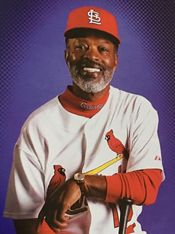

As a pinch-hitter in 1985, Hal McRae helped the Royals emerge from the brink of elimination against the Cardinals and advance to their first World Series championship. As a hitting coach two decades later, McRae helped the Cardinals become World Series champions for the first time in 24 years.

McRae spent more than 40 years in the big leagues _ 19 as a player, 15 as a coach, six as a manager and two in the front office. His last five seasons in the majors were as hitting coach of the Cardinals from 2005 to 2009.

McRae spent more than 40 years in the big leagues _ 19 as a player, 15 as a coach, six as a manager and two in the front office. His last five seasons in the majors were as hitting coach of the Cardinals from 2005 to 2009.

During McRae’s St. Louis stint, the Cardinals won a World Series title in 2006, their first since 1982.

Segregated South

Harold McRae was from Avon Park, Fla., 85 miles south of Orlando. From 1927 to 1929, Avon Park was spring training home of the Cardinals.

As a youth in the 1950s, McRae developed into a right-handed hitter playing stickball on a makeshift diamond at the corner of Delaney and Castle streets in Avon Park. “A lot of skills I exhibited in the big leagues began right (there),” McRae recalled to the Tampa Tribune. “I remember a certain Mrs. Austin who lived on that corner. We knew that if we hit a ball into her yard, which was left field, she wouldn’t give it back. So that’s how I first learned to hit to right field.”

(In 1991, Castle Street was renamed Hal McRae Boulevard.)

McRae attended segregated E.O. Douglas High School in Sebring, Fla. Named for banker Eugene Oren Douglas, it was the only high school in the county available to blacks. (The school remained open until 1970, when integration finally occurred in Highlands County.)

After graduating in 1963, McRae attended Florida A&M in Tallahassee. Two years later, the Reds signed him. “I really enjoyed sliding headfirst, taking out the middle infielders, running into the catcher,” McRae told the Tampa Tribune. “I credit that outlook to my baseball coach (Costa Kittles) at Florida A&M. He was really a football coach. I was never afraid of contact.”

A few months after turning pro, McRae married his wife, Johncyna, in April 1966. Forty years later, in 2006, she was presented with an unsung hero award from the Florida Department of Health for “working tirelessly to end disparities in health care for racial and ethnic minorities.”

The award was presented with accolades from Florida Gov. Jeb Bush. According to the Bradenton Herald, Dr. Gladys Branic, director of the Manatee County Health Department, praised Johncyna “for her mentoring of migrant workers, her volunteer work for troubled teens, and the many scholarships and nurturing programs she helped develop for black girls.”

Slotted for second

In his first three seasons in the Reds’ system (1966-68), McRae was a second baseman. His minor-league manager in 1967 was former second baseman Don Zimmer. At the Florida Instructional League that fall, McRae’s instructor was former second baseman Sparky Anderson. Reds manager Dave Bristol told The Cincinnati Post, “Everyone, including scouts on the other clubs, tells me McRae is going to be Cincinnati’s next second baseman.”

McRae was called up to the Reds during the 1968 season and started 16 games at second base. Then in the winter, playing in Puerto Rico, he fractured his right leg in four places trying to knock the ball loose from a catcher on a play at the plate. That put an end to his ability to move nimbly as a second baseman.

After sitting out most of the 1969 season, McRae was shifted to the outfield and was with the Reds from 1970-72. In two World Series, he hit .455 against the Orioles in 1970 and .444 versus the Athletics in 1972. Video

(McRae also played in two World Series with the Royals. In 17 World Series games, he hit .400.)

Rough stuff

Traded to the Royals in November 1972, McRae benefitted from the American League’s adoption of the designated hitter in 1973. He told the Tampa Tribune, “Some people considered it being half a ballplayer … It just so happened that my best role was as the DH.”

Working well with hitting coaches such as Charley Lau and Rocky Colavito, McRae hit better than .300 seven times in 15 years with the Royals.

In 1976, when McRae hit .332, his teammate, George Brett, won the American League batting title at .333. In his final at-bat, Brett got an inside-the-park home run when Twins outfielder Steve Brye misjudged the ball. McRae suggested Brye intentionally let the ball drop.

Because of his aggressiveness, McRae was not a popular opponent. According to the Baseball Hall of Fame, while managing the White Sox, Tony La Russa said of McRae, “When you play against him, you detest him, but you would love to have him on your side.”

