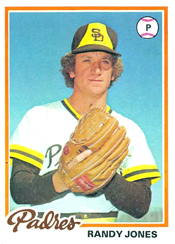

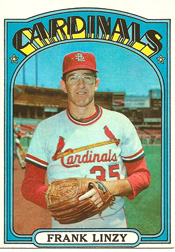

A right-handed sinkerball specialist, Frank Linzy pitched for and against the Cardinals. During his prime, as a Giants reliever, some of his most noteworthy achievements came versus St. Louis. He was on the backside of his career when he joined the Cardinals in 1970.

In 11 seasons with the Giants (1963, 1965-70), Cardinals (1970-71), Brewers (1972-73) and Phillies (1974), Linzy totaled 110 saves, 62 wins and a 2.85 ERA. He led the Giants in saves for five years in a row (1965-69). “The first five years were fun,” Linzy told the Tulsa World. “The next five were a struggle.”

In 11 seasons with the Giants (1963, 1965-70), Cardinals (1970-71), Brewers (1972-73) and Phillies (1974), Linzy totaled 110 saves, 62 wins and a 2.85 ERA. He led the Giants in saves for five years in a row (1965-69). “The first five years were fun,” Linzy told the Tulsa World. “The next five were a struggle.”

Country boy

Linzy was born “out in the bushes” near Fort Gibson, Okla., according to the Tulsa newspaper. His father farmed cotton and soy beans. The family moved to Porter, Okla., when Frank was 5. One of his boyhood friends was Jim Brewer, who, like Linzy, would become a relief pitcher in the majors. “Jim and I played basketball under the street lights by the hour,” Linzy recalled to the Tulsa World.

While in school, Linzy helped his father chop cotton. He also played baseball and basketball, fished for crappie and hunted for quail. Linzy developed into a standout baseball and basketball player at Porter High School. As a senior, he averaged 20 points per game in basketball and posted a 12-2 pitching record.

The Reds offered him a $10,000 bonus, according to Bob Broeg of the St. Louis Post-Dispatch, but Linzy instead took a basketball scholarship offer from famed coach Hank Iba at Oklahoma State. He lasted one semester. “I couldn’t make my grades,” Linzy told the Tulsa World. “I never studied before. I took recess more than anything else (in high school) and they didn’t have recess (in college).”

Linzy tried another semester at Northeastern State in Tahlequah, Okla., then returned home. He was playing baseball for a town team when offered a contract (but no signing bonus) from Giants scout Bully McLean, a former minor-league outfielder with the Chickasha Chicks and Henryetta Hens.

The Giants assigned Linzy to a farm club in Salem, Va., in July 1960. He wanted to be an outfielder because his favorite player was Duke Snider, but Salem manager Jodie Phipps, a former Cardinals prospect who totaled 275 wins in 19 seasons as a minor-league pitcher, told Linzy he’d do better on the mound.

As a starting pitcher, Linzy advanced through the Giants’ system. With Springfield (Mass.) in 1963, he was 16-6 with a 1.55 ERA. Impressed, the Giants called him to the majors in August 1963 and he joined them on the road.

“All I had were Levis and just plain old shirts, and I walked into the hotel lobby and there’s all these guys with sport coats on and dress pants,” Linzy recalled to the Tulsa World. “The only time I felt equal was when we were on the baseball field and I had the same kind of clothes on as they did.”

Super sinker

Linzy made his Giants debut in a start against the Reds. (One of just two starts in 516 big-league appearances.) He struck out the first batter he faced, Pete Rose. In his second appearance, against the Cardinals, Linzy came in with the bases loaded, one out, and fanned Bill White, then got Stan Musial to pop out. In Linzy’s third game, he struck out Hank Aaron. Boxscore Boxscore Boxscore

After another season in the minors, Linzy stuck with the Giants in 1965, beginning his five-year run as their closer.

Linzy threw two pitches _ a heavy sinker and hard slider. “I didn’t have enough pitches,” he said to the Tulsa World. “That’s why I couldn’t have been a starter.”

The sinker was his specialty. Linzy said he gripped the slick part of the ball rather than the seams to make it spin. Catcher Ed Bailey told the San Francisco Examiner, “He’s holding an overlap grip with a back reverse and a flat flipper finger.” Or, as Linzy’s fellow pitcher, Bobby Bolin, put it, “The backspin on the ball, overlapping with the downspin, makes it sink.”

Linzy focused on getting grounders instead of strikeouts. He was durable and effective, but also “I was scared to death,” he told the Post-Dispatch. “… I could throw crooked. That’s about all I can say for what I did.”

Asked to describe the keys to being a reliever, he told the Tulsa newspaper, “You’ve got to have a strong back and a weak mind.”

Linzy earned his first big-league win on May 5, 1965, with two scoreless innings at St. Louis. Two months later, he got his first hit _ a home run into the wind at Candlestick Park versus the Cardinals’ Ray Washburn. “I’m strong enough to hit the ball out,” Linzy told the Examiner. “I just never connect.” Later in the game, he lined a single against Ray Sadecki. Boxscore Boxscore

Linzy was 3-0 with two saves and a 1.08 ERA versus the 1965 Cardinals. Overall for the season, he won nine and converted 20 of 25 save chances.

