They were a couple of neighborhood guys from the Bedford-Stuyvesant section of Brooklyn. Lenny and Tommy. Common names. Uncommon talents.

Lenny Wilkens and Tommy Davis grew up playing stickball and church league basketball against one another. At Boys High School, they became friends.

Davis was a prep baseball and basketball standout. Wilkens was trying to find his way. When Wilkens was a senior, he acted on Davis’ suggestion and went out for the basketball team. It opened the door to a lifetime of opportunity.

Wilkens became a player and coach in the NBA. He was elected to the Naismith Basketball Hall of Fame for success in both roles. Davis became a big-league baseball player. He was a two-time National League batting champion and twice hit game-winning home runs against Bob Gibson.

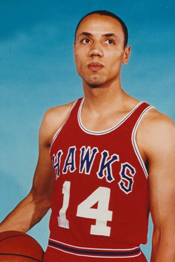

St. Louis was where Wilkens began his pro career. The best of his eight seasons for the St. Louis Hawks was 1967-68 when the slender guard was runner-up to a giant, Wilt Chamberlain, for the NBA Most Valuable Player Award.

As a player, Wilkens twice led the NBA in assists (1969-70 and 1971-72). As a coach, he led the Seattle SuperSonics to a NBA title (1978-79) and amassed 1,332 wins. Only Gregg Popovich (1,390) and Don Nelson (1,335) achieved more wins as NBA coaches. Wilkens was 88 when he died on Nov. 9, 2025.

Hard road to travel

Wilkens was the son of a black father and white mother. He was about kindergarten age when his father, a chauffeur, died of a perforated ulcer.

Lenny’s mother, Henrietta, raised him and his three siblings in a cold-water tenement flat. Heat came from a coal stove. They survived “on powdered milk and peanut butter,” according to the New York Daily News.

“Quite frankly, it is a mystery to me how any kid was able to make it under such circumstances,” Rev. Thomas Mannion, a parish priest at Brooklyn’s Holy Rosary Catholic Church, told the New York Times.

Henrietta worked in a candy factory. At 8, Lenny got a job in a market, scrubbing floors and delivering groceries. Father Mannion became a surrogate dad. “I had great faith in him,” Wilkens said to the New York Times. “I’d get discouraged and sometimes pretty angry, but Father Mannion … was always there to prod me and keep me from giving up.”

In 1979, Wilkens’ wife, Marilyn, told the newspaper that Father Mannion “was a tremendous influence on (Lenny). He kept him out of trouble in those early days when Lenny was growing up in a very bad neighborhood.”

Wilkens was an altar boy. According to the Los Angeles Times, Tommy Davis recalled a day during their youth when police frisked Wilkens for switchblades and instead found only rosary beads. As Father Mannion told the New York Times, “He somehow rose above the neighborhood.”

The priest was among the first to teach Wilkens about basketball, “setting up chairs for Wilkens to dribble in and out of in the Holy Rosary gym,” according to the New York Daily News.

Get in the game

Wilkens had a bad experience the first time he tried out for the high school basketball team. Coach Mickey Fisher “inadvertently whacked him in the face with his hand as he demonstrated a technique,” the New York Daily News reported.

Offended, Wilkens left and stayed away from the basketball team his first three years in high school. Meanwhile, Tommy Davis developed into an all-city forward. As Davis recalled to United Press International, early in their senior year he said to his friend, “Come on out and play, man. You know Mickey didn’t mean it. You can make this team. We need you.”

Father Mannion also urged Wilkens to try out for the team because he saw basketball as a path to a college scholarship.

Wilkens relented and made the team for the 1955-56 season. However, he was scheduled to graduate in January 1956. So he played in just seven games before receiving his diploma and leaving school.

Undeterred, Father Mannion wrote to a friend, a priest, Rev. Aloysius Begley, athletic director at Providence College, and asked him to consider awarding Wilkens a basketball scholarship. Providence coach Joe Mullaney wanted Tommy Davis, but the Brooklyn Dodgers signed him. After Mullaney’s father scouted Wilkens in a New York summer tournament and recommended him, Providence gave the scholarship.

