Though it is a franchise that has benefitted from hitters the likes of Stan Musial, Rogers Hornsby, Albert Pujols, Lou Brock and Enos Slaughter, the Cardinals have had only one player achieve 20 doubles, 20 triples and 20 home runs in a season: Jim Bottomley.

A left-handed batter whose stroke regularly produced highly elevated line drives, Bottomley totaled 42 doubles, 20 triples and 31 home runs in 1928, the year he earned the National League Most Valuable Player Award and helped the Cardinals win their second pennant.

A left-handed batter whose stroke regularly produced highly elevated line drives, Bottomley totaled 42 doubles, 20 triples and 31 home runs in 1928, the year he earned the National League Most Valuable Player Award and helped the Cardinals win their second pennant.

Bottomley is one of seven players in the 20-20-20 club. The others are Frank Schulte (1911 Cubs), Jeff Heath (1941 Indians), Willie Mays (1957 Giants), George Brett (1979 Royals), Curtis Granderson (2007 Tigers) and Jimmy Rollins (2007 Phillies). Schulte, Mays, Granderson and Rollins also had 20 stolen bases in the seasons in which they produced 20 doubles, 20 triples and 20 home runs.

Finding his footing

In 1916, when Bottomley was 16, he quit high school in Nokomis (Ill.) and worked as a truck driver, grocery clerk, railroad clerk and blacksmith’s apprentice while also playing semipro baseball, according to the Associated Press. His father and brother were coal miners. The brother was killed in a mine accident.

“I know how hard that kind of work was on my father and how much my mother worried about it,” Bottomley later told The Sporting News. “When I went into baseball, it was a choice of making good at that or returning to the mines. It hardly was any choice at all.”

A policeman saw Bottomley hit two home runs and three triples in a local game and told Cardinals manager Branch Rickey he should give Bottomley a look. In the meantime, Bottomley wrote to Rickey and asked for a tryout. Cardinals scout Charley Barrett was sent to watch Bottomley play and was impressed.

In early fall of 1919, Bottomley, 19, was summoned to St. Louis so that Rickey could see him perform. Rickey sought prospects for the farm system he was starting to build.

Bottomley’s introduction to the big city was expensive. Unsure how to get to Robison Field, he hailed a taxi when he arrived at the bus station. The driver charged him more than $4 to go to the ballpark, according to the Brooklyn Eagle.

When Bottomley reported to the field, Rickey hardly could believe what he saw. The first baseman wore shoes half a dozen sizes too large for him. The shoes curled up at the toes and had spikes nailed to the front. The Brooklyn Eagle described them as Charlie Chaplin clown shoes. Bottomley tripped over the bag, falling on his face and then on his back.

“I told Charley Barrett this fellow could never do it because his feet were too big,” Rickey recalled to the Brooklyn newspaper, “but Barrett declared his feet were all right. It was that pair of shoes.”

In the book “The Spirit of St. Louis,” Rickey said, “Bottomley, properly shod, had the grace and reflexes of a great performer.”

The Cardinals signed Bottomley for $150 a month and arranged for him to report to the minors in 1920.

Man of the people

Bottomley gave the Cardinals a big return on their modest investment. Called up to the majors in August 1922, he became their first baseman. He hit .371 in 1923 and the next year drove in 12 runs in a game against the Dodgers. Boxscore

Using a choked grip on a heavy bat, Bottomley drove in more than 110 runs six seasons in a row (1924-29), and hit better than .300 in nine of his 11 years with the Cardinals. (In the other two years, he hit .299 and .296.)

When he was Cardinals manager, Rogers Hornsby told United Press, “I’d rather see Jim Bottomley at the plate when a run is badly needed than any other player I could name.”

Bottomley “was the best clutch hitter I ever saw,” Hall of Famer Frankie Frisch said to the New York Times.

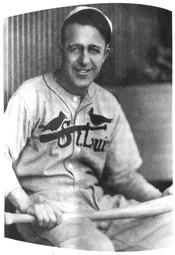

Nicknamed Sunny Jim _ “He has a disposition that refuses to see the gray outside of the clouds of life,” Harold Burr of the Brooklyn Eagle noted _ Bottomley was a fan favorite, especially with the Knothole Gang kids and the Ladies Day crowds.

“Cap perched jauntily over his left eye, the smiling Bottomley walked with a slow swagger that was as much a trademark as his heavy hitting,” Bob Broeg of the St. Louis Post-Dispatch noted.

Bottomley was a bachelor during his playing days with the Cardinals. (In 1933, he married Betty Brawner, who operated a beauty salon in the Missouri Theater building in St. Louis.) Cardinals bachelors stayed at a hotel in the West End of St. Louis during Bottomley’s time. According to The Sporting News, “There every night you could see Jim and his cohorts seated in chairs out in front of the hotel, holding court with the fans.”

Gold standard

Of Bottomley’s 187 hits in 1928, roughly half (93) were for extra bases. His 362 total bases led the league.