The Cardinals were a club Linzy continued to do well against. For his career, he was 5-2 with nine saves and 1.65 ERA versus St. Louis. He never gave up a home to a Cardinals batter. In 1967, when the Cardinals were World Series champions, Linzy pitched 9.2 scoreless innings against them. When the Cardinals repeated as National League champions in 1968, Linzy faced them over 11.1 innings and posted an 0.79 ERA.

Career batting averages against Linzy among players on Cardinals championship clubs included Orlando Cepeda (.105), Ken Boyer (.167), Dick Groat (.143), Julian Javier (.167), Roger Maris (.000), Tim McCarver (.192) and Mike Shannon (.182).

Ups and downs

Linzy bought a 10-acre spread across a gravel road from his father-in-law’s cattle ranch near Coweta, Okla. The pitcher spent winters picking pecans from the trees on his property. Before heading to spring training in 1969, Linzy laid the foundation for his house. Using a blueprint he sketched on cardboard, his in-laws built Linzy and his wife their brick dream house, the Tulsa World reported.

Though he had 14 wins for the 1969 Giants, Linzy converted only 52 percent of his save chances. His sinker too often was staying up in the strike zone. Linzy noticed his right arm lacked the elasticity of his best seasons.

He looked terrible with the 1970 Giants (7.01 ERA in 25.2 innings), but the Cardinals, desperate for quality relievers, decided to take a chance. On May 19, 1970, the Giants sent Linzy to the Cardinals for pitcher Jerry Johnson.

The Cardinals hoped Linzy’s sinker would induce ground ball outs on their new artificial surface, but batters had other ideas. Linzy posted a 4.08 ERA in home games for the 1970 Cardinals. In 47 games overall for them that year, he walked more than he fanned and gave up more hits than innings pitched. Right-handed batters hit .298 against him.

Brought back by the Cardinals in 1971, Linzy rewarded them with a return to form early in the season. In April, he was 1-0 with three saves and a 1.88 ERA. He added two more saves in May, allowing no earned runs for the month.

On June 9, 1971, with his ERA for the season at 2.10, Linzy collided with first baseman Bob Burda as both pursued a ball bunted by the Braves’ Ralph Garr. Linzy suffered multiple fractures of the left cheekbone. Boxscore

The Cardinals swooned in June, with an 8-21 record for the month, and got only one save (from Don Shaw) during the nearly 30 days Linzy was sidelined.

After his return, Linzy pitched in 25 games but didn’t get many save chances. He finished the season with six saves, four wins and a 2.12 ERA. In 23 home games covering 30 innings, his ERA was 1.50. Overall, batters hit .226 against him in 1971, but he allowed 48 percent of inherited runners to score.

Dealt to the Brewers in March 1972 for pitching prospect Richard Stonum, Linzy spent two seasons with Milwaukee (totaling 25 saves) and one with the Phillies.

“I played as hard as I could as long as I could,” Linzy told the Tulsa World. “I didn’t ever quit. They just sent me home.”

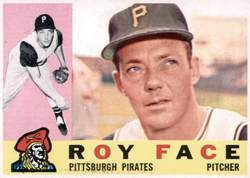

In his book “Stan Musial: The Man’s Own Story,” the Cardinals standout named Face the relief pitcher on his all-time team of players he saw during his 22 years in the majors.

In his book “Stan Musial: The Man’s Own Story,” the Cardinals standout named Face the relief pitcher on his all-time team of players he saw during his 22 years in the majors.

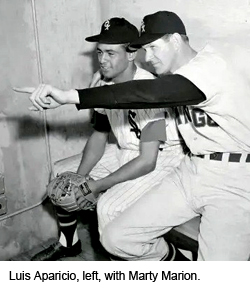

Marty Marion was the White Sox manager who brought Aparicio to the major leagues and made him the starting shortstop as a rookie in 1956.

Marty Marion was the White Sox manager who brought Aparicio to the major leagues and made him the starting shortstop as a rookie in 1956. A left-hander with a stellar fastball he couldn’t control, Lolich, 21, was an unhappy prospect in the Tigers system when he was dispatched to Portland (Ore.) in 1962. The pitching coach there,

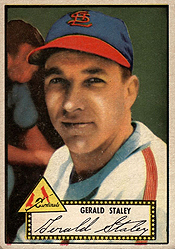

A left-hander with a stellar fastball he couldn’t control, Lolich, 21, was an unhappy prospect in the Tigers system when he was dispatched to Portland (Ore.) in 1962. The pitching coach there,  When he was with a Cardinals farm club in 1947, Staley was throwing warmup tosses to infielder Julius Schoendienst, brother of St. Louis second baseman Red Schoendienst. “He noticed I had a natural sinker when I threw three-quarters overhand,” Staley recalled to United Press International. “He said my sinker did more than my fastball. So I stuck with it.”

When he was with a Cardinals farm club in 1947, Staley was throwing warmup tosses to infielder Julius Schoendienst, brother of St. Louis second baseman Red Schoendienst. “He noticed I had a natural sinker when I threw three-quarters overhand,” Staley recalled to United Press International. “He said my sinker did more than my fastball. So I stuck with it.”