with a thicker handle.”

Out of sync, Warwick said he tried hitting one way in batting practice, then another in games. On July 4, his season average for the Cardinals dropped to .217. Two days later, Solly Hemus was fired and replaced by Johnny Keane, who reinstated Flood in center. Warwick was dispatched to the minors. “We’re sending him out so that he’ll have a chance to play every day the rest of the season,” Keane told the Globe-Democrat.

Houston calling

The next year, Warwick figured to stay busy with the 1962 Cardinals subbing for their geriatric outfielders, Minnie Minoso in left and Stan Musial in right. (“Our outfield has Old Taylor and Ancient Age with a little Squirt for a chaser,” Flood quipped to the St. Louis Post-Dispatch.)

However, when an expansion club, the Houston Colt .45s, offered the Cardinals a pitcher they’d long coveted, Bobby Shantz, they couldn’t resist. On May 7, 1962, the Cardinals swapped Warwick and John Anderson for Shantz.

The trade was ill-timed for the Cardinals. Four days later, Minoso fractured his skull and right wrist when he crashed into a wall trying to snare a drive.

Warwick became Houston’s center fielder. In his first appearance in St. Louis after the trade, he produced four hits and a walk, including four RBI against Bob Gibson with a two-run double and a two-run homer. (For his career, Warwick hit .333 versus Gibson.) Boxscore

In addition to Gibson, Warwick also homered against Don Drysdale, Sandy Koufax and Juan Marichal that season.

When Cardinals general manager Bing Devine had a chance to reacquire Warwick, he swapped Jim Beauchamp and Chuck Taylor for him on Feb. 17, 1964.

Shifting roles

On Opening Day in 1964 against the Dodgers’ Sandy Koufax, Warwick was the Cardinals’ right fielder, with Flood in center and Charlie James in left. Boxscore

After two months, the club determined an outfield overhaul was needed. Flood remained, but Lou Brock was acquired from the Cubs in June to replace James and Mike Shannon was promoted from the minors in July to take over in right. Warwick primarily became a pinch-hitter.

He went to Cardinals coach Red Schoendienst and pinch-hitter deluxe Jerry Lynch of the Pirates for advice on how to perform the role. “Both of them agree you’ve got to be ready to attack the ball,” Warwick told Newsday.

On Sept. 27, 1964, before a game at Pittsburgh, Warwick was walking to the sidelines from the outfield during warmup drills when a line drive from a fungo bat swung by pitcher Ron Taylor struck him in the face, fracturing his right cheekbone. The next day, in St. Louis, Cardinals surgeon Dr. I.C. Middleman and plastic surgeon Dr. Francis Paletta performed an operation to repair the damage.

When the World Series began on Oct. 7 in St. Louis, Warwick was on the Cardinals’ roster, even though he hadn’t played in a game since Sept. 23. He also hadn’t produced a RBI since Aug. 2 or a home run since May 8.

However, as Keane explained to columnist Bob Broeg, “Pinch-hitting, Carl is extremely aggressive.”

Big hits

With the score tied at 4-4 in the sixth inning of World Series Game 1 at St. Louis, the Cardinals had Tim McCarver on second, two outs, when Warwick was sent to bat for pitcher Ray Sadecki. As Warwick stepped to the plate against the Yankees’ Al Downing, “my head was aching and my (scarred) cheek was hurting,” he later told United Press International.

Warwick whacked Downing’s first pitch past shortstop Phil Linz for a single, scoring McCarver and putting the Cardinals ahead to stay. St. Louis won, 9-5. Video, Boxscore

“I went up there with the idea of swinging at the first one if it was anywhere close,” Warwick told the Post-Dispatch. “I was looking for a fastball and I got one.”

In Game 2, Warwick, batting for second baseman Dal Maxvill in the eighth, singled and scored against Mel Stottlemyre. Batting again for Maxvill in Game 3, Warwick was walked by Jim Bouton.

The Cardinals, though, were in trouble. The Yankees won two of the first three and led, 3-0, in Game 4 at Yankee Stadium as Downing limited the Cardinals to one hit through five innings.

