The Milwaukee Braves looked at Joey Jay and saw a problem pitcher. Fred Hutchinson looked at him and saw an ace.

A right-hander, Jay became the first former Little League player to reach the majors when he joined the Braves out of high school at 17 in 1953.

A right-hander, Jay became the first former Little League player to reach the majors when he joined the Braves out of high school at 17 in 1953.

At 6-foot-4, 225 pounds, Jay looked like a man but acted like a boy. He was immature, got labeled a spoiled kid and the Braves were reluctant to pitch him.

Fred Hutchinson, when he managed the Cardinals, got a look at what Jay was capable of accomplishing. In 1958, Jay, who had seven wins that year as a fill-in starter, was 3-1 with an 0.86 ERA versus the Cardinals.

Two years later, when Hutchinson was Cincinnati manager, the Reds acquired Jay at Hutchinson’s urging and he prospered, achieving consecutive 21-win seasons and helping the club become 1961 National League champions.

Not ready for prime time

As a Little Leaguer in Connecticut, Jay played first base. He was a pitcher in high school. Multiple pro teams were interested, including the Pirates. Jay met with their general manager, Branch Rickey, but accepted a $40,000 bonus from the Braves, in part, because his summer league coach was a Milwaukee scout, according to Sports Illustrated.

Because of the bonus amount, Jay was required under baseball rules then to be on the Braves’ roster for two full years before he could be sent to the minors.

The teen didn’t receive much of a welcome when he joined the Braves in June 1953. He rarely pitched and manager Charlie Grimm “never said two words to me,” Jay told The Sporting News.

According to Sports Illustrated’s Walter Bingham, “Jay quickly won himself a reputation as an eater and sleeper of championship caliber. He seldom was seen awake without a candy bar or a soft drink, often with both. He would eat in the bullpen during games. At one point, he weighed 245 pounds, which, even at his height, made him look fat.

“On his first trip with the Braves, he overslept one day and arrived at the park 20 minutes before game time. Some of the older players, who resented bonus players anyway, didn’t let Jay forget it. Another time, Jay fell asleep on the bus coming back from Ebbets Field. When the bus arrived at the hotel, all the players tiptoed off and the bus driver drove away still carrying Jay, fast asleep.”

Jay pitched 10 innings for the 1953 Braves and didn’t allow a run, but he was unhappy. “I felt I was a burden on the club,” he told The Sporting News. “My dad finally talked me out of quitting.”

The following year, he totaled 18 innings for the 1954 Braves and then 19 innings for the 1955 club before being sent to Toledo. Jay was in the minors in 1956 and for most of 1957.

“He hadn’t grown up,” Ben Geraghty, who managed Jay with Wichita in 1957, told Sports Illustrated. “He had an awful temper.”

One day, Jay got mad during a game, sulked and began lobbing pitches. Afterward, Geraghty said to him during a team meeting “that if he didn’t have the guts to act like a man, he could clear out,” Sports Illustrated reported.

Jolted, Jay went on to post a 17-10 record for Wichita.

Looking good

Jay, 22, began the 1958 season in the Braves’ bullpen, struggled (9.00 ERA in four appearances) and was “the lowest-ranking” of the club’s relievers, according to The Sporting News.

When starter Bob Buhl went on the disabled list in May because of elbow pain, Gene Conley replaced him but disappointed.

In desperation, manager Fred Haney started Jay on June 13 at St. Louis. He held the Cardinals scoreless and got the win in a game shortened to six innings because of rain.

“Stan Musial (0-for-2 with a walk) praised Jay” for showing the ability “to get over his good fastball, curve, changeup and slider,” the St. Louis Post-Dispatch reported. Boxscore

Nine days later, matched against Sal Maglie, Jay was a hard-luck loser in a 2-1 Cardinals triumph, but his impressive pitching in two starts versus St. Louis convinced Haney to keep him in the rotation. Boxscore

“He has the confidence to throw his best curve at two balls and no strikes,” Braves catcher Del Crandall told Sports Illustrated.

In seven July starts for the 1958 Braves, Jay was 5-2 with a 1.39 ERA. Two of those wins came against the Cardinals _ a four-hitter to beat Maglie at St. Louis on July 15, and a two-hit shutout at Milwaukee a week later. Boxscore and Boxscore

“There isn’t a better pitcher in our league right now,” Braves coach Whit Wyatt said to The Sporting News.

The good vibes didn’t last long, though. Jay pulled a tendon in his right elbow and was limited to 11 innings in August. Then, in his lone September appearance, a relief stint against the Cardinals, he fractured his left ring finger when he knocked down a hard grounder from Irv Noren. Boxscore

Milwaukee won the pennant but didn’t include Jay (7-5, 2.14 ERA) on the World Series roster.

Change of scenery

Jay regressed in 1959 (6-11, 4.09 ERA). “He just won’t do anything in pregame drills,” Haney complained to Sports Illustrated. “He’s fat and he’s too lazy to get in shape.” In 1960, he was 9-8.

Fred Hutchinson, fired by the Cardinals near the end of the 1958 season, became Reds manager in July 1959 and needed pitchers. The Reds allowed the most runs in the National League in 1959 and the second-most in 1960.

Hutchinson and Braves pitcher Lew Burdette had homes on Anna Maria Island in Florida and attended cookouts together. Hutchinson asked Burdette about Jay and Burdette recommended him, Jay told the Cincinnati Enquirer.

