Batters might have thought Bill Caudill spelled his name with a K, for strikeout, because that’s what happened to many when trying to hit his fastball.

The correct spelling, though, was C, for closer, because that’s what Caudill became in the American League after beginning his career with the Cardinals.

The correct spelling, though, was C, for closer, because that’s what Caudill became in the American League after beginning his career with the Cardinals.

The letter C also fit because this closer was a clubhouse cut-up who caught attention as much for his pranks as for his pitching.

Big-league prospect

As a high school starter in Redondo Beach, Calif., Caudill didn’t lose an Ocean League game in three varsity seasons. Coach Ken Wilson told the Torrance Daily Breeze, “He can really hum it. It used to be where one good catcher mitt would last the whole season, but I’ve had to buy two because he wears them out that quickly _ and I buy top-quality mitts.”

In June 1974, a month before he turned 18, Caudill was chosen by the Cardinals in the eighth round of the amateur draft.

(Of the Cardinals’ top 20 picks in 1974, the only two to reach the majors were shortstop Garry Templeton and Caudill. In the 28th round, St. Louis selected shortstop Paul Molitor, but he opted to attend college.)

Sent to the Cardinals’ rookie club in Sarasota, Fla., Caudill’s teammates included Scott Boras (the future agent), David Boyer (son of Ken Boyer), Lon Kruger (future head basketball coach of the NBA Atlanta Hawks and multiple college teams), Michael Pisarkiewicz (brother of NFL Cardinals quarterback Steve Pisarkiewicz) and Templeton.

Striking out 35 in 30 innings for Sarasota, Caudill was moved up to Class A St. Petersburg in 1975 and excelled there as a starter (14-8, including five shutouts). After Caudill, 19, pitched a one-hit shutout against the Tampa Tarpons, a Reds farm club, in the opening game of the Florida State League championship series, Cardinals director of player personnel Bob Kennedy told the St. Petersburg Times, “You looked at a big-league prospect tonight.”

A right-hander, Caudill went to Class AA Arkansas in 1976, struck out 140 in 140 innings, and was placed on the Cardinals’ 40-man winter roster.

Excited to be here

At his first big-league spring training camp in 1977, Caudill, 20, entered the Cardinals’ clubhouse and hardly could believe his eyes. “I saw Lou Brock and I was awed,” he told the Torrance Daily Breeze.

When Caudill’s hometown team, the Dodgers, arrived for an exhibition game, he stood near the batting cage and marveled at being among hitters he followed as a youth. “These players were just names to me not that long ago,” Caudill said to the Daily Breeze. “(Steve) Garvey, (Ron) Cey, (Davey) Lopes. This is something else. These are guys I watched on television. I paid to see them at Dodger Stadium. I think it’s an honor just to be here on the same field with them.”

Cardinals veterans were “all nice guys,” Caudill told the Torrance newspaper. “They call me Rook … They all came up to introduce themselves and wish me good luck. I dress next to (catcher) Dave Rader. He talks to me. He’s a serious fellow, an established major leaguer, and I listen to him. He helps me, and I appreciate it.”

In his first exhibition game appearance, against the Mets, Caudill’s nervousness showed. He pitched two innings and didn’t allow a hit, but he walked four, hit two batters with pitches and committed a balk.

“Sometimes I sit on the bench sort of in a daze,” Caudill said to the Daily Breeze. “It seems just like yesterday when I was in my high school uniform. I used to listen to these games on the radio.”

The Cardinals planned to have Caudill begin the season at Class AAA, but just before the end of spring training they traded him to the Reds for Joel Youngblood. The Reds initially asked for pitcher Doug Capilla, but the Cardinals countered with Caudill, the Dayton Daily News reported. (Three months later, the Cardinals sent Capilla to the Reds for Rawly Eastwick.)

Windy City welcome

In October 1977, the Reds sought to acquire Cubs pitcher Bill Bonham. Bob Kennedy was now the Cubs general manager. According to the Chicago Tribune, he told the Reds he would make the deal only if they included Caudill, who’d spent the season in the minors. “I raised him as a baby … He’s going to be a good one,” Kennedy told the Tribune.

The Reds accepted the terms, trading Caudill and Woodie Fryman for Bonham.

After more time in the minors, Caudill, 22, reached the big leagues with the Cubs in May 1979. Used as both starter and reliever, he showed promise but experienced growing pains. Caudill struck out 104 in 90 innings. “He’s the hardest thrower in the league,” the Cardinals’ Keith Hernandez, the 1979 National League batting champion, told the St. Louis Post-Dispatch. However, Caudill also gave up 16 home runs, including four in one game against the Dodgers.

With a season record of 0-7, Caudill made his final appearance of 1979 in a relief stint against the Pirates at Pittsburgh. In the 11th inning, with two on and the score tied at 6-6, he struck out slugger Willie Stargell. After the Cubs went ahead with a run in the 13th, Stargell came up with two on and two outs. “I was shaking,” Caudill told the Chicago Tribune. “I had to step off the mound and forget who he was.”

Stargell whiffed again, ending the game and giving Caudill his first win in the majors. “All I threw were fastballs, inside and outside,” Caudill said to The Pittsburgh Press.

Told of Caudill’s comment, Stargell’s teammate, Dave Parker, replied, “That’s all he needs. He’s a good pitcher with good stuff.” Boxscore

No fun

The Cubs made Caudill a reliever in 1980. By September, their bullpen consisted of two future Hall of Famers (Bruce Sutter and Lee Smith), a future American League Most Valuable Player and Cy Young Award winner (Willie Hernandez), the 1980 National League leader in games pitched (Dick Tidrow) and Caudill.

Caudill fit in amid all that talent. In 72 appearances, his ERA was 2.19.

