Eddie Fisher made sweet music with a pitch that could dance. That’s why the Cardinals wanted his help in their bid for a division title.

On Aug. 29, 1973, the Cardinals purchased the contract of Fisher, 37, from the White Sox. The right-handed knuckleball specialist was in his 15th and final season in the majors.

On Aug. 29, 1973, the Cardinals purchased the contract of Fisher, 37, from the White Sox. The right-handed knuckleball specialist was in his 15th and final season in the majors.

On the day Fisher was acquired, the Cardinals (67-64) led a weak National League East Division. They were two games ahead of the second-place Pirates (63-64) and 6.5 in front of the last-place Mets (60-70).

With Diego Segui, Orlando Pena, Al Hrabosky and Rich Folkers, the Cardinals had a reliable bullpen but wanted the insurance of another experienced reliever for the title run. Fisher fit the bill.

Home on the range

Fisher attended grades one through 12 at Friendship School in Altus, Okla. “There were only 16 in my graduating class, nine boys and seven girls, including Betty Hudgens, whom I later married,” Fisher recalled to The Sporting News.

He excelled in baseball and basketball. His Altus American Legion baseball teammate, Lindy McDaniel, also became a big-league pitcher. As a high school senior, Fisher was a principal player in a major upset. He shut out state powerhouse Capitol Hill, ending its 66-game winning streak in 1954.

“I could throw the knuckler then, but I could win with just a fastball and curve, so I never used it in a game,” Fisher said to The Sporting News.

After graduating, Fisher got a job in Oklahoma City reading gas meters. He also pitched for the company baseball team. Its manager, Roy Deal, was the father of Cardinals pitcher Cot Deal. Roy helped Fisher get an athletic scholarship to the University of Oklahoma.

Fisher didn’t throw the knuckleball in college either. “Eddie didn’t need the knuckler to win in college ball,” head coach Jack Baer explained to The Norman Transcript, “and there are very few catchers, let alone college catchers, who can handle a knuckler.”

As a college junior, Fisher got an offer from the Kansas City Athletics but opted to return to Oklahoma for his senior year. When no offers came after Fisher completed his college career, Roy Deal contacted a minor-league team in Corpus Christi, Texas, and helped him get a roster spot there.

Tuning up

Corpus Christi, a farm club of the Giants in 1958, was managed by a former American League catcher, Ray Murray, who encouraged Fisher to add the knuckler to his assortment of pitches.

A year later, in July 1959, Fisher, 23, was called up to the Giants. For Fisher’s debut, a start against the Pirates, manager Bill Rigney used backup catcher Jim Hegan, 38, who was in his 16th season in the majors. Experienced catching the knuckler, Hegan guided the rookie through the game. Fisher pitched seven innings, limiting the Pirates to one run and three hits, and got the win. Boxscore

A popular singer at the time also was named Eddie Fisher. The singer’s marriages to actresses Debbie Reynolds (their daughter is actress Carrie Fisher), Elizabeth Taylor and Connie Stevens added to his fame. Asked about sharing a name with the crooner, baseball’s Eddie Fisher told The Norman Transcript, “I can’t sing, and what’s more, I don’t like to.”

Teammates nicknamed the pitcher Donald Duck “because of the excellent imitation he does” of the Walt Disney character, The Sporting News noted.

Higher education

After the 1961 season, Fisher was sent by the Giants to the White Sox for pitchers Billy Pierce and Don Larsen. Pierce and Larsen helped the Giants win the 1962 pennant. The White Sox helped Fisher find his niche. The turning point came during the 1964 season when his teammate, knuckleballer Hoyt Wilhelm, persuaded him to use the knuckler as his main pitch.

“We’d be out there together in the bullpen and we’d talk shop,” Fisher told The Sporting News. “He kept hammering away at me to throw the knuckler more. He insisted it was my out pitch and he finally convinced me.”

The bullpen combination of Wilhelm and Fisher confounded American League batters. With the 1964 White Sox, Wilhelm was 12-9 with 27 saves and a 1.99 ERA. Fisher was 6-3 with nine saves and a 3.02 ERA. In 1965, Fisher led American League pitchers in appearances (82) and was 15-7 with 24 saves and a 2.40 ERA. Wilhelm was 7-7 with 21 saves and a 1.81 ERA.

Their knucklers baffled White Sox catcher J.C. Martin as well. Martin had 24 passed balls in 1964 and 33 in 1965.

Fisher was effective against all styles of hitters. Contact hitter Bobby Richardson batted .103 in 29 at-bats against him. Slugger Jim Gentile came up empty _ hitless in 15 career at-bats. “If it’s a good knuckleball, it doesn’t just float. It moves,” Gentile told The Oklahoman. “Swing at it, it might dip, might rise.”

American League batters hit .192 versus Fisher in 1964 and .205 in 1965.

That’s a winner

On June 13, 1966, the White Sox traded Fisher to the Orioles for second baseman Jerry Adair. Fisher joined a bullpen with Stu Miller, Moe Drabowsky and Dick Hall.