In December 1960, the Reds dealt shortstop Roy McMillan to the Braves for Jay and Juan Pizarro. (Pizzaro was flipped to the White Sox for third baseman Gene Freese, who played for Hutchinson with the Cardinals.)

Jay got off to a shaky start in his Reds debut at St. Louis. In the first inning, after he gave up two runs, he walked a batter to load the bases with two outs. Jay expected to be lifted when Hutchinson came to the mound. Instead, the manager challenged him: “Don’t walk yourself out of there. Make them knock you out.”

As author Doug Wilson noted in a book about Hutchinson, “Jay, surprised and grateful, pitched his way out of the jam. Jay lost his first three decisions in 1961 but his manager stuck with him. Jay responded to this confidence by turning into one of the best pitchers in the league.” Boxscore

“That’s all I did for him: Let him pitch,” Hutchinson told The Sporting News.

Joining a rotation with Jim O’Toole and Bob Purkey, Jay helped transform the Reds’ pitching staff from one of the worst in the league to the best.

In his book “Pennant Race,” reliever Jim Brosnan recalled how during a clubhouse meeting at Pittsburgh a confident Jay held a scorecard in one hand and a cigar in the other while going over the Pirates’ batters. After the game, which Jay won, he sat next to Brosnan on the bus ride to the airport and puffed on a pipe.

“You always smoke a pipe when you win?” Brosnan asked him. “Usually you got a cigar in your mouth.”

“Pipe relaxes me,” Jay replied. “You should try one.”

Jay still packed on the pounds _ “I’m about 12 jelly rolls and 15 cream puffs too heavy,” he told Brosnan. “I buy them for the kids, then eat them myself” _ but was fattening up on wins, too. He led the league in wins (21) and shutouts (four) as the 1961 Reds (93-61) won a pennant for the first time in 21 years.

In the World Series against the Yankees, Jay got the Reds’ only win _ a four-hitter in Game 2. Video and Boxscore

Ups and downs

Jay won 21 again in 1962, though he was 0-3 versus the Cardinals. The 1962 Reds (98-64) totaled five more wins than they did in their championship season, but finished in third place.

On the final day of the 1963 season, Stan Musial played his last game for the Cardinals and exited after getting a pair of singles against Jim Maloney. The Cardinals won in the 14th on Dal Maxvill’s RBI-double versus Jay. He lost 18 that season, including all four decisions against the Cardinals. Boxscore

Jay was involved in another noteworthy game on the last day of the 1964 season. The Cardinals and Reds entered the day tied for first place.

At Cincinnati, Jay relieved in the fifth with one out, two on and the Phillies ahead, 4-0, and got Tony Taylor to ground into a double play. In the sixth, however, Jay gave up a two-run single to Tony Gonzalez and a three-run homer to Dick Allen. The Phillies won, 10-0, enabling the Cardinals to secure the pennant when they beat the Mets. Boxscore

In spring 1966, Cardinals general manager Bob Howsam agreed to trade Nelson Briles, Steve Carlton, Phil Gagliano and Mike Shannon to the Reds for Leo Cardenas, Gordy Coleman and Jay, but the deal was blocked by Cardinals upper management, The Sporting News reported.

Soon after, in June 1966, Jay was dealt to the Atlanta Braves and he completed his career with them that season.

Jay was 99-91 in the majors. Willie Mays batted .200 (8-for-40) against him and Stan Musial was at .208 (10-for-48).

In his autobiography, Musial said of Jay, “Fred Hutchinson gave him confidence and a good talking-to. At Milwaukee, Jay struck me as having pretty good stuff … but he threw a lot of slow curves and wasted his fastball. When the Reds got him, Hutchinson … made him throw that good fastball for strikes.”

One of May’s nicknames was The Dude. He got it, the Baltimore Sun noted, because of “his funky wardrobe” and “unflappable optimism.”

One of May’s nicknames was The Dude. He got it, the Baltimore Sun noted, because of “his funky wardrobe” and “unflappable optimism.”

Making a leap from the Class A level of the minors to the big leagues, Rose won the starting second base spot with the Reds at 1963 spring training. Once the season began, the player who would become baseball’s all-time hits king looked feeble at the plate.

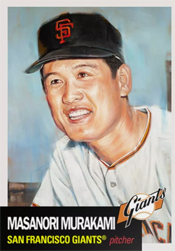

Making a leap from the Class A level of the minors to the big leagues, Rose won the starting second base spot with the Reds at 1963 spring training. Once the season began, the player who would become baseball’s all-time hits king looked feeble at the plate. On Sept. 1, 1964, Masanori Murakami, 20, became the first Japanese native to play in the big leagues when he pitched in relief for the Giants against the Mets.

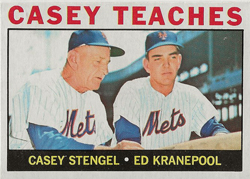

On Sept. 1, 1964, Masanori Murakami, 20, became the first Japanese native to play in the big leagues when he pitched in relief for the Giants against the Mets. Ed Kranepool was the teen Stengel started that day, putting him in the No. 3 spot in the order ahead of cleanup hitter and future Hall of Famer Duke Snider.

Ed Kranepool was the teen Stengel started that day, putting him in the No. 3 spot in the order ahead of cleanup hitter and future Hall of Famer Duke Snider.