When the Cardinals offered Rico Carty the chance to begin his professional baseball career with them, the right-handed power hitter from the Dominican Republic was receptive. Then again, Carty was agreeable to signing with any club.

Away from home for the first time, Carty, 19, played in the Pan-American Games at Chicago in 1959. Impressed by his hitting, several big-league clubs sought to sign him.

Away from home for the first time, Carty, 19, played in the Pan-American Games at Chicago in 1959. Impressed by his hitting, several big-league clubs sought to sign him.

“The Cardinals made the best offer, $2,000, and I wanted to go with them,” Carty told the St. Louis Post-Dispatch.

Unschooled in English, Carty signed with the Cardinals and also with at least three other teams _ Braves, Giants and Pirates. “I didn’t know you couldn’t sign with more than one club,” Carty told the Associated Press.

Carty also was under contract to Estrellas, a professional team in the Dominican Republic. When the Braves made a deal with Estrellas to acquire the rights to Carty, he became a member of the Milwaukee organization and all other contracts were voided, the Post-Dispatch reported.

A National League batting champion (.366 in 1970), Carty played for 15 seasons with the Braves and five other clubs in a career marked by health and injury woes, conflict and controversies.

Finding his way

Carty had 15 brothers and sisters. His father worked in a sugar mill and his mother was a midwife. As a teen, Carty became an amateur boxer, winning 17 of 18 bouts, but quit at the insistence of his mother, according to the Post-Dispatch.

His slugging on the diamond got him to the pros, but his fielding held him back. When Carty entered the Braves’ farm system in 1960, they tried him at catcher. As Carty recalled to the Atlanta Journal, “I was really brutal catching.”

With the Austin (Texas) Senators in 1963, Carty was moved to the outfield. He produced 100 RBI and was hailed “the best hitting prospect in the organization,” according to The Sporting News.

Called up to the Braves in September 1963, Carty, 24, made his major-league debut in a pinch-hitting stint at St. Louis and struck out against Ray Sadecki. Boxscore

Big-league bat

Batting .408 at spring training in 1964, Carty made the Braves’ Opening Day roster and continued his torrid hitting.

On May 23, 1964, at Milwaukee, Carty clouted two home runs for five RBI against the Cardinals’ Roger Craig. Boxscore

Carty’s hitting, combined with his adventures in the outfield, made him the darling of the bleacher fans at Milwaukee’s County Stadium. “They cheer every move he makes,” The Sporting News noted. “He is a thrill a minute fielder, the type who starts the wrong way on a ball and winds up making a circus catch.”

For the season, Carty hit .330. Against the Cardinals, who became 1964 World Series champions, the rookie batted .343 in 18 games.

Applying the hammer

The Braves moved to Atlanta after the 1965 season and Carty became a fan favorite there, too.

“Carty can most definitely charm the fans,” Frank Hyland of the Atlanta Journal observed. “They love him and he plays them like a drum. There is perhaps no athlete in any sport who makes himself as available as Carty.”

Rod Hudspeth of the Atlanta Journal added, “Carty has a lot of ham and a little con artist in him. He knows exactly when to turn and flash the big smile to a fan wanting a snapshot, the precise time to sign autographs and milk the most mileage from them, and the opportune moment to toss a baseball into the stands and get the big crowd reaction.”

Inside the clubhouse, it was a different story. “He was not well-liked by many teammates,” the Journal reported. Columnist Furman Bisher noted, “Teammates give him wide berth, even fellow Dominicans Felipe Alou and Sandy Alomar.”

In his autobiography “Alou: My Baseball Journey,” Felipe Alou said, “About the only guy I ever saw Hank (Aaron) have a problem with was Rico Carty … Rico was easy to have a problem with. He was defiant, belligerent, constantly challenging … Rico was a brawny guy who liked to intimidate people.”

On a Braves charter flight from Houston to Los Angeles in 1967, Carty got into an argument with Aaron and it boiled over into a fight.

