When a proposed trade between the Cleveland Indians and Boston Red Sox involving Gaylord Perry hit a snag, the Cardinals swooped in and snatched the pitchers the Indians wanted.

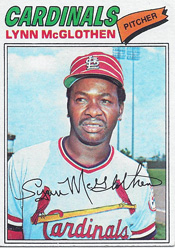

On Dec. 7, 1973, the Cardinals acquired John Curtis, Mike Garman and Lynn McGlothen from the Red Sox for Reggie Cleveland, Diego Segui and Terry Hughes. It was the second major trade between the teams since the end of the season. Two months earlier, the Cardinals got Reggie Smith and Ken Tatum from Boston for Rick Wise and Bernie Carbo.

On Dec. 7, 1973, the Cardinals acquired John Curtis, Mike Garman and Lynn McGlothen from the Red Sox for Reggie Cleveland, Diego Segui and Terry Hughes. It was the second major trade between the teams since the end of the season. Two months earlier, the Cardinals got Reggie Smith and Ken Tatum from Boston for Rick Wise and Bernie Carbo.

McGlothen was the primary reason the Cardinals made the second deal. He was thought to have the potential to be another Bob Gibson.

Louisiana lightning

At Grambling High, a public school operated by Grambling State University in Louisiana, McGlothen earned 16 varsity letters in four sports _ baseball, basketball, football and tennis. He took up tennis after trying the sport in a physical education class, according to the Des Moines Register, and became a three-time high school state singles champion.

Football, though, was the sport McGlothen liked best. Attending Grambling State games, “I grew up watching (linemen) Ernie Ladd and Buck Buchanan, wanting to play for (coach) Eddie Robinson,” he told the Register.

“I was a middle linebacker at Grambling High School, all-state (as a junior) … I thought I had a chance to play pro football,” McGlothen said to Lindsay-Schaub News Service.

He told the Register, “I didn’t have any intentions of being a (pro) baseball player.”

McGlothen was one of three top prep pitchers in north Louisiana in the late 1960s. The others: Vida Blue and J.R. Richard. McGlothen and Blue never started against one another, but McGlothen and Richard (with Lincoln High in Ruston) were opposing starters many times.

“I made it a point to save him for J.R. as much as possible,” Grambling High School baseball coach Donnell Cowan told United Press International. “Those two really had some great games during that time.”

(Richard and McGlothen were opposing starters five times in the big leagues. Richard won four of those games.)

Baseball beckons

McGlothen’s high school pitching impressed Red Sox scout Ed Scott.

(In 1951, Scott was scouting for Indianapolis of the Negro American League when he saw Hank Aaron play recreational ball in Mobile, Ala. Aaron joined the semipro team Scott managed, the Mobile Black Bears. Then on Scott’s recommendation, Indianapolis signed Aaron.)

After his high school graduation in 1968, McGlothen enrolled in summer classes at Grambling State. Soon after, based on Scott’s scouting reports, the Red Sox took McGlothen in the third round of the June 1968 draft. Unsure whether to stay in school on a football scholarship or join the Red Sox, McGlothen consulted with Dr. Ralph Waldo Emerson Jones, who was both the president of Grambling State and its head baseball coach. Jones “told me I had baseball potential,” McGlothen recalled to Lindsay-Schaub News Service.

He signed with the Red Sox and was sent to a farm club in Waterloo, Iowa. It wasn’t exactly the “Field of Dreams,” but the club did have a manager whose name seemed taken from a Hollywood script _ Rac Slider.

“He set out trying to make men out of us,” McGlothen said to the Des Moines Register. “He watched me throw and said, ‘There are a lot of things wrong, but I can teach you.’ He was like an army sergeant and I was a cocky kid who had just left home. He rode me and (pitcher) Roger Moret pretty hard, and used to take the keys to our cars away from us.

“I’d just got my bonus and paid $7,000 _ which was a lot for a car then _ for a Mustang with a powerful motor. Waterloo is not a big place. Seemed like every time I’d screech the tires at an intersection, someone would call Rac and he’d take the keys for a day.”

High hopes

At Class A Winston-Salem in 1970, McGlothen was 15-7 with a 2.24 ERA. After the season, he went to the Florida Instructional League, where he impressed Red Sox outfielder Carl Yastrzemski, who was working with the prospects. “This kid can be a real good big-league pitcher,” Yastrzemski told the Boston Globe. “Right now, he’s as good, if not better, than that (rookie Bert) Blyleven of Minnesota.”

Though McGlothen, 21, hadn’t pitched at a level above Class A in the minors, Ray Fitzgerald of the Globe wrote at spring training in 1971, “Maybe Lynn McGlothen is a potential Bob Gibson … The Red Sox feel he’s something special.”

A year later, in June 1972, McGlothen was called up to the Red Sox. His first win for them was a three-hit shutout of the Twins at Boston’s Fenway Park on July 4. Boxscore

McGlothen began the 1973 season with the Red Sox, got sent to the minors in May and was discovered to have torn cartilage in his right knee. He underwent surgery and returned to action with Class AAA Pawtucket in August. In a playoff game against the Cardinals’ Tulsa team, McGlothen pitched a two-hit shutout and held Keith Hernandez hitless.

Price is right

In October 1973, the Red Sox had trade talks with the Cleveland Indians about their ace pitcher, Gaylord Perry. The Indians wanted McGlothen and John Curtis but the Red Sox said they would not include both pitchers in a deal.

According to the Boston Globe, a compromise was reached between general managers Phil Seghi of the Indians and Dick O’Connell of the Red Sox. Boston would send Curtis and pitchers Marty Pattin and Craig Skok to Cleveland for Perry, but Indians owners Nick Mileti and Ted Bonda vetoed the deal.

