Whether trying to drive in a run against Bob Gibson or snare a Stan Musial line drive to stop a Cardinals rally, Ernie Banks often excelled on the baseball field. The rough-and-tumble arena of Chicago politics was quite a different matter.

In December 1962, a month before he turned 32, Banks said he would run as a Republican candidate in the election for 8th Ward alderman in Chicago. A two-time winner of the National League Most Valuable Player Award, the slugger said he planned to continue his playing career with the Cubs while serving as alderman.

In December 1962, a month before he turned 32, Banks said he would run as a Republican candidate in the election for 8th Ward alderman in Chicago. A two-time winner of the National League Most Valuable Player Award, the slugger said he planned to continue his playing career with the Cubs while serving as alderman.

Though popular in Chicago _ he was nicknamed Mr. Cub _ Banks soon learned that being liked didn’t necessarily translate into votes, even with fellow Republicans and certainly not against a Democrat-controlled organization run by machine boss Mayor Richard J. Daley.

Mean streets

Banks’ desire to run for local office may have stemmed from an incident that occurred at his Chicago home.

On July 1, 1962, a bullet was fired through a window of Banks’ house at 8159 Rhodes Avenue, the Chicago Tribune reported. Banks was on a road trip with the Cubs, but his pregnant wife, Eloyce, and 3-year-old twin sons were in the house, along with Eloyce’s aunt, Mary Jones. No one was injured.

Eloyce Banks said she heard two shots fired in a gangway and at the rear of her home about 1 a.m., shortly after she returned from attending a debutante cotillion for Jacqueline Barrow, daughter of boxer Joe Louis, at the iconic Palmer House hotel, the Associated Negro Press news service reported.

According to the Tribune, Eloyce and her aunt found the window of a breakfast nook had been pierced by a bullet. A .38 caliber slug was found on the floor.

Mrs. Banks told police six teens were gathered near the house, shouting abusive remarks, Associated Negro Press reported.

“Police said they believed the bullet fired into the Banks home was the outgrowth of general rowdiness rather than personal malice against the ballplayer or his family,” according to the Tribune.

Ernie Banks said to the newspaper, “This upsets me tremendously … There have been quite a few boys, and girls, too, hanging around the corners in our areas, making wisecracks, noise and so forth … It seems that in the summer they have parties and things, then gather on the street after the parties break up.”

Urban leader

Five months later, Banks announced his candidacy for the 8th Ward alderman seat. “There has been some trouble in our community,” Banks told the Chicago Defender. “It’s the kind that happens in any community, but I just think many people don’t pay attention to teenagers.”

Banks’ agent, Herman M. Peterson, said to the Tribune, “He wants to get into politics primarily so he can do everything in his power to help youth.”

An aide to U.S. Senator Everett Dirksen, an Illinois Republican, encouraged Banks to run, the Tribune reported. Banks told the Chicago Defender, “I said all right, providing it did not interfere with my baseball. It won’t.”

(Dirksen was Senate Minority Leader at the time Banks ran. Dirksen went on to have a crucial role in the passage of the Civil Rights Act of 1964, working to craft a bipartisan compromise that secured votes to overcome a Senate filibuster.)

In Chicago, an alderman is the equivalent of what might be more commonly known elsewhere as a city council member. The 8th Ward was located in Chicago’s South Side and encompassed areas such as Calumet Heights, Chatham and South Shore. Banks resided in Chatham. So, too, at the time did gospel singer Mahalia Jackson and future sports commentator Michael Wilbon.

The 8th Ward alderman seat was held by a Democrat, James Condon. He’d been a Chicago police sergeant while attending night classes at DePaul, where he earned a law degree. As assistant state’s attorney for Cook County, Condon helped establish the nation’s first narcotics court, declaring in 1951 that “dope is as plentiful for kids on the South Side as lollipops,” the Tribune reported.

Before Condon, aldermen who served the 8th Ward included:

_ William Meyering, a U.S. military officer who had his right arm amputated after he was wounded in combat at Verdun, France, during World War I. Meyering received the Distinguished Service Cross for gallantry.

_ David L. Sutton, who received a blackmail note that said his 5-year-old son would be harmed unless the alderman placed $5,000 in a tomato can and left it, as instructed, in a vacant lot. Sutton gave the note to police detectives and his son was not abducted.

Rough stuff

Before announcing his candidacy, Banks didn’t seek the endorsement of the local Republican leadership. His entry into the race brought an unenthusiastic reaction from Michael J. Connelly, 8th Ward Republican committeeman, who indicated Banks’ busy baseball schedule would keep him from fulfilling an alderman’s responsibilities. Several other people were under consideration to be the endorsed Republican candidate, Connelly told the Tribune.