In his autobiography “I Had a Hammer,” Aaron said, “Carty was playing cards two rows behind me when I heard him call me a ‘black slick.’ I stood up and asked him what he said, and he repeated it … A second later, we were swinging at each other … My fist went right by his head and put a hole in the luggage rack of the plane. Our teammates finally broke it up. I think there were three guys holding me.”

Aaron and Carty each told the Atlanta Constitution he was sorry the fight happened, but Aaron added, “He called me a name that I couldn’t take, and I would have fought anybody for that. It was a matter of principle and pride … If I’m called that name again, I’ll fight again.”

Carrying on

At spring training in 1968, Carty was diagnosed with tuberculosis. While undergoing six months of treatment in a sanatorium at Lantana, Fla., Carty received a letter from Cardinals manager Red Schoendienst, who was stricken with tuberculosis shortly after he played for the Braves in the 1958 World Series. “He said I was lucky that I would not have to be cut, like him,” Carty told Ira Berkow of Newspaper Enterprise Association. (Schoendienst underwent surgery to remove part of an infected lung.)

Back with the Braves in 1969, Carty suffered three shoulder separations but hit .342, helping Atlanta win a division title. Columnist Jesse Outlar noted, “That seemed inconceivable. You simply don’t spend an entire year in a hospital, then belt major league pitching at that clip with bum or sound shoulders.”

Carty, 30, reached his peak with the 1970 Braves. He batted .423 for April, .448 for May and put together a 31-game hitting streak. Though left off the All-Star Game ballot, a flood of write-in votes from the fans made him a National League starting outfielder along with Hank Aaron and Willie Mays.

A month later, Carty got into a clubhouse scuffle with teammate Ron Reed.

The season ended with Carty as the league leader in hitting (.366) and on-base percentage (.454). He produced the highest batting average to lead the National League since Stan Musial hit .376 for the Cardinals in 1948.

Tough to take

Good times were followed by the bad. In December 1970, Carty suffered a triple fracture of his left knee, plus torn cartilage, when he collided with Matty Alou while chasing a fly ball during a game in the Dominican Republic. The severity of the injury prevented Carty from playing in 1971.

More trouble awaited.

In August 1971, while Carty and his brother-in-law, Carlos Ramirez, were in a car at a stoplight in Atlanta, two off-duty policemen pulled up alongside and accused them of being “cop-killing niggers,” the Atlanta Journal reported.

Carty noticed a uniformed officer inside a police car nearby and drove up to report what had happened. The off-duty cops followed and there was an altercation. Carty said the three white policemen beat him and his brother-in-law, using a billy club and the butt of a revolver. Carty and his relative were handcuffed and arrested on charges of assault and creating turmoil.

Atlanta mayor Sam Massell said the police actions appeared to be “blatant brutality,” United Press International reported.

Upon review, the three cops were fired by Atlanta police chief Herbert Jenkins. According to the Atlanta Constitution, Jenkins called it “the worst case of misconduct of a police officer I’ve ever seen.”

In dismissing all charges against Carty and his brother-in-law, Municipal Court Judge Robert M. Sparks Jr. said the defendants were “shamefully handled.”

Soon after, in an unrelated incident, Carty’s barbecue restaurant in Atlanta was destroyed in a fire.

Slow motion

Carty’s attempt to come back from the shattered knee and other ailments (he was hospitalized for pleurisy in 1971) was a struggle. At 1972 spring training, he said to United Press International, “When I came back after being sick with tuberculosis, it was just a matter of resting and building up my strength. Now there is pain to overcome. It does not hurt when I bat, but when I run it hurts.”

Braves manager Lum Harris told the wire service, “Rico never was a speedster, but I’ve never seen him as slow as he is now.”

Carty played in 86 games for the 1972 Braves, hit .277 and was traded to the Rangers for pitcher Jim “Pink” Panther.