Emboldened by the bullpen depth, the Cubs traded Sutter to the Cardinals, but Caudill regressed in 1981 (5.83 ERA). He said one reason for his poor season was he followed the club’s orders to lose weight. Caudill claimed he dropped at least 20 pounds “but I lost about two feet off my fastball, too,” he told the Los Angeles Times. “My strikeout pitch turned into a single or double pitch.”

Cubs management suggested Caudill’s ineffectiveness was caused by too many late nights on the town. “I found he couldn’t put his body down at night,” Cubs manager Lee Elia told Sports Illustrated. “History had shown here that he couldn’t adapt to day games.”

Caudill said to the magazine, “Show me a Chicago Cub without sacks under his eyes and I’ll show you a Cub who’s only been with the team two weeks.”

Responding to criticism that he was a boisterous presence in the clubhouse, Caudill told Newsday, “The Cubs didn’t really care for all that emotion. It was more like putting on a business suit than a uniform there.”

Elementary, dear Watson

On April 1, 1982, the Cubs sent Caudill to the Yankees, completing a deal for Pat Tabler. Caudill was a Yankee for less than 30 minutes. George Steinbrenner’s club flipped him to the Mariners almost as soon as they acquired him. Regarding his fleeting moments as a Yankee, Caudill told the Los Angeles Times, “Maybe Steinbrenner will send me one pinstripe to put on my mantel.”

Caudill, 25, felt right at home with the Mariners, who made him the closer and encouraged his free spiritedness.

After the Mariners returned from a road trip ruined by a lack of clutch hitting, Caudill reached into his hat collection, pulled out a deerstalker cap and did his best Sherlock Holmes impersonation. “I went up to the bat rack and told everybody I was going to solve The Case of the Missing Hits,” Caudill told the Los Angeles Times. “I took out every bat, looked them over, held them up to my ear and shook them. I threw about four in the trash can. Those were the rotten apples. Now they’re out of the barrel and we’re ready to go.”

Sure enough, the Mariners began producing timely hits. Caudill got dubbed “The Inspector” _ as in Peter Sellers’ Inspector Clouseau _ and was greeted with Henry Mancini’s “The Pink Panther Theme” from the organist whenever he entered a home game. Fans sent him magnifying glasses.

During a rain delay in Detroit, Caudill came onto the field wearing a Beldar the Conehead mask and a jersey of teammate Gaylord Perry with a pillow stuffed underneath. Caudell did an impersonation of the spitball pitcher, “wiping grease from behind his ears and off his eyebrows,” Sports Illustrated noted.

The show ended when Perry tackled Caudill. Though Perry did so good naturedly, “Dick Butkus couldn’t have hit me any harder,” Caudill told the Chicago Tribune.

On another night, Caudill shaved off half his beard. “I told everybody that since we were playing half-assed, I might as well pitch half-bearded,” he told the Sacramento Bee.

Ups and downs

Caudill had 12 wins, 26 saves and 111 strikeouts in 95.2 innings for the 1982 Mariners. The next year, he again earned 26 saves for them. Traded to the Athletics, he posted nine wins and 36 saves in 1984, then got dealt to the Blue Jays for Dave Collins, Alfredo Griffin and cash.

Represented by his former Cardinals minor-league teammate, agent Scott Boras, Caudill got a five-year contract from the Blue Jays. His stay with them, though, was much shorter.

Caudill was removed from the closer role during the 1985 season and replaced by Tom Henke. The next year, shoulder and elbow problems limited Caudill’s effectiveness. Released by the Blue Jays in April 1987, he returned to the Athletics, but broke his right hand when he punched a man Caudill said grabbed his wife in a hotel parking lot, the Associated Press reported. At 31, Caudill was done as a big-league pitcher.

He went to work for Scott Boras and also coached youth baseball. One of the players he instructed, Blake Hawksworth, said Caudill taught him a changeup. Hawksworth used the pitch to reach the majors with the Cardinals in 2009.

In 1958, his first season with the Cardinals, Flood, 20, clouted 10 homers. Those are the most home runs of any Cardinals player 20 or younger, according to researcher Tom Orf.

In 1958, his first season with the Cardinals, Flood, 20, clouted 10 homers. Those are the most home runs of any Cardinals player 20 or younger, according to researcher Tom Orf. On Dec. 15, 1949, the St. Louis Browns obtained Overmire from the Tigers on waivers for $10,000.

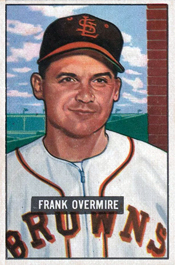

On Dec. 15, 1949, the St. Louis Browns obtained Overmire from the Tigers on waivers for $10,000.

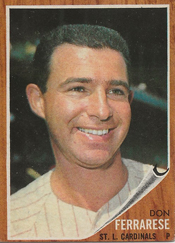

In his first big-league start, Ferrarese struck out 13. In his first win, he held the Yankees hitless for eight innings, then completed the shutout by retiring Mickey Mantle with the potential tying run in scoring position.

In his first big-league start, Ferrarese struck out 13. In his first win, he held the Yankees hitless for eight innings, then completed the shutout by retiring Mickey Mantle with the potential tying run in scoring position. On Nov. 17, 2014, the Cardinals obtained outfielder Jason Heyward and reliever Jordan Walden from the Braves for pitchers Shelby Miller and Tyrell Jenkins. The Cardinals needed a right fielder to replace Oscar Taveras, who died in an auto accident three weeks earlier on Oct. 26.

On Nov. 17, 2014, the Cardinals obtained outfielder Jason Heyward and reliever Jordan Walden from the Braves for pitchers Shelby Miller and Tyrell Jenkins. The Cardinals needed a right fielder to replace Oscar Taveras, who died in an auto accident three weeks earlier on Oct. 26.