“Banks plans to buck the power of Michael J. Connelly … by running for alderman,” the Chicago Defender noted. “It is expected that Connelly will offer opposition to Banks’ move.”

Asked about Banks’ candidacy, Benjamin Lewis, Democratic alderman from the 24th Ward, told the Tribune, “He’s a minor leaguer as far as politics is concerned.”

(Two months later, a couple of days after he overwhelmingly was re-elected alderman of the 24th Ward, Lewis was found shot to death in his office. He was handcuffed and shot three times in the head with a .32 caliber automatic pistol. No suspect was arrested and the case remains unsolved.)

Banks did have the support of Cubs owner Philip K. Wrigley and the editorial board of the Tribune.

“I talked to the boss, Mr. Wrigley, and he told me it isn’t often one would get an opportunity like the one I have been offered,” Banks said to the Chicago Defender.

In an editorial, the Tribune described Banks as “a promising candidate” and “an intelligent public-spirited citizen” whose candidacy “will be good for the development of a real two-party system in Chicago.”

“There are many like him in the new and rapidly growing Negro middle class who would like to run for office and are not yet committed to the Democratic Party,” the Tribune editorial concluded. “Many of the younger college-trained Negroes would turn to the Republican Party if they were given some encouragement and chances for advancement.”

Last hurrah

The Republican Party, however, didn’t endorse Banks as its candidate for 8th Ward alderman. Its choice was Gerald Gibbons, who worked for a printing company and had served as president of the 8th Ward Young Republicans Club.

It was reported that one reason the Republicans didn’t back Banks was because he didn’t vote in the November 1962 general election.

Banks said he would stay in the race as an independent Republican candidate.

“Politics is a strange business,” Banks said to the Tribune. “They try to strike you out before you get a turn at bat. I am in this, with or without the support of the Republican 8th Ward organization. I intend to win.”

Banks campaigned primarily on a promise to promote youth activities in the ward and fight juvenile delinquency. He was critical of incumbent James Condon’s “lack of interest” in the welfare of youths, the Tribune reported.

Condon told voters that during his four years as alderman the 8th Ward got more than $2 million in new street lighting, traffic control signals and street repairs.

On election day, Feb. 26, 1963, Condon retained his 8th Ward seat, finishing first in a field of four with 9,296 votes. The Republican-endorsed candidate, Gerald Gibbons, totaled 4,264. Banks was third with 2,028 votes and an independent with no party affiliation, Coleman Holt, got 1,335.

In recalling the election 50 years later, in 2013, Banks told Bruce Levine of ESPN.com, “Mayor Daley was running the city. Someone asked the mayor where that baseball player was going to finish in the race for the 8th Ward. He said somewhere out in left field. That is where I finished.”

A Tribune columnist noted that, though Banks lost the election, he remained the unofficial mayor of Wrigley Field.

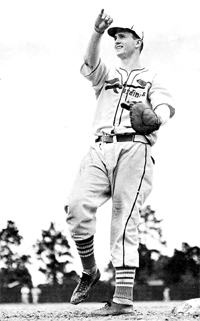

Dean delivered four innings of hitless, scoreless relief and slugged a three-run homer in the bottom of the 10th inning, carrying the Cardinals to a 6-3 triumph over the Reds at St. Louis on Aug. 6, 1935.

Dean delivered four innings of hitless, scoreless relief and slugged a three-run homer in the bottom of the 10th inning, carrying the Cardinals to a 6-3 triumph over the Reds at St. Louis on Aug. 6, 1935. Howerton walked with a limp, earning the nickname Hopalong, but eventually developed into a baseball talent, reaching the big leagues with the Cardinals.

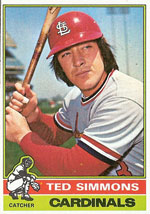

Howerton walked with a limp, earning the nickname Hopalong, but eventually developed into a baseball talent, reaching the big leagues with the Cardinals. Big-league baseball, though, wasn’t hip to the grooves Simmons made in his bats, even though the Cardinals catcher claimed the alterations were done to preserve the lumber, not enhance his hitting.

Big-league baseball, though, wasn’t hip to the grooves Simmons made in his bats, even though the Cardinals catcher claimed the alterations were done to preserve the lumber, not enhance his hitting. Ninety years ago, in June 1935, Alston grabbed an opportunity to play professional baseball, signing a minor-league contract with the Cardinals.

Ninety years ago, in June 1935, Alston grabbed an opportunity to play professional baseball, signing a minor-league contract with the Cardinals. One hundred years ago, on May 30, 1925, Breadon changed managers, replacing Rickey with

One hundred years ago, on May 30, 1925, Breadon changed managers, replacing Rickey with