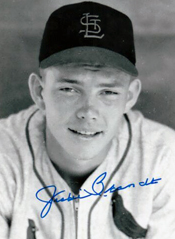

Danny Cox began the 1983 baseball season in the low level of the minors and ended it as a member of the starting rotation of the reigning World Series champion Cardinals.

Matched against Steve Carlton and facing a lineup with Pete Rose, Joe Morgan and Mike Schmidt, Cox pitched 10 scoreless innings versus the Phillies in his big-league debut on Aug. 6, 1983.

Matched against Steve Carlton and facing a lineup with Pete Rose, Joe Morgan and Mike Schmidt, Cox pitched 10 scoreless innings versus the Phillies in his big-league debut on Aug. 6, 1983.

The stellar performance didn’t get Cox a win, though. That came a couple of weeks later when he opposed another future Hall of Fame pitcher, Nolan Ryan.

Fun in Florida

A right-hander attending Troy University, Cox, 21, was chosen by the Cardinals in the 13th round of the 1981 amateur draft, a couple of picks after the Mets took a high school outfielder, Lenny Dykstra, in the same round.

Cox pitched for a rookie team and a Class A club his first two seasons in the Cardinals’ farm system. Then in 1983, he was assigned to rookie manager Jim Riggleman’s Class A team, the St. Petersburg Cardinals. Even at that level, Cox was matched against an exceptional pitching opponent.

After losing his first two decisions in 1983, Cox, 23, started on May 12 at home against the Fort Myers Royals. Their starter, Bret Saberhagen, 19, was in his first season of professional ball. (Two years later, Saberhagen received the first of his two American League Cy Young awards with the Kansas City Royals.)

Pitching before 882 spectators at Al Lang Stadium in St. Petersburg, Cox threw a four-hitter in a 2-1 victory. Saberhagen went six innings and allowed both runs.

Facing a Fort Myers lineup that included future big-leaguers Mike Kingery and Bill Pecota, Cox retired the last 11 batters in a row. “He dominated,” St. Petersburg catcher Barry Sayler told the St. Petersburg Times. “He was working the inside of the plate, mixed his fastball and slider, and threw hard.”

Cox credited the advice he received from St. Petersburg teammate and closer Mark Riggins (who went on to become pitching coach of the St. Louis Cardinals, Chicago Cubs and Cincinnati Reds). “I started off throwing my fastball inside, and then Mark Riggins told me to take a little off my slider and mess up their timing,” Cox said to the St. Petersburg Times. “I was wanting to win real bad.”

Five days later, in a rematch at Fort Myers, Cox, with relief help from Riggins, again beat Saberhagen in a 7-2 St. Petersburg triumph.

On the rise

After five starts for St. Petersburg (2-2, 2.53 ERA), Cox was promoted to Class AA Arkansas. Playing for manager Nick Leyva, Cox was 8-3 with a 2.29 ERA in 11 starts. In July, he got promoted again, to manager Jim Fregosi’s Class AAA Louisville club. Cox made two starts for Louisville and pitched well (2.45 ERA).

Then came a special audition. The St. Louis Cardinals chose him to start against the Baltimore Orioles in the Baseball Hall of Fame exhibition game at Cooperstown, N.Y., on Aug. 1.

The Orioles, on their way to an American League pennant and World Series championship in 1983, were limited to three hits and no runs in the six innings Cox worked against them. “He was very impressive,” Cardinals manager Whitey Herzog said to the St. Louis Post-Dispatch.

Herzog wanted to see more. The Cardinals put Cox on their roster. His next start came in a big-league game against the Phillies.

Tough task

Cox’s debut assignment was daunting. The opposing starter, Steve Carlton, had dominated the Cardinals since being traded by them to the Phillies in 1972.

The matchup was intriguing for other reasons as well:

_ Chase Riddle, head coach of Troy’s baseball team when Cox pitched there, was the Cardinals scout who signed Carlton two decades earlier.

_ Like Cox, Carlton also impressed the Cardinals by pitching well in a Hall of Fame exhibition game. On July 25, 1966, Carlton, 21, was at Class AAA Tulsa when the Cardinals chose him to start against the Minnesota Twins in the Cooperstown exhibition. Carlton pitched a complete game, striking out nine, and was the winning pitcher. He never went back to the minors.