The Rangers figured Carty to be an ideal designated hitter, but manager Whitey Herzog wasn’t impressed with what he saw. In the book “Seasons in Hell,” Herzog said to author Mike Shropshire, “When Rico runs from home plate to first, you could time him with a sundial.” Herzog also said he thought Carty was “crazier than a peach orchard sow.”

After a game against the Orioles, Carty told Shropshire he intentionally fouled off a pitch he thought was ball four because he didn’t want to spoil Jim Palmer’s bid for a perfect game. When Shropshire informed Herzog of this, the manager rolled his eyes and replied, “What a bunch of crap.”

According to the Fort Worth Star-Telegram, Herzog and Carty almost got into a dugout fistfight in June after Carty cussed Herzog for not backing him in a dispute with an umpire over a called strike. Soon after, Carty was sent packing. He finished out the season with the Cubs and Athletics.

Unwanted in the majors, Carty, 34, went to the Mexican League in 1974.

Another stab

Once again, Carty showed it was unwise to count him out. He hit .354 in the Mexican League. That impressed the Cleveland Indians, who brought him back to the majors in August 1974.

In four seasons with Cleveland, Carty batted .303, but he and manager Frank Robinson clashed. Robinson described his relationship with Carty as “a cold war,” the Associated Press reported.

Carty and Robinson soon were gone from Cleveland. Carty had one more big season, 1978, when he combined for 31 home runs and 99 RBI with the Blue Jays and Athletics.

During a road trip with the Blue Jays in 1979, a toothpick pierced Carty’s finger when he reached into a travel bag. Carty removed part of the toothpick, but the tip remained lodged under the skin.

“The thing keeps me from gripping the bat right, but they tell me it will work its way out eventually,” Carty told the Toronto Star.

The finger got infected and Carty “had to squeeze pus from his hand before hitting,” the Star reported.

Though the sliver finally was removed, his batting average sank like a martini olive untethered from its cocktail stick. He ended the season, his last, at .256.

That cost Carty a .300 career batting mark. He settled instead for .299.

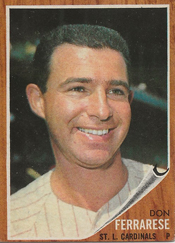

In his first big-league start, Ferrarese struck out 13. In his first win, he held the Yankees hitless for eight innings, then completed the shutout by retiring Mickey Mantle with the potential tying run in scoring position.

In his first big-league start, Ferrarese struck out 13. In his first win, he held the Yankees hitless for eight innings, then completed the shutout by retiring Mickey Mantle with the potential tying run in scoring position. In 1931, Street piloted the St. Louis Cardinals to their second consecutive National League pennant and a World Series title. Seven years later, as manager of the 1938 St. Louis Browns, his American League team had a 53-90 record before he was fired with 10 games left in the season.

In 1931, Street piloted the St. Louis Cardinals to their second consecutive National League pennant and a World Series title. Seven years later, as manager of the 1938 St. Louis Browns, his American League team had a 53-90 record before he was fired with 10 games left in the season. On Nov. 17, 2014, the Cardinals obtained outfielder Jason Heyward and reliever Jordan Walden from the Braves for pitchers Shelby Miller and Tyrell Jenkins. The Cardinals needed a right fielder to replace Oscar Taveras, who died in an auto accident three weeks earlier on Oct. 26.

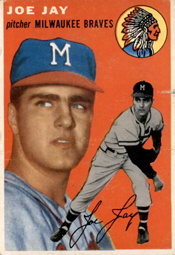

On Nov. 17, 2014, the Cardinals obtained outfielder Jason Heyward and reliever Jordan Walden from the Braves for pitchers Shelby Miller and Tyrell Jenkins. The Cardinals needed a right fielder to replace Oscar Taveras, who died in an auto accident three weeks earlier on Oct. 26. A right-hander, Jay became the first former Little League player to reach the majors when he joined the Braves out of high school at 17 in 1953.

A right-hander, Jay became the first former Little League player to reach the majors when he joined the Braves out of high school at 17 in 1953.