Frank Ryan, a quarterback who excelled at advanced mathematics and physics, sought the formula for beating the St. Louis Cardinals defense.

In his 13 seasons (1958-70) in the NFL with the Los Angeles Rams, Cleveland Browns and Washington Redskins, Ryan had more ups than downs versus the Cardinals but it wasn’t easy. He started 12 games against them and was intercepted 14 times. No other team picked off more of his passes.

In his 13 seasons (1958-70) in the NFL with the Los Angeles Rams, Cleveland Browns and Washington Redskins, Ryan had more ups than downs versus the Cardinals but it wasn’t easy. He started 12 games against them and was intercepted 14 times. No other team picked off more of his passes.

In 1965, the year after he led the Browns to a NFL championship, Ryan was intercepted seven times in two starts versus the Cardinals. The next year, he made the right calculations and had one of the most productive passing games of his career against them.

During a time when the NFL featured Bart Starr, Fran Tarkenton and Johnny Unitas, Ryan twice led the league in touchdown passes _ 25 in 14 games in 1964 and 29 in 14 games in 1966.

Rocket man

As a youngster in Fort Worth, Texas, Ryan took an interest in math and science. By age 6, “he spent a lot of his time drawing sideview cutaway sketches of rockets and figuring out how fast a space missile would have to go to break out of the earth’s gravitational pull,” according to Sports Illustrated.

After high school, he enrolled at Rice, majoring in physics and playing quarterback. As a junior in 1956, Ryan split time with another quality quarterback, King Hill.

Ryan started Rice’s season opener his senior year but got injured. Hill replaced him and remained the starter, breaking the school record for total offense and guiding Rice to a berth in the Cotton Bowl.

In the 1958 NFL draft, the Chicago Cardinals, with the first two picks in the first round, took Hill and Texas A&M running back John David Crow. Ryan was chosen in the fifth round by the Rams. Upon earning his bachelor’s degree in physics, Ryan planned to pursue a master’s in advanced mathematics at Rice. He agreed to sign with the Rams after it was arranged for him to take classes at UCLA during the football season.

Asked about drafting a quarterback who was the backup to King Hill, Rams head coach Sid Gillman replied to the Chicago Tribune, “Ryan is the better bet. He would have been drafted sooner, only no one believes he’ll try pro football.”

California dreaming

While serving as backup to Rams starting quarterback Bill Wade, Ryan took two courses in math logic at UCLA.

Asked whether trying to master the Rams’ playbook was as difficult as graduate studies, Ryan said to the Los Angeles Times, “Both are largely a matter of memory, but with math, you can apply what you’ve memorized to attacking a problem with original thinking. Whereas I doubt if Coach Gillman would appreciate too much original thinking on my part where ‘Split Right, Take 18, Waggle Left, Pass X Comeback” is concerned.

“Let’s put it this way: The difference is that in football, you think quicker, but not as deeply. Science allows you more leisure to think, but you have to think deeper.”

When the Rams went on road trips, Ryan’s wife, Joan, sat in for him at class and took notes. “Give her a week, and she’ll understand it as well as I do,” Ryan told the Times.

(Joan Ryan graduated from Rice with a degree in English literature. When her husband joined the Browns, she became a sports columnist for the Cleveland Plain Dealer. She later was a sports columnist for the Washington Star and Washington Post. She was one of two sports columnists named Joan Ryan. The other worked for San Francisco newspapers and was no relation.)

Ryan backed up Bill Wade in 1958 and 1959, and was in the same role in 1960 when Bob Waterfield replaced Gillman as Rams head coach.

On Sept. 23, 1960, the Cardinals, who had moved from Chicago to St. Louis, opened the season against the Rams. King Hill was the Cardinals’ starting quarterback. He struggled and was replaced at halftime by John Roach, who threw four touchdown passes and carried the Cardinals to a 43-21 victory. Ryan played in the second half for the Rams and threw a 54-yard touchdown pass to rookie Carroll Dale. Game stats

Midway through the 1960 season, the Rams went with Ryan as the starter. On Oct. 30, he threw three touchdown passes, including one to himself, in a 48-35 triumph over the Detroit Lions, snapping the Rams’ streak of 13 consecutive winless games.

Ryan’s touchdown reception happened this way: He threw a short pass to halfback Jon Arnett, who got blanketed by defenders. Arnett turned, saw Ryan and lateraled the ball to him. “I was the most surprised guy on the field,” Ryan said to the Fort Worth Star-Telegram. “I ran about 25 yards. I barely beat Night Train Lane to the end zone.” The play went into the books as a 37-yard touchdown pass from Ryan to Ryan.

Head coach Bob Waterfield said to the Los Angeles Times, “That was a new one on me. I asked Ryan later: Where did we get that play?” Game stats

The next year, much to Ryan’s chagrin, Zeke Bratkowski became the Rams’ starting quarterback. Ryan had one highlight. On Oct. 1, 1961, substituting for an injured Bratkowski, he connected with Ollie Matson on a 96-yard touchdown pass against the Pittsburgh Steelers. Game stats

After making quarterback Roman Gabriel their top pick in the 1962 draft, the Rams saw no need for Ryan. On July 12, 1962, Ryan’s 26th birthday, he and running back Tom Wilson were traded to the Browns for defensive tackle Larry Stephens and two 1963 draft choices.

Dr. Ryan

Jim Ninowski opened the 1962 season as the Browns’ starting quarterback but broke his collarbone in the eighth game and was replaced by Ryan, who held on to the job.