Dodgers pitcher Rube Ehrhardt told the Brooklyn Eagle, “Bottomley is a great slugger … He pulls a ball to right field by a combination of strength, wrist snap and perfect timing.”

By June 1928, Bottomley had his 20th double of the season, and his 20th homer came the next month. All he needed were 20 triples to become baseball’s second 20-20-20 player. Entering September with 14 triples, Bottomley made his run for the mark.

He hit a triple at Cincinnati on Sept. 2, then got triples in three consecutive home games _ Sept. 9 versus the Pirates and Sept. 10-11 against the Reds. His 19th triple came Sept. 22 at the Polo Grounds versus the Giants.

On Sept. 29 at Boston, the Cardinals went into the next-to-last game of the season with a 94-58 record, two games ahead of the Giants (92-60). A win would clinch the pennant.

Leading off the game for the Cardinals, Taylor Douthit hit a slow roller to second. Braves player-manager Rogers Hornsby tried to scoop it, but the ball trickled between his legs and into right field for a two-base error. After a Frankie Frisch single scored Douthit, Bottomley drove a pitch from ex-Cardinals teammate Art Delaney into right-center. Eddie Brown, the center fielder, reached for it, but the ball caromed off his glove and hit the bleacher wall. Frisch scored and Bottomley streaked into third with his 20th triple. Chick Hafey followed with a sacrifice fly, scoring Bottomley, and the Cardinals went on to a 3-1 pennant-clinching win. Boxscore

For the season, Bottomley hit .325, scored 123 runs and drove in 136. He had a .402 on-base mark and a .628 slugging percentage. Bottomley batted .359 with runners in scoring position.

“Bottomley is the Lou Gehrig type _ a hustler, carefree, great in the pinches,” Yankees pitcher Waite Hoyt told North American Newspaper Alliance.

(Bottomley clouted a home run versus Hoyt in Game 1 of the 1928 World Series at Yankee Stadium. He also was credited with a triple in Game 3 at St. Louis when Yankees center fielder Cedric Durst took several steps toward the ball, then futilely tried to turn back as it sailed over his head. Boxscore)

For being named National League MVP by the Baseball Writers Association of America, league president John Heydler awarded Bottomley $1,000 in gold.

The league and the Cardinals arranged for the prize to be given before a game against the Phillies at St. Louis on June 8, 1929. Because of Bottomley’s popularity with youngsters, Cardinals owner Sam Breadon invited girls and boys of school age to attend the Saturday afternoon game for free.

A total of 12,806 youths _ 9,643 boys and 3,163 girls _ attended. “They packed the upper and lower decks of the left wing of the grandstand and overflowed into the bleachers and pavilion,” the Post-Dispatch reported. Paid attendance was 7,000, putting the total number of spectators at 19,806.

Before the game, Bottomley tossed many baseballs to youngsters in the stands. Then, in a ceremony at home plate, Heydler gave Bottomley $1,000 worth of $5 gold coins in a canvas sack.

During the game, “all available paper was made into schoolroom airplanes and sailed out into the field” by the urchins, the Post-Dispatch noted. Bottomley produced two hits, including a triple, and the Cardinals beat Phillies starter Phil Collins like a drum, winning, 7-2. Boxscore

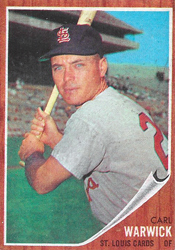

A week before the season ended, Warwick suffered a fractured cheekbone when he was struck by a line drive during pregame drills. He underwent surgery the next day.

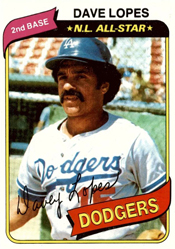

A week before the season ended, Warwick suffered a fractured cheekbone when he was struck by a line drive during pregame drills. He underwent surgery the next day. On Aug. 24, 1974, Lopes had five stolen bases for the Dodgers against the Cardinals. Watching him perform was the National League’s all-time best base stealer, the Cardinals’ Lou Brock.

On Aug. 24, 1974, Lopes had five stolen bases for the Dodgers against the Cardinals. Watching him perform was the National League’s all-time best base stealer, the Cardinals’ Lou Brock. On Aug. 20, 1954, the Cardinals turned six double plays, tying a National League record, and still were beaten, 3-2, at home against the Reds.

On Aug. 20, 1954, the Cardinals turned six double plays, tying a National League record, and still were beaten, 3-2, at home against the Reds. On Aug. 27, 1963, at Candlestick Park in San Francisco, Mays capped a two-month hot streak with his 400th career home run for the Giants.

On Aug. 27, 1963, at Candlestick Park in San Francisco, Mays capped a two-month hot streak with his 400th career home run for the Giants. What Donovan needed more than the luck of the Irish was a dugout full of run producers and premium pitchers.

What Donovan needed more than the luck of the Irish was a dugout full of run producers and premium pitchers.