Seeking a right fielder to complete a lineup counted on to contend for a championship, the Cardinals made a bold move and acquired a good one.

On Nov. 17, 2014, the Cardinals obtained outfielder Jason Heyward and reliever Jordan Walden from the Braves for pitchers Shelby Miller and Tyrell Jenkins. The Cardinals needed a right fielder to replace Oscar Taveras, who died in an auto accident three weeks earlier on Oct. 26.

On Nov. 17, 2014, the Cardinals obtained outfielder Jason Heyward and reliever Jordan Walden from the Braves for pitchers Shelby Miller and Tyrell Jenkins. The Cardinals needed a right fielder to replace Oscar Taveras, who died in an auto accident three weeks earlier on Oct. 26.

As St. Louis Post-Dispatch columnist Bernie Miklasz presciently noted when the deal was made, Heyward was “an elite defender, the best right fielder in baseball (and) should do an effective job of getting on base and energizing the Cardinals’ speed on the bases.”

Nurturing talent

Heyward moved from New Jersey to suburban Atlanta with his family when he was 2. His parents, Eugene and Laura, graduated from Dartmouth. Eugene became an electrical engineer for ITT Technologies, designing electronic warfare systems for Robins Air Force Base, and Laura was an insurance underwriter for Life of Georgia before joining Georgia Power, according to the Atlanta Constitution.

Laura helped Jason develop a love of writing. “He did a writing project on the Negro baseball league in high school,” Laura told the Atlanta newspaper, “and I could see he really had a talent for writing. I thought maybe he could be a sports writer, because you never know if it’s going to work out with baseball. I wanted him to be well-rounded.”

Though his father played basketball at Dartmouth, baseball became Jason’s favorite sport. He began playing the game when he was 5.

Two decades later, when asked by Bernie Miklasz why he preferred baseball to other sports, Heyward said, “It’s the tradition that it holds. It’s the history. It’s timeless … For me growing up, it was just easy to fall in love with it. There’s all the thought that goes into it. The strategy, the cat and mouse games. It’s also a humbling game, because you will fail more times than you succeed and then it becomes all about how you handle it going forward.”

Heyward became a fan of the Braves, who won five National League pennants and a World Series title in the 1990s when he was a youth. After a stellar high school playing career, the Braves made Heyward the first outfielder taken in the opening round of the 2007 amateur draft.

Dazzling debut

A left-handed batter, Heyward was 6-foot-5, 240 pounds and had all the tools. After three seasons in the minors, Baseball America magazine named him the best prospect in the game.

He had a storybook start to his major-league career.

On April 5, 2010, the Braves opened against the Cubs at Atlanta. Heyward was tabbed by manager Bobby Cox to debut in right field and bat seventh.

Braves icon Hank Aaron was there to throw the ceremonial first pitch and Heyward was given the honor of catching the toss.

After delivering the pitch, Aaron offered advice to the rookie. “He said, ‘Have fun. You’re ready to do this,’ ” Heyward told the Atlanta Constitution.

In the opening inning, with the score tied at 3-3, the Braves had two runners on base against Carlos Zambrano, an imposing right-hander.

Zambrano’s first two deliveries to Heyward missed the strike zone and Heyward didn’t bite at either. On the 2-and-0 pitch, Zambrano threw a sinking fastball toward the inner part of the plate. Heyward sent a drive deep into the right-field stands for a three-run home run. Boxscore and Video

Heyward, 20, became the youngest player to hit a homer in his first big-league plate appearance since Ted Tappe, 19, of the Reds did it in 1950. Boxscore

Heyward followed the Opening Day drama with a strong season (.393 on-base percentage and 83 runs scored) and placed second to Giants catcher Buster Posey, whom he competed against in high school, in National League Rookie of the Year Award balloting.

Good as gold

In his first plate appearance on Opening Day in 2011, Heyward again slammed a home run. He joined Kaz Matsui of the (2004-05) Mets as the only other player to hit a homer on Opening Day in his first at-bat in each of his first two seasons. Boxscore

The next year, Heyward slugged 27 homers for the 2012 Braves, scored 93 runs and earned the first of five Gold Glove awards. In a playoff game, he made a leaping grab above the wall in right to deprive the Cardinals’ Yadier Molina. Video and Boxscore

In 2013, Heyward suffered a fractured jaw after being struck by a pitch from Mets left-hander Jon Niese. The next year, Heyward batted .169 versus left-handers and later admitted he wasn’t swinging aggressively against them. His fielding remained spectacular, though. Heyward had the highest number of total chances (375) among National League right fielders and committed one error.

Mix and match

Like Heyward had been for the Braves, the Cardinals had their own highly touted right field prospect, Oscar Taveras, who debuted with them in 2014 and helped bring a division title. Cardinals general manager John Mozeliak said Taveras, 22, would have been the right fielder in 2015. Taveras’ death in an alcohol-related car crash in the Dominican Republic changed that plan.