Mariners pitcher Glenn Abbott told Sports Illustrated, “I feel McRae has played dirty, but he plays to win, and that’s what it’s all about.”

Attempting to thwart a double play during a 1977 playoff game, McRae barreled into Yankees second baseman Willie Randolph with a rolling body block. The Yankees cried foul, but McRae said to United Press International, “I wasn’t trying to hurt Randolph … There was nothing dirty about it … We’re not supposed to be buddy-buddy out there.” Video

Teammates respected McRae. George Brett said to Sports Illustrated, “I look up to him. He learned the game from Pete Rose, and I learned it from him.” Whitey Herzog, McRae’s manager from 1975-79, told the Kansas City Star, “He’s the best designated hitter in baseball. He gives you everything he has on every play.”

Patience pays

The 1985 World Series between the Royals and Cardinals was played without designated hitters, but McRae still was involved in the drama.

With the Cardinals ahead, 1-0, in the ninth inning of Game 6 and on the verge of clinching the championship, the Royals got a break when umpire Don Denkinger ruled Jorge Orta safe at first, though TV replays clearly showed he was out.

As the inning unfolded, the Royals had runners on first and second, one out, when McRae batted for Buddy Biancalana. The Cardinals’ right-handed rookie closer, Todd Worrell, hoped to get McRae to ground into a game-ending double play.

According to the Kansas City Star, McRae said he reminded himself as he approached the plate to be patient and swing only if the pitch was a strike.

With the count 1-and-0, Worrell threw a slider that eluded catcher Darrell Porter for a passed ball, enabling the runners to move up to second and third. That changed the strategy. Behind in the count 2-and-0, Cardinals manager Whitey Herzog ordered Worrell to walk McRae intentionally, loading the bases and setting up a potential force-out at any base.

A left-handed batter, ex-Cardinal Dane Iorg, thwarted the plan with a two-run single. The Royals clinched the title the next night in Game 7. Boxscore

Good teacher

McRae batted .290 and totaled 2,091 hits in a big-league playing career that ended in 1987.

He managed the Royals (1991-94) and Rays (2001-02). A son, Brian, became a big-league outfielder and played for him on the Royals.

McRae coached for the Royals (1987), Expos (1990-91), Reds (1995-96), Phillies (1997-2000) and Rays (2001). As hitting coach, he was credited with helping develop Reggie Sanders with the Reds and Scott Rolen with the Phillies.

“Hitting instruction is probably my first love,” McRae told Todd Jones of The Cincinnati Post. “I enjoy the interaction with the players. As a manager, you look for results. As a hitting instructor, you look for improvement.”

After McRae helped Deion Sanders snap a slump, Reds veteran Lenny Harris told The Post, “Deion said to us, ‘It’s time to start listening to Hal McRae. He understands us.’ “

In a report on McRae’s hitting philosophy, Jim Salisbury of the Philadelphia Inquirer noted, “The plate is 17 inches wide. McRae teaches his hitters to concede the inner and outer two inches to the pitcher. That leaves 13 inches for the hitter.”

After being replaced as Rays manager by Lou Piniella, McRae moved into the role of assistant to Rays general manager Chuck LaMar, but there were “few requests for his input,” according to the St. Petersburg Times.

“I felt miserable half the time,” McRae told the newspaper.

Back in uniform

With Mitchell Page as hitting coach, the 2004 Cardinals won the National League pennant and led the league in hits and runs scored, but he was fired for reasons related to alcoholism. Page said to Joe Strauss of the St. Louis Post-Dispatch, “I have an alcohol problem and I’m going to get treatment for it.”

The Cardinals offered the job to McRae, 59, and he welcomed the chance to coach again. Recalling his start as a big-league manager with the White Sox in 1979, Cardinals manager Tony La Russa told the Bradenton Herald, “Winning was defined by George Brett and Hal McRae. In the West Division, Kansas City was the team to beat, and those were the two guys who showed how it was done. I always said I’d like to be a teammate of Hal McRae.”

After his hiring, McRae watched video and learned the habits of Cardinals batters. At 2005 spring training, he spent each day talking with the players and tailored his philosophies to their needs. As Roger Mooney of the Bradenton Herald noted, “McRae coaches like he played. He’s prepared, works hard and gets results.”

The 2005 Cardinals were loaded with big hitters such as Jim Edmonds, Albert Pujols, Scott Rolen, Reggie Sanders and Larry Walker. “With a veteran club, you’re talking about the (opposing) pitcher,” McRae said to the Herald. “We’re more concerned with the pitcher than ourselves.”