Fisher made an immediate impact, earning a save or a win in five of his first seven appearances with the Orioles. He pitched in 44 games for them and was 5-3 with 14 saves and a 2.64 ERA. The Orioles (97-63) won the pennant.

Though Fisher led the league in appearances (67 combined for the White Sox and Orioles) for the second year in a row, he didn’t pitch in the 1966 World Series versus the Dodgers. The Orioles swept, getting shutouts from Jim Palmer, Wally Bunker and Dave McNally. The only Orioles reliever to appear in that World Series was Drabowsky, who pitched 6.2 scoreless innings and struck out 11 in Game 1.

Fisher never got to play for another World Series participant. He was with the Indians in 1968 and the Angels from 1969-72 before returning to the White Sox.

Final season

At spring training in 1973, Fisher, 36, had a 1.33 ERA in 27 innings pitched in exhibition games. White Sox manager Chuck Tanner and pitching coach Johnny Sain decided to open the season with Fisher as their No. 3 starter behind another knuckleballer, Wilbur Wood, and Stan Bahnsen.

Fisher won four of his first five decisions, but the good times didn’t last. He slumped in June (10.67 ERA in five starts) and was moved back to the bullpen. In 10 relief appearances covering 35.1 innings, he had a 3.57 ERA, prompting the Cardinals to acquire him. Barney Schultz, Cardinals pitching coach in 1973, helped St. Louis win a World Series title in 1964 as a knuckleball reliever who joined the club in August.

Cardinals manager Red Schoendienst put Fisher to work, pitching him in three consecutive games. In his second appearance, on Sept. 2, 1973, Fisher got the win with a scoreless inning of relief against the Mets. The triumph gave the Cardinals (69-67) sole possession of first place in the division, a game ahead of the Pirates (66-66), and pushed the Mets (63-72) nine games below .500. Boxscore

The next day, the Cardinals played a doubleheader against the Pirates. In the opener, with the score tied at 4-4, Fisher entered in the bottom of the 13th inning. The first batter he faced, Richie Hebner, clobbered a knuckleball to deep right.

“I definitely thought it was gone,” Cardinals catcher Ted Simmons told The Pittsburgh Press. “I was ready to walk off the field.”

Instead, the ball hit the wall and caromed past right fielder Jose Cruz. Center fielder Luis Melendez didn’t back up Cruz as he should. The ball bounced along the artificial surface of the outfield as Hebner steamed around the bases.

Melendez said to The Pittsburgh Press, “I’ve got to be there (backing up the play). If I get there when I was supposed to, it only would have been a double.”

When Melendez finally got to the ball, he reached for it and didn’t come up with it. He reached a second time and again couldn’t grab it. Pirates third-base coach Bill Mazeroski told The Pittsburgh Press that he intended to hold Hebner at third, but when Melendez twice failed to retrieve the ball, “I sent him in. If he picks it up the first or second time, I don’t send him in.”

Hebner scooted to the plate with a walkoff inside-the-park home run, and Fisher was the losing pitcher. Boxscore

Two weeks later, on Sept. 17, Fisher got a win, pitching two scoreless innings and driving in a run with a single against the Expos’ Mike Marshall. Boxscore

By then, though, the Cardinals (74-76) were sliding. The Mets won seven in a row from Sept. 18 to Sept. 25 and finished as the only team in the division with a winning record (82-79).

(The 1973 Cardinals ended 81-81, sixth overall in the National League, a finish that today would have them popping champagne corks and selling postseason merchandise as lame playoff qualifiers.)

Fisher was released by the Cardinals after the season, ending his playing days. He was 2-1 with a 1.29 ERA for them. For his career in the majors, Fisher was 85-70 with 82 saves.

Duke Carmel certainly fit the part. He was named after Duke Snider, had the mannerisms of Ted Williams and could hit with the power of Mickey Mantle.

Duke Carmel certainly fit the part. He was named after Duke Snider, had the mannerisms of Ted Williams and could hit with the power of Mickey Mantle. Having worn out his welcome in New York, Allen felt instantly unwelcomed in St. Louis when the Cardinals

Having worn out his welcome in New York, Allen felt instantly unwelcomed in St. Louis when the Cardinals  Pena worked his wizardry for the Cardinals after they acquired him from the Orioles for cash on June 15, 1973.

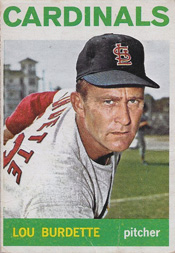

Pena worked his wizardry for the Cardinals after they acquired him from the Orioles for cash on June 15, 1973. On June 15, 1963, the Cardinals obtained Burdette, 36, from the Braves for catcher

On June 15, 1963, the Cardinals obtained Burdette, 36, from the Braves for catcher  He made a good run at it, playing in the farm systems of baseball’s Milwaukee Braves and hockey’s Detroit Red Wings.

He made a good run at it, playing in the farm systems of baseball’s Milwaukee Braves and hockey’s Detroit Red Wings.