Carlton and Cox engaged in a mighty duel. The ace was in top form, pitching nine scoreless innings. The newcomer matched him, then surpassed him, pitching a scoreless 10th after Carlton was relieved by Al Holland.

Cox “didn’t look like a rookie to me,” Joe Morgan told the Associated Press. “I was really impressed by the way he located his pitches and hit the corners.”

Phillies manager Paul Owens said to the Philadelphia Inquirer, “He moved the ball around and threw strikes. That kid was excellent.”

Bruce Sutter, who hadn’t pitched in a week because of the funeral of his father, took over for Cox in the 11th and gave up a run. The 1-0 victory moved the Phillies ahead of the Pirates and into first place in the National League East.

“That was a World Series type of game,” Owens told the Inquirer. “Nobody even left the park.”

Morgan said, “These are the games that win pennants.”

Indeed, the Phillies went on to become National League champions in 1983. Boxscore

Sweet win

In his next start, Cox gave up a grand slam to ex-Cardinal Leon Durham and was beaten by the Cubs. Boxscore

His first win came in his fourth start on Aug, 21. Matched against Nolan Ryan and the Astros, Cox prevailed in a 5-2 Cardinals victory. Cox pitched 7.2 innings and allowed two runs. Ryan surrendered five runs in six innings. Cox also got his first big-league hit in that game, a single against Ryan in a two-run sixth. Boxscore

Cox made 12 starts for the 1983 Cardinals and was 3-6 with a 3.25 ERA. He pitched a total of 218 innings _ 129.1 in the minors, 83 with the Cardinals and another six in the Hall of Fame exhibition game.

Money ball

Two years later, Cox had his best year in the majors. He was 18-9 for the Cardinals during the 1985 regular season, flirted with a perfect game bid against the Reds, and won Game 3 of the National League Championship Series versus the Dodgers.

The 1985 World Series matched Cox and the Cardinals against Bret Saberhagen and the Royals. In starts against Joaquin Andujar and John Tudor, Saberhagen beat the Cardinals twice, including Game 7, and was named most valuable player of the World Series. Cox was just as good but not as fortunate. He started Games 2 and 6, allowed just two runs in 14 total innings, but didn’t get a decision in either game.

Cox helped the Cardinals win another pennant in 1987. He shut out the Giants in Game 7 of the National League Championship Series. Video

In the World Series versus the Twins, Cox won Game 5, beating Bert Blyleven, but was the losing pitcher in relief of Joe Magrane in Game 7.

In six seasons with St. Louis, Cox was 56-56. As a reliever with the 1993 Blue Jays, he got to be part of a World Series championship club.

Duke Carmel certainly fit the part. He was named after Duke Snider, had the mannerisms of Ted Williams and could hit with the power of Mickey Mantle.

Duke Carmel certainly fit the part. He was named after Duke Snider, had the mannerisms of Ted Williams and could hit with the power of Mickey Mantle.

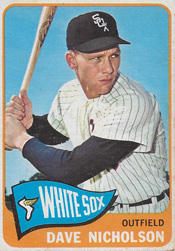

In January 1958, Nicholson was 18 when he signed with the Orioles for more than $100,000, a shocking sum for an amateur at that time.

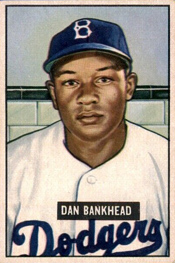

In January 1958, Nicholson was 18 when he signed with the Orioles for more than $100,000, a shocking sum for an amateur at that time. In August 1947, Bankhead debuted for the Dodgers against the Pirates. His second appearance came against the Cardinals.

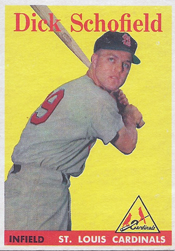

In August 1947, Bankhead debuted for the Dodgers against the Pirates. His second appearance came against the Cardinals. He helped the Pirates, Dodgers and Cardinals win National League pennants. He played 19 seasons in the majors. He was the second of four generations in his family to play pro baseball.

He helped the Pirates, Dodgers and Cardinals win National League pennants. He played 19 seasons in the majors. He was the second of four generations in his family to play pro baseball.