Helping hand

The 2006 Cardinals were a deeply flawed team that became World Series champions. Part of their success stemmed from the performance of rookie Chris Duncan, who slugged 22 home runs in 280 at-bats during the season.

“Hal McRae has been the biggest help because he’s working with me day in, day out,” Duncan told the Post-Dispatch. “He’s helped me the most to get through different phases and whatever is going on with me.”

In assessing McRae’s contributions to the 2006 Cardinals, Tony La Russa said to the St. Petersburg Times, “He’s a very smart man. He understands what hitting is about … and he understands winning.”

When Albert Pujols slumped early in the 2007 season, McRae gave him a tutorial _ “He needs to use his hands more,” the coach told the Post-Dispatch _ and used a video to convince Pujols that by being impatient, or jumpy, at the plate he was opening his hips too early in his swing. “He showed me, and I saw the difference,” Pujols said to reporter Joe Strauss.

In 2008, the Cardinals led the league in hits and batting average (.281, well above the league norm of .260), and got big production from a journeyman (Ryan Ludwick, 37 home runs, 113 RBI) and a former pitcher (Rick Ankiel, 25 homers).

Though division champions in 2009, the Cardinals were swept by the Dodgers in the playoffs, totaling six runs in three games. McRae, 64, was fired.

“You’re always disappointed when you get laid off,” McRae told the Post-Dispatch, “but I’m not disappointed in my work.”

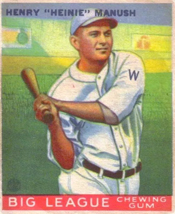

Entering the ninth inning, Goslin was tied with Heinie Manush of the St. Louis Browns for the league’s top batting average. If Goslin got a hit, he’d win the batting crown. If he made an out, Manush would gain the title.

Entering the ninth inning, Goslin was tied with Heinie Manush of the St. Louis Browns for the league’s top batting average. If Goslin got a hit, he’d win the batting crown. If he made an out, Manush would gain the title. Manush reached the majors with the 1923 Tigers. The nickname Heinie was slang for Heinrich, a German form of the name Henry. Manush became a protege of his Tigers manager Ty Cobb, who taught him to shorten his stroke and try for hits instead of homers.

Manush reached the majors with the 1923 Tigers. The nickname Heinie was slang for Heinrich, a German form of the name Henry. Manush became a protege of his Tigers manager Ty Cobb, who taught him to shorten his stroke and try for hits instead of homers. Standing 6-foot-6 and weighing 220 to 280 pounds, Veale made some of the National League’s best hitters look inept. Lou Brock (.194 in 93 at-bats), Willie McCovey (.188 in 48 at-bats) and Ernie Banks (.108 in 83 at-bats) had career batting averages below .200 against Veale.

Standing 6-foot-6 and weighing 220 to 280 pounds, Veale made some of the National League’s best hitters look inept. Lou Brock (.194 in 93 at-bats), Willie McCovey (.188 in 48 at-bats) and Ernie Banks (.108 in 83 at-bats) had career batting averages below .200 against Veale. A few days before the June 2000 baseball draft, the Reds brought Molina, 17, from his home in Puerto Rico to work out with other potential picks at Cincinnati’s Riverfront Stadium.

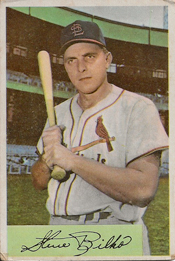

A few days before the June 2000 baseball draft, the Reds brought Molina, 17, from his home in Puerto Rico to work out with other potential picks at Cincinnati’s Riverfront Stadium. From the moment the Cardinals signed him, in 1945, Bilko intrigued with his power. He was big _ 6-foot-1 and, as the St. Louis Star-Times noted, “230 pounds of man” _ with thick legs and trunk.

From the moment the Cardinals signed him, in 1945, Bilko intrigued with his power. He was big _ 6-foot-1 and, as the St. Louis Star-Times noted, “230 pounds of man” _ with thick legs and trunk. A utilityman whose best position was second base, Sutherland played 13 seasons in the majors with the Phillies (1966-68), Expos (1969-71), Astros (1972-73), Tigers (1974-76) and Padres (1977) before finishing with the 1978 Cardinals.

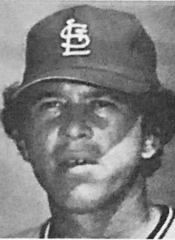

A utilityman whose best position was second base, Sutherland played 13 seasons in the majors with the Phillies (1966-68), Expos (1969-71), Astros (1972-73), Tigers (1974-76) and Padres (1977) before finishing with the 1978 Cardinals.