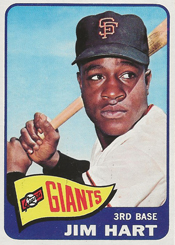

As a rookie with the reigning National League champion Giants in 1963, Jim Ray Hart learned the hard way that facing the Cardinals could be a pain.

On his first day playing in the majors, Hart suffered a fractured left collarbone when struck by a Bob Gibson pitch.

On his first day playing in the majors, Hart suffered a fractured left collarbone when struck by a Bob Gibson pitch.

A month later, when he returned to the lineup, Hart was hit in the head by a pitch from the Cardinals’ Curt Simmons, ending his season.

Early times

Hart hailed from Hookerton, a town of about 500 residents, 40 miles from the nearest interstate, in eastern North Carolina. At 15, he began drinking corn whiskey, and his hankering for the homemade hooch led to heavier drinking later on, Hart told the Santa Rosa (Calif.) Press Democrat.

When he was 18, Hart signed with the Giants and entered their farm system. In 1961, he played shortstop but made 42 errors in 77 games. He did less damage at third base and in the outfield, and settled into those spots.

Hart’s hitting was what made him special. A right-handed slugger, he had a .421 on-base percentage and 123 RBI for Fresno in 1961, and a .403 on-base percentage and 107 RBI for Springfield (Massachusetts) in 1962.

After producing 99 hits in 83 games for Tacoma in 1963, Hart, 21, was called up to the Giants in July.

Hard lessons

Hart made his Giants debut in the first game of a July 7 doubleheader against the Cardinals at San Francisco’s Candlestick Park. His first big-league hits in that game were singles against Bobby Shantz and Lew Burdette. Hart also walked twice, scored a run and drove in one, helping the Giants to a 4-3 victory in 15 innings. Boxscore

Between games, Willie Mays reminded Hart that Bob Gibson was starting Game 2. In the book “Stranger to the Game,” Hart recalled, “I only half-listened to what he was saying, figuring it didn’t make much difference.”

Hart faced Gibson for the first time in the second inning. Gibson’s velocity that Sunday afternoon was exceptional. Cardinals catcher Tim McCarver told the St. Louis Post-Dispatch, “Gibson was so fast, I didn’t think my hands would hold out.”

In the book “Sixty Feet, Six Inches,” Gibson said the word on Hart was to pitch him inside because “he was a guy who’d kill you if you got the ball away from him. I was making sure he wasn’t going to kill me.”

In the batter’s box, “I started digging a little hole with my back foot to get a firm stance as I usually did,” Hart said in “Stranger to the Game.” “No sooner did I start digging that hole than I hear Willie (Mays) screaming from the dugout, ‘Nooooo!’ I should have listened to Willie.”

Gibson’s first pitch to Hart was tight. “He had a closed stance, with his left foot nearly on home plate, and was unable to move quickly enough to avoid an inside pitch, which I was obligated to throw as long as he cheated toward the outside corner,” Gibson said in “Stranger to the Game.”

Hart dug in again for the next pitch, a fastball up and in, and it struck him with such force that “there was a loud crack,” he said in “Stranger to the Game.”

Hart collapsed in agony. Taken to a hospital, he was found to have “a clavicle fracture about the size and roundness of a baseball,” the San Francisco Examiner reported. (Sixteen years later, in 1979, Hart told the Oakland Tribune, “I still can feel a small pain in my shoulder sometimes from that.”)

Gibson said his pitch was intended to move Hart away from the plate, not hit him. When informed Hart had a fractured bone, Gibson replied to the Examiner, “I’m sorry, but I don’t know what I can do about it. I know I wasn’t throwing at him.”

Hart told the newspaper, “I don’t think he was trying to throw at me, but I don’t know. He says he was pitching me tight … I wasn’t fooled on the pitch. It was just that it was in back of me … I just didn’t have a chance to avoid that pitch.”

The Giants were irate _ “It’s a terrible thing to have happen to him on his first day,” manager Al Dark told the Examiner. “It’s a disgrace” _ and retaliated.

When Gibson batted in the third, Juan Marichal “threw a fastball at Gibson’s head that dumped him into the dirt and almost uncoupled him,” the Examiner reported.

Plate umpire Al Barlick rushed toward the mound, shook a finger at Marichal and warned him not to do that again.

“I think Marichal was throwing at me,” Gibson said to the Oakland Tribune. “If I had been throwing at the kid (Hart), it would have been justified. I wasn’t.”

In “Stranger to the Game,” Gibson said, “There was a big difference between throwing at a guy and brushing him back. The brushback pitch is a lot like the spitball in the sense that its effectiveness lies largely in the awareness it places in the batter’s mind.”

Stan Musial, 42, broke up the scoreless duel in the seventh with a two-run home run against Marichal. In the ninth, Gibson laced a two-run single versus reliever Jim Duffalo. Gibson pitched a six-hit shutout and the Cardinals won, 5-0. Boxscore

Down and out

Hart returned to the lineup on Aug. 12. Four nights later, with the Cardinals ahead, 13-0, in the ninth inning at St. Louis, he faced Curt Simmons and was struck on the left temple by an 0-and-2 fastball. “The ball hit the lower part of the helmet and Hart’s head,” the Examiner reported.

Simmons told the newspaper, “He never backed away. He seemed to freeze and stand right there.”