With Heyward eligible to become a free agent after the 2015 season, the Braves were willing to trade him, and when the Cardinals offered to part with Shelby Miller, 24, who had 15 wins for them in 2013 and 10 in 2014, the deal was made.

Though there was a risk Heyward could leave the Cardinals after one season, Mozeliak told the Post-Dispatch, “We had to look at a way to add an impact player to our club … We’ve said all along we’re focused on 2015.”

Knowing Heyward wore uniform No. 22 with the Braves, Cardinals manager Mike Matheny, who also wore that number, gave it to his new right fielder. When he’d debuted with the Braves, Heyward chose No. 22 in memory of a former high school teammate, Andrew Wilmot, who was killed in a car accident.

Switching sides

On Opening Day for the 2015 Cardinals, Heyward produced three hits, including two doubles, in a win against the Cubs at Wrigley Field. Boxscore

After a slow April (.217 batting mark), he produced consistently well, achieving career highs in hits (160), doubles (33), stolen bases (23) and batting average (.293) and winning a Gold Glove Award. He was successful on 88 percent of his steal attempts (23 of 26). Video

As Heyward’s 2015 season neared its end, Derrick Goold of the Post-Dispatch wrote, “He’s the best defensive right fielder in the majors … He’s exceptional with his glove, precise with fundamentals and takes extra bases.”

The 2015 Cardinals finished with the best record (100-62) in the majors. Their reward: a matchup in the fall tournament with the third-place finisher in their division _ the Cubs. Heyward batted .357 in the series, but the Cubs prevailed. Then they stung the Cardinals again, signing Heyward to an eight-year $184 million contract.

In explaining why he went to the Cubs, even though the Cardinals’ offer was greater in guaranteed value and more overall money, Heyward said he saw Chicago as more of the up-and-coming franchise.

“You have to look at age, you have to look at how fast the (Cardinals) team is changing and how soon those changes may come about,” Heyward told the Chicago Tribune. “You have Yadier (Molina), who is going to be done in two years, maybe. You have Matt Holliday, who is probably going to be done soon … (Adam) Wainwright is probably going to be done in three or four years … I felt like if I was to look up in three years and see a completely different (Cardinals) team, that would kind of be difficult. Chicago really offers an opportunity to come into the culture and be introduced to the culture by a young group of guys.”

The Cubs further strengthened themselves, while weakening the Cardinals, by signing free-agent pitcher John Lackey, who won 13 for St. Louis in 2015. Reacting to the defections of two prominent Cardinals to the Cubs, Tribune columnist David Haugh wrote, “What’s next, a Mike Shannon Grill in Wrigleyville?”

Heyward was correct about the Cubs being on the rise. In 2016, his first season with them, the Cubs became World Series champions for the first time since 1908.

Heyward won another Gold Glove Award with the 2016 Cubs but he batted .230 with a mere seven home runs. In the World Series versus Cleveland, he had no RBI, scored no runs and batted .150.

In seven seasons with Chicago, Heyward batted .245. The Cubs released him in November 2022. According to the Tribune, the Cubs were on the hook to pay him $22 million for 2023, the final year of the eight-year contract. Heyward also was to get four $5 million installments from 2024 through 2027 as part of his initial signing bonus with Chicago.

In October 1964, Joe Becker joined the Cardinals as pitching coach on the staff of newly appointed manager Red Schoendienst.

In October 1964, Joe Becker joined the Cardinals as pitching coach on the staff of newly appointed manager Red Schoendienst. Pitts was a player, manager, coach and instructor in the minors, primarily with the Cardinals.

Pitts was a player, manager, coach and instructor in the minors, primarily with the Cardinals. Making a leap from the Class A level of the minors to the big leagues, Rose won the starting second base spot with the Reds at 1963 spring training. Once the season began, the player who would become baseball’s all-time hits king looked feeble at the plate.

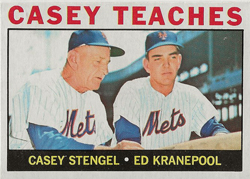

Making a leap from the Class A level of the minors to the big leagues, Rose won the starting second base spot with the Reds at 1963 spring training. Once the season began, the player who would become baseball’s all-time hits king looked feeble at the plate. Ed Kranepool was the teen Stengel started that day, putting him in the No. 3 spot in the order ahead of cleanup hitter and future Hall of Famer Duke Snider.

Ed Kranepool was the teen Stengel started that day, putting him in the No. 3 spot in the order ahead of cleanup hitter and future Hall of Famer Duke Snider. On Oct. 2, 1974, the Pirates’ Bob Robertson swung and missed at strike three, a strikeout that should have ended the game. A Cubs win would have kept alive the Cardinals’ division title hopes.

On Oct. 2, 1974, the Pirates’ Bob Robertson swung and missed at strike three, a strikeout that should have ended the game. A Cubs win would have kept alive the Cardinals’ division title hopes.