In 1964, the Browns played the Baltimore Colts for the NFL championship. Johnny Unitas was the Colts’ quarterback, but Ryan “completely stole the show,” The Sporting News noted. He threw three touchdown passes to flanker Gary Collins and the Browns won, 27-0. Game stats

Six months later, Ryan got his doctorate in advanced mathematics from Rice. His doctoral dissertation was titled: “A Characterization of the Set of Asymptotic Values of a Function Holomorphic in the Unit Disc.”

“The world outside has no conception of what higher mathematics is about,” Ryan said to Sports Illustrated. “The heart and soul of modern mathematics is very abstract symbolism. People think mathematicians are concerned with numbers, and they’re not at all. Advanced mathematics is unrelated in a casual way to anything else, including football.”

Ryan became a professor of higher mathematics at Case Western Reserve University in Cleveland while playing for the Browns. He taught fulltime in the spring semester and twice a week during football season.

Big Red menace

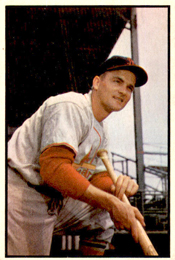

The defending champion Browns began the 1965 season with a win at Washington and then prepared for their Sept. 26 home opener against the Cardinals. Ryan appeared on the cover of Sports Illustrated that week.

The Cardinals were unimpressed. Ryan “had what must have been his saddest day in the NFL,” according to the Mansfield News-Journal. He was intercepted four times, injured a foot and “left the game with a broken heart” late in the first half, the Akron Beacon Journal noted. The Cardinals won, 49-13.

“The (foot) injury had a good deal to do with Ryan’s performance,” the Akron newspaper reported. “He was unable to set himself properly and throw _ and the results were passes resembling winged ducks.”

Jim Ninowski, who replaced Ryan in the game, was intercepted twice, giving the Cardinals a total of six. Jimmy Burson and Jerry Stovall each had two. Pat Fischer and Larry Wilson had one apiece. Wilson picked of another but it was nullified by a penalty. Game stats

In the rematch at St. Louis three months later, Wilson intercepted three Ryan passes and returned the first 96 yards for a touchdown. Browns running back Jim Brown (ejected for fighting with Cardinals defensive lineman Joe Robb) and flanker Gary Collins (rib injury) departed in the first half, but Ryan overcame the challenges and led the Browns to a 27-24 triumph. Game stats

The next year, with better pass protection, Ryan improved versus the Cardinals. Intercepted seven times by them in 1965, he was picked off just once in two games against the 1966 Cardinals. In the Dec. 17 season finale, a 38-10 Browns victory, Ryan threw for a career-high 367 yards, including four touchdown passes, and was not intercepted. Game stats

Good, bad and ugly

Bill Nelsen replaced Ryan as the the Browns’ starting quarterback in 1968. Ryan spent his final two NFL seasons _ 1969 (when Vince Lombardi was head coach) and 1970 _ with the Redskins as backup to Sonny Jurgensen.

Afterward, Ryan was director of information and computer systems for the United States House of Representatives from 1971-77. In 1977, Yale named him its athletic director and he spent 10 years in that role. He also taught mathematics at Yale and Rice.

Reflecting on his NFL days, Ryan told the Los Angeles Times in 1980, “The greatest lingering malady that goes with playing pro football is the psychological aftereffects. It puts such a hype on your performance. It builds your status as a special person, so you make an assumption about life after football that is fallacious. It leads to a real dislocation between your aspirations and what you are actually capable of.

“There is a harm that comes to a person who get so absorbed in football that the fundamental values that should govern their existence are set aside. There is nothing more special than a great athlete who doesn’t think he’s special.

“I’d be a much better person if I’d spent more of my time not playing football. It’s an intensely selfish sport. I think I succumbed to a lot of that and I’m not as good a man as I could be because of it.” Video highlights

Sewell went hunting with a group in Florida’s Ocala National Forest on that day, the last of deer season.

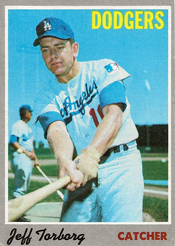

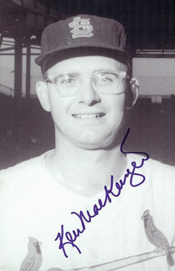

Sewell went hunting with a group in Florida’s Ocala National Forest on that day, the last of deer season. A decade later, in 1952, Miggins was in the big leagues as a rookie reserve left fielder for the Cardinals. Scully was in his third year as a Dodgers broadcaster.

A decade later, in 1952, Miggins was in the big leagues as a rookie reserve left fielder for the Cardinals. Scully was in his third year as a Dodgers broadcaster.

Doing the unexpected came naturally to MacKenzie. A hockey player from a small town on a Canadian island, he went to Yale, graduated and became a big-league pitcher.

Doing the unexpected came naturally to MacKenzie. A hockey player from a small town on a Canadian island, he went to Yale, graduated and became a big-league pitcher. In the 1940s, the Cardinals (four) and Dodgers (three) won seven of the 10 National League pennants that decade. Casey was a prominent pitcher on the Dodgers championship clubs in 1941 (14 wins, seven saves) and 1947 (10 wins, 18 saves).

In the 1940s, the Cardinals (four) and Dodgers (three) won seven of the 10 National League pennants that decade. Casey was a prominent pitcher on the Dodgers championship clubs in 1941 (14 wins, seven saves) and 1947 (10 wins, 18 saves).