Wilkens was thin and barely taller than 6-foot. Though his features were frail, he had a basketball toughness honed from playing against older, bigger foes on the Brooklyn playgrounds. He was an aggressive defender and an electric playmaker. As Wayne Coffey of the New York Daily News noted, Wilkens had “the body of a twig and the hands of pickpocket, and a calm that followed him like a shadow.”

An economics major who spent summers working on Brooklyn docks loading cargo, Wilkens planned to teach. He was surprised when St. Louis selected him with the sixth pick in the first round of the 1960 NBA draft. The top two picks were Oscar Robertson (Cincinnati Royals) and Jerry West (Los Angeles Lakers).

“I never thought I was good enough to play up there,” Wilkens told the Springfield (Mass.) Republican. “Playing pro ball after I graduated from Providence wasn’t on my list of things to do.”

Tasked with trying to convince Wilkens he could succeed, St. Louis scout Stan Stutz took him to his first NBA game _ Hawks at Boston in the playoffs. “Stutz told me to watch the play of the Hawks guards (Sihugo Green and Johnny McCarthy),” Wilkens recalled to the Springfield newspaper. “After watching them, I told myself I could play as good as those guys. That’s when I decided I had a chance to make it in the NBA.”

The right stuff

Wilkens was correct about his abilities. He excelled in the NBA as a savvy backcourt talent and unassuming team leader. “The quietest man ever to come out of Brooklyn,” Frank Deford of Sports Illustrated described him.

When he joined the Hawks, Wilkens’ job was to pass the ball to the frontcourt trio of Bob Pettit, Cliff Hagan and Clyde Lovellette. “It was pattern ball, not really my game,” Wilkens told Sports Illustrated, “but you had to adjust to it.”

The cast of teammates eventually changed but Wilkens remained the constant, running the show on the floor. “He can dribble through a briar patch,” Sports Illustrated declared. “He knows the perfect pass to make and, perhaps more important, realizes that most often it need not be a fancy one … Best of all, he has the ability to pace a game, to enforce a tempo.”

Wilkens did it all without fanfare. Frank Deford described him as “shy, with mournful brown eyes.” Jim Murray of the Los Angeles Times noted, “He looks constantly as if he got bad news from home or a telegram from the front. He makes a basset hound look happy.”

Before the 1967-68 season, coach Richie Guerin gave Wilkens the green light to run a fast-break offense and pressure defense. Wilkens made it work. He was the quarterback of a team that included Zelmo Beaty, Bill Bridges, Joe Caldwell, Lou Hudson and Paul Silas. The Hawks won 16 of their first 17 games. Wilkens “is more responsible for our success than anybody,” Guerin told Jim Murray.

For the season, Wilkens averaged 20 points and 8.3 assists per game. He had a triple double _ 30 points, 12 rebounds, 13 assists _ in an October game against the New York Knicks, and was unstoppable (39 points, 18 assists) in a January win versus Seattle. Game stats and Game stats

Hawks management declared the 1967-68 regular-season finale, a home game against Seattle, as “Lenny Wilkens Night.” In a halftime ceremony, the club gave him a green Cadillac and other gifts. Cardinals baseball outfielder Curt Flood, an artist, did an oil painting of Wilkens and presented it to him. Then Wilkens went back to work. He finished the game with 19 points and 19 assists. Game stats

Facing the San Francisco Warriors in the playoffs, the Hawks were beaten in four of six games. The second of their two wins came in Game 5 at home when Wilkens had 20 points and 10 assists. It turned out to be the last game for the Hawks in St. Louis. The franchise relocated to Atlanta in May 1968. Game stats

Enduring friendship

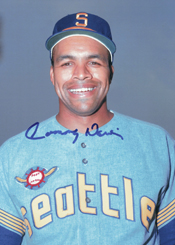

Wilkens never played for Atlanta. On Oct. 12, 1968, he was traded to Seattle for Walt Hazzard. Three days later, Tommy Davis was selected by the Seattle Pilots in the American League expansion draft.

More than a decade after Davis convinced Wilkens to try out for high school basketball, the two friends were reunited nearly 3,000 miles from Brooklyn as professional athletes in Seattle.

More than a decade after Davis convinced Wilkens to try out for high school basketball, the two friends were reunited nearly 3,000 miles from Brooklyn as professional athletes in Seattle.