Hart slumped to the ground and was carried on a stretcher to the clubhouse. Cardinals manager Johnny Keane, who as a minor-leaguer suffered a fractured skull when clunked in the head by a pitch, went to the Giants’ clubhouse and stayed until an ambulance came, according to the Oakland Tribune.

Hart was diagnosed with a concussion. At the hospital, he “was speaking coherently” and was given permission to eat and smoke, Cardinals physician Dr. I.C. Middleman told the Examiner. Boxscore

Back in San Francisco, Hart complained of dizziness, headaches and blurred vision. He was examined by a neurosurgeon and shut down for the season.

Take that!

A year later, Hart tagged Gibson and Simmons with home runs.

On Aug. 10, 1964, Hart hit “a majestic home run over the scoreboard in left” at St. Louis against Gibson, the Oakland Tribune reported. “It was estimated the ball traveled around 500 feet. It cleared the scoreboard, which is 60 feet high at that particular spot, 408 feet from the plate.”

The ball landed on Sullivan Avenue. Boxscore

Two weeks later, at Candlestick Park, Hart hammered a two-run homer versus Simmons. Boxscore

Hart finished the 1964 season with 31 home runs. In 1965, he led the Giants in hits (177) and doubles (30) and batted .329 against the Cardinals. Hart made the National League all-star team in 1966, belting 33 homers and leading the Giants in hits (165) again.

The 1967 season may have been Hart’s best. He was the Giants leader in runs scored (98), hits (167), doubles (26), triples (seven), RBI (99), walks (77) and total bases (294). On June 29, 1967, Hart had four RBI on a single and a home run in the opening inning against Gibson.

Troubled times

Too many injuries, too much weight gain and too much drinking contributed to Hart’s decline.

He tore muscles in his right shoulder while making a throw from the outfield and was hit in the head again by a pitch from the Reds’ Wayne Simpson. Struck by pitches 28 times in the majors, Hart was called “Mr. Dent” by his teammates, United Press International reported.

On Oct. 30, 1968, a car driven by Hart struck and killed a woman in Daly City, Calif. Dorothy Selmi, 62, wife of former Daly City mayor Paul Selmi, was hit as she was crossing Mission Street at Como Avenue, the Examiner reported. Hart was questioned by police and released.

In April 1969, Hart crashed against the fence at Candlestick Park while chasing a Pete Rose drive and bashed his right shoulder. He was limited to 236 at-bats that season. “When I hit the ball, the pain goes from a nerve in my back, high on the shoulder, and winds up in my elbow,” Hart told the Examiner.

Hart batted .304 as a pinch-hitter in 1969. A highlight came on July 26 when he slugged a two-run homer in the ninth inning against Joe Hoerner to beat the Cardinals. Boxscore

During his playing days, Hart drank a lot. His preference was I.W. Harper whiskey. “A quart a day,” he said to Bob Padecky of the Santa Rosa Press Democrat. Hart told Padecky that Giants manager Herman Franks offered him money to stop drinking, but he couldn’t.

“I think I could have played longer in the big leagues if I hadn’t done as much drinking,” Hart said to Pat Frizzell of the Oakland Tribune.

In April 1973, the Giants sent Hart to the Yankees and he finished his playing days with them in 1974, totaling 1,052 career hits.

Regardless of the locale, Joaquin Andjuar, the self-proclaimed “One Tough Dominican” pitcher, could back up his image with astonishing results.

Regardless of the locale, Joaquin Andjuar, the self-proclaimed “One Tough Dominican” pitcher, could back up his image with astonishing results. Though he’d been a productive infielder, mostly at second base and third for the Astros, Howe was unemployed at the start of 1984. He sat out the 1983 season because of elbow and ankle surgeries, then became a free agent and, at 37, hoped to show he still could play.

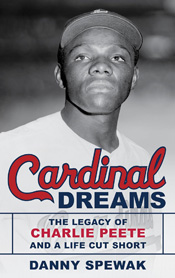

Though he’d been a productive infielder, mostly at second base and third for the Astros, Howe was unemployed at the start of 1984. He sat out the 1983 season because of elbow and ankle surgeries, then became a free agent and, at 37, hoped to show he still could play. An outfielder and minor league batting champion in the Cardinals system, Peete was on the cusp of becoming a prominent player in the majors.

An outfielder and minor league batting champion in the Cardinals system, Peete was on the cusp of becoming a prominent player in the majors. In 1968, DiMaggio was in a green and gold Oakland Athletics uniform, giving instruction to players. La Russa was trying to make the team as a reserve infielder and return to the majors for the first time in five years.

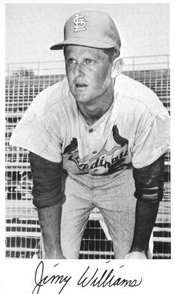

In 1968, DiMaggio was in a green and gold Oakland Athletics uniform, giving instruction to players. La Russa was trying to make the team as a reserve infielder and return to the majors for the first time in five years. A middle infielder whose professional baseball experience consisted of one season at the Class A level of the minors, Williams got his first at-bat in the majors against none other than Sandy Koufax. His second plate appearance also came against a future Hall of Famer, Juan Marichal.

A middle infielder whose professional baseball experience consisted of one season at the Class A level of the minors, Williams got his first at-bat in the majors against none other than Sandy Koufax. His second plate appearance also came against a future Hall of Famer, Juan Marichal.