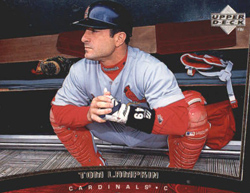

When the Cardinals got Tom Lampkin, it was not with the expectation he would be their Opening Day catcher in each of the next two seasons.

On Dec. 19, 1996, the Cardinals acquired Lampkin from the Giants for a player to be named. Two months later, the Giants chose pitcher Rene Arocha from a list of four players offered by the Cardinals, completing the deal.

On Dec. 19, 1996, the Cardinals acquired Lampkin from the Giants for a player to be named. Two months later, the Giants chose pitcher Rene Arocha from a list of four players offered by the Cardinals, completing the deal.

Lampkin was projected to be a backup, but when starter Tom Pagnozzi got injured in 1997 and 1998, Lampkin was in the Cardinals’ Opening Day lineup both years.

Supporting role

After graduating from the University of Portland with a degree in marketing and management, Lampkin reached the major leagues in September 1988 with the Cleveland Indians. The next year, he was traded to the Padres.

In 1991, Lampkin began a season on a major-league roster for the first time, serving as backup to Padres catcher Benito Santiago. The Padres traded Lampkin to the Brewers in 1993. The Giants signed him after the season when he became a free agent.

Lampkin spent a full season in the majors for the first time in 1995 when he was backup to Kirt Manwaring. After the Giants traded Manwaring to the Astros in July 1996, Lampkin became the starter.

“He’s done a good job with the young (pitchers), especially Shawn Estes and William VanLandingham,” Giants manager Dusty Baker told the San Francisco Examiner.

Lampkin nailed 17 of 33 runners attempting to steal (51.5 percent, best in the National League) in 1996 and didn’t allow a passed ball, but he became expendable when the Giants deemed Rick Wilkins and Marcus Jensen to be their catchers in 1997.

Good fit

The Cardinals had a three-time Gold Glove Award winner, Tom Pagnozzi, as their catcher, with Danny Sheaffer as the backup, but both were right-handed batters. Lampkin appealed to the Cardinals because he batted from the left side.

“This creates a little competition,” Cardinals general manager Walt Jocketty told the St. Louis Post-Dispatch after he acquired Lampkin.

Manager Tony La Russa said Lampkin “comes with really good endorsements from pitchers whom he’s caught and managers he’s played for. He’s a good thrower, has good hands and he’s a left-handed hitter who’s a dangerous out. I think this really adds balance to our catching corps.”

With the Giants in 1996, Lampkin had batted .264 versus right-handers and had one of his best games in May when he produced three hits and a walk and scored four times against the Cardinals. Boxscore

After joining St. Louis, Lampkin told the Post-Dispatch, “I don’t intend to be named the starting catcher, but I’m not going to lay down … I know La Russa. He’s the kind of manager who likes to keep all his players ready. Hopefully I’ll get to see some playing time.”

Stepping in

Lampkin’s value increased late in spring training of 1997 when Pagnozzi, 34, went on the disabled list because of a strained calf muscle.

The Cardinals began the regular season with Lampkin, 33, and Sheaffer, 35, as the catchers. Lampkin was the Opening Day starter against the Expos at Montreal Boxscore and in the Cardinals’ home opener. Boxscore

Pagnozzi missed the first 19 games of the season, returned and soon suffered a torn hip flexor, sidelining him until August.

The Cardinals called up Mike Difelice, 27, from Class AA and demoted Sheaffer. A defensive specialist, Difelice platooned with Lampkin.

Lampkin hit seven home runs, including a game-winner versus LaTroy Hawkins of the Twins on July 1. Boxscore

He batted .245 in 108 games for the 1997 Cardinals, but a mere .209 with runners in scoring position. He also disappointed as a pinch-hitter (.171).

Lampkin wasn’t as good on defense for the 1997 Cardinals as he was the year before with the Giants. He threw out 22 of 77 runners attempting to steal against him (29 percent) and was charged with six passed balls.

The Cardinals had five catchers make starts for them in 1997: Difelice (81), Lampkin (56), Eli Marrero (13), Pagnozzi (11) and Sheaffer (one). A right-handed batter, Marrero hit .273 with 20 home runs in the minors in 1997 and was considered the heir apparent to Pagnozzi

Helping hand

After the 1997 season, Difelice was selected by the Tampa Bay Rays in the expansion draft, leaving the Cardinals with a catching corps of Pagnozzi, Lampkin and Marrero.

What seemed a team strength turned into a weakness during 1998 spring training. Marrero, 24, had a cancerous thyroid gland removed in March. Pagnozzi became sidelined because of a shoulder problem.

When the Cardinals opened the 1998 regular season, Lampkin was their starting catcher. Boxscore “I prepared myself every spring to play every day,” Lampkin told the Post-Dispatch. “Now it’s paid off because it’s actually happening.”

Lampkin eventually split time with Marrero and Pagnozzi when they got healthy enough to return.

Noting Lampkin’s intensity, La Russa said, “He’s too gung-ho, too Marine-like to play every day. He’s a good player and there’s no question he’d do anything to try to win for this team.”

Lampkin hit .231 in 93 games for the 1998 Cardinals. He hit .246 with runners in scoring position and .304 as a pinch-hitter.

Lampkin also caught 13 of 43 runners attempting to steal against him (30 percent) and allowed four passed balls.

Marrero made 67 starts at catcher for the 1998 Cardinals. Lampkin had 54 starts and Pagnozzi made the rest.

Lampkin became a free agent after the 1998 season and was considered “most likely to return” to the Cardinals, the Post-Dispatch reported, but he opted to sign with the Mariners.

He spent three seasons with the Mariners as backup to Dan Wilson before finishing his playing career as the primary catcher for the 2002 Padres.

In his last eight seasons (1995-2002), Lampkin played for four managers who were among the game’s most successful: Dusty Baker, Tony La Russa, Lou Piniella and Bruce Bochy.

In December 1971, Clendenon connected with the Cardinals. Released by the Mets, the slugging first baseman worked out a deal to play for St. Louis.

In December 1971, Clendenon connected with the Cardinals. Released by the Mets, the slugging first baseman worked out a deal to play for St. Louis. Bill Virdon was an outfielder with the Yankees’ minor-league American Association club in Kansas City in 1953. Johnny Keane, managing the Cardinals’ Columbus, Ohio, club in the American Association, was impressed by Virdon’s defense, speed and throwing, and rated him ready for the big leagues.

Bill Virdon was an outfielder with the Yankees’ minor-league American Association club in Kansas City in 1953. Johnny Keane, managing the Cardinals’ Columbus, Ohio, club in the American Association, was impressed by Virdon’s defense, speed and throwing, and rated him ready for the big leagues. In June 1983, the Cardinals contacted the Reds with a trade offer for Bench. According to the Cincinnati Enquirer, the Cardinals were willing to send first baseman Keith Hernandez to the Reds for Bench and starting pitcher Frank Pastore.

In June 1983, the Cardinals contacted the Reds with a trade offer for Bench. According to the Cincinnati Enquirer, the Cardinals were willing to send first baseman Keith Hernandez to the Reds for Bench and starting pitcher Frank Pastore. In December 1981, the Phillies were prepared to deal Ryne Sandberg to the Brewers, but their offer was rejected. A month later, Sandberg was traded to the Cubs.

In December 1981, the Phillies were prepared to deal Ryne Sandberg to the Brewers, but their offer was rejected. A month later, Sandberg was traded to the Cubs. (Updated June 9, 2024)

(Updated June 9, 2024)