As a boy, baseball was Wilkens’ sport of choice, according to the New York Daily News. During the spring and summer of 1969, Wilkens seldom missed a Seattle Pilots home game, the Tacoma News Tribune reported. He’d wait for Davis outside the clubhouse afterward.

Though he was traded to Houston on Aug. 30, 1969, Davis at season’s end was the Pilots’ leader in RBI (80) and doubles (29).

Grateful for the time he and Wilkens had together that year, Davis told Sports Illustrated, “I love Lenny. He is … a true friend who can be depended upon … He is steadfast and honorable … I love Lenny for what he has achieved. He went in there with all those big guys and proved to them he could do it on quickness and guts and dedication. We used to say of him that he was like the man who wasn’t there _ he wasn’t there until you read the box score.”

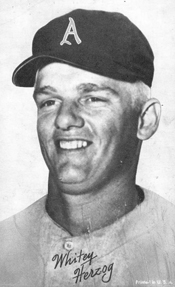

A journeyman outfielder, Herzog squeezed out every bit of talent he had, lasting eight seasons in the majors, mostly with losing teams, before the Tigers removed him from their big-league roster after the 1963 season. The Tigers offered him a role as player-coach at Syracuse, with a promise he’d be considered for a managerial job in their farm system some day, the Detroit Free Press reported. The Kansas City Athletics proposed he join them as a scout.

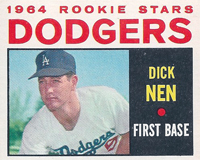

A journeyman outfielder, Herzog squeezed out every bit of talent he had, lasting eight seasons in the majors, mostly with losing teams, before the Tigers removed him from their big-league roster after the 1963 season. The Tigers offered him a role as player-coach at Syracuse, with a promise he’d be considered for a managerial job in their farm system some day, the Detroit Free Press reported. The Kansas City Athletics proposed he join them as a scout. On Sept. 18, 1963, in his second at-bat in the majors, Nen slammed a home run for the Dodgers, tying the score in the ninth inning and stunning the Cardinals. The Dodgers went on to win, completing a series sweep that put them on the verge of clinching a pennant.

On Sept. 18, 1963, in his second at-bat in the majors, Nen slammed a home run for the Dodgers, tying the score in the ninth inning and stunning the Cardinals. The Dodgers went on to win, completing a series sweep that put them on the verge of clinching a pennant.

A left-handed batter whose stroke regularly produced highly elevated line drives, Bottomley totaled 42 doubles, 20 triples and 31 home runs in 1928, the year he earned the National League Most Valuable Player Award and helped the Cardinals win their second pennant.

A left-handed batter whose stroke regularly produced highly elevated line drives, Bottomley totaled 42 doubles, 20 triples and 31 home runs in 1928, the year he earned the National League Most Valuable Player Award and helped the Cardinals win their second pennant. On May 30, 1946, in the second game of an afternoon doubleheader against the Dodgers, Rowell launched a towering drive to right. The ball struck the Bulova clock high atop the scoreboard at Ebbets Field in Brooklyn, shattering the dial’s neon tubing and showering right fielder Dixie Walker with falling glass. As the New York Times put it, “The clock spattered minutes all over the place.”

On May 30, 1946, in the second game of an afternoon doubleheader against the Dodgers, Rowell launched a towering drive to right. The ball struck the Bulova clock high atop the scoreboard at Ebbets Field in Brooklyn, shattering the dial’s neon tubing and showering right fielder Dixie Walker with falling glass. As the New York Times put it, “The clock spattered minutes all over the place.” Ebbets Field was packed with 35,484 spectators, the Dodgers’ largest home crowd of 1946. (Years later, the New York Times, noting Bernard Malamud was a Brooklynite “who haunted Ebbets Field as a youth,” pondered whether he was at the game and whether his experiences there reflected any scenes he wrote in “The Natural.”)

Ebbets Field was packed with 35,484 spectators, the Dodgers’ largest home crowd of 1946. (Years later, the New York Times, noting Bernard Malamud was a Brooklynite “who haunted Ebbets Field as a youth,” pondered whether he was at the game and whether his experiences there reflected any scenes he wrote in “The Natural.”)