Needing a spark, Warwick provided one. Sent to bat for pitcher Roger Craig leading off the sixth, Warwick stroked a single on Downing’s second pitch to him.

“I seem to carry a different attitude up there coming cold off the bench,” Warwick told Joe Donnelly of Newsday. “I wouldn’t call it confidence. I come up there swinging. You’ve only got three swings. I don’t want to pass up an opportunity.”

The Cardinals loaded the bases with two outs before Ken Boyer clouted a Downing changeup for a grand slam and a 4-3 triumph. Video, Boxscore

Warwick’s three hits as a pinch-hitter tied a World Series record. The Yankees’ Bobby Brown (1947) and the Giants’ Dusty Rhodes (1954) also produced three pinch-hits in one World Series. Since then, Gonzalo Marquez of the Athletics (1972) and Ken Boswell of the Mets (1973) matched the mark.

(Allen Craig of the Cardinals had four career World Series pinch-hits _ two in 2011 and two more in 2013 _ but not three in one World Series.)

With a chance for a record fourth pinch-hit, Warwick batted for Maxvill in Game 6 but Bouton got him to pop out to third baseman Clete Boyer.

The Cardinals clinched the championship in Game 7, but for Warwick the good vibes didn’t last long. Bob Howsam, who replaced Bing Devine as Cardinals general manager, sent Warwick a contract calling for a $1,000 pay cut. “An insult,” Warwick told the Associated Press.

The magic of 1964 was gone in 1965. Warwick had one hit in April, one more in May and entered June with an .077 batting average. In July, the Cardinals shipped him to the Orioles, who traded him to the Cubs the following spring.

Bing Devine, who as Cardinals general manager twice traded for Warwick, became Mets general manager and acquired him again. Warwick, 29, was invited to try out at 1967 spring training for a reserve spot with the Mets but declined, opting to embark on a real estate career.

Dubbed the “Frank Sinatra of baseball” for his singing, Mazar, like Ol’ Blue Eyes, was from New Jersey. Sinatra’s hometown was Hoboken, site of the first organized baseball game played in 1846 between the Knickerbocker Club and New York Nine. Mazar grew up in High Bridge, a mere 50 miles from Hoboken but, otherwise, worlds apart.

Dubbed the “Frank Sinatra of baseball” for his singing, Mazar, like Ol’ Blue Eyes, was from New Jersey. Sinatra’s hometown was Hoboken, site of the first organized baseball game played in 1846 between the Knickerbocker Club and New York Nine. Mazar grew up in High Bridge, a mere 50 miles from Hoboken but, otherwise, worlds apart. On March 28, 1970, the East-West Major League Baseball Classic was played at Dodger Stadium in Los Angeles. According to the National Baseball Hall of Fame, the Saturday afternoon exhibition netted more than $30,000 for two beneficiaries:

On March 28, 1970, the East-West Major League Baseball Classic was played at Dodger Stadium in Los Angeles. According to the National Baseball Hall of Fame, the Saturday afternoon exhibition netted more than $30,000 for two beneficiaries: Players from the East divisions of the American and National leagues were placed on an East team. The West team had players from the West divisions of both leagues. That gave fans the chance to see Angels and Dodgers, Mets and Yankees, and Athletics and Giants perform as teammates.

Players from the East divisions of the American and National leagues were placed on an East team. The West team had players from the West divisions of both leagues. That gave fans the chance to see Angels and Dodgers, Mets and Yankees, and Athletics and Giants perform as teammates. In the long history of the franchise, Lee is the only Cardinal to play in just one game for them and have a 1.000 batting average.

In the long history of the franchise, Lee is the only Cardinal to play in just one game for them and have a 1.000 batting average. The correct spelling, though, was C, for closer, because that’s what Caudill became in the American League after beginning his career with the Cardinals.

The correct spelling, though, was C, for closer, because that’s what Caudill became in the American League after beginning his career with the Cardinals.