Those trade talks were revived at the December 1973 baseball winter meetings. The Indians and Red Sox agreed to a swap of McGlothen and three others for Perry, the Globe reported, but, again, Nick Mileti intervened, wanting Curtis included in the trade.

Frustrated, the Red Sox fielded other proposals. When the Cardinals offered Reggie Cleveland (14-10 in 1973), the Red Sox accepted.

“Quite frankly, if we couldn’t have got McGlothen, we never would have made (the trade),” Cardinals general manager Bing Devine told the St. Louis Post-Dispatch. “On the basis of our scouts’ reports, we said, ‘No McGlothen, no deal.’ “

Devine said to The Sporting News, “McGlothen has an outstanding curve as well as a good fastball. We’ve been interested in him for some time, but until now they wouldn’t even talk to you about him.”

According to the Alabama Journal, Cardinals manager Red Schoendienst said, “When we made the trade with Boston, they tried to throw someone else in instead of McGlothen, but if the trade was to be made he had to be in.”

McGlothen, 23, was projected to join a Cardinals rotation led by Bob Gibson, 38. Reggie Smith, who played with McGlothen in Boston, said to reporter Arnold Irish, “Lynn will remind you of Bob Gibson. He works fast and throws hard.”

Strong start

In the first half of the 1974 season, McGlothen looked every bit the part of a young ace. He won 12 of his first 15 decisions with the Cardinals. On May 7, he pitched a four-hit shutout against the Reds. In the fifth inning he faced three batters _ Pete Rose, Joe Morgan and Johnny Bench _ and struck out each of them. Boxscore

“I am a fastball pitcher,” McGlothen told the Shreveport Times. “I don’t like to set hitters up. I like to set them down.”

The next month, McGlothen had a three-hit shutout versus the Padres and got three hits in a win against the Braves. Boxscore and Boxscore

“Lynn reminds me of Gibson a lot, especially the way he’s so confident of his fastball no matter what the count or the situation,” Cardinals catcher Ted Simmons told the Alabama Journal. “Like Bob, he challenges the hitter, supplements the smoke with both a big curve and slow curve, and helps himself at the plate, too.”

Named to the National League all-star team, McGlothen worked a scoreless inning against the American Leaguers and struck out Reggie Jackson. Boxscore

In his book “Reggie: A Season With a Superstar,” Jackson said, “McGlothen struck me out on three breaking balls. Breaking balls! I mean, this is the All-Star Game, man. Throw the ball and let the batter hit it. He went at it like it was the World Series. Which is why they win.”

Tragic ending

McGlothen was 16-12 with a 2.69 ERA for the 1974 Cardinals and led the club in wins and strikeouts (142). He had 15 wins in 1975 and 13 in 1976.

After the 1976 season, the Cardinals acquired a pair of potential starters, Larry Dierker and John D’Acquisto, and deemed McGlothen expendable. On Dec. 10, 1976, McGlothen was dealt to the Giants for third baseman Ken Reitz.

“I was the Cardinals’ highest-paid pitcher and I kind of figured they would trade me,” McGlothen told The Sporting News.

Over the next six years, he pitched for four clubs (Giants, Cubs, White Sox and Yankees) and finished with a career record of 86-93 (44-40 as a Cardinal). Video of McGlothen for Cubs versus Cardinals

Out of baseball, McGlothen, 34, died on Aug. 14, 1984, at Dubach, Louisiana, in a mobile home fire that also killed a woman he was visiting there, Joey Davidson of the Lincoln Parish sheriff’s office told the Shreveport Times. Davidson said the fire started about 2 a.m. in the living room of the mobile home of Gloria Reed Smith. Smith rescued her daughters, ages 13 and 7, then went back inside to help McGlothen, Davidson said.

“They were together when we found them, right at the entrance to the bedroom,” Davidson told the Shreveport Times.

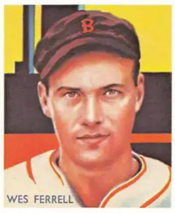

A right-hander, Ferrell holds the record for regular-season career home runs hit by a pitcher. According to baseball-reference.com, the top six are Ferrell (38), Bob Lemon (37), Warren Spahn (35), Red Ruffing (34), Earl Wilson (33) and Don Drysdale (29).

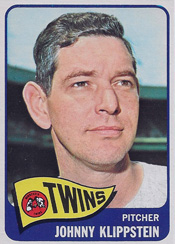

A right-hander, Ferrell holds the record for regular-season career home runs hit by a pitcher. According to baseball-reference.com, the top six are Ferrell (38), Bob Lemon (37), Warren Spahn (35), Red Ruffing (34), Earl Wilson (33) and Don Drysdale (29).  In April, he served with the National Guard, trying to quell riots in Washington, D.C. In the fall, he went to Vietnam, looking to boost the spirits of U.S. troops. In between, he pitched in relief for the Baltimore Orioles.

In April, he served with the National Guard, trying to quell riots in Washington, D.C. In the fall, he went to Vietnam, looking to boost the spirits of U.S. troops. In between, he pitched in relief for the Baltimore Orioles.

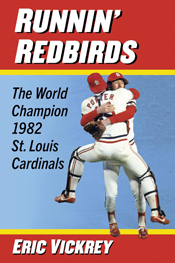

Yet, the 1982 Cardinals may be the franchise’s greatest team since baseball went to a divisional alignment. Since 1969, the only Cardinals club to finish a regular season with the best record in the National League and win a World Series title was the 1982 team.

Yet, the 1982 Cardinals may be the franchise’s greatest team since baseball went to a divisional alignment. Since 1969, the only Cardinals club to finish a regular season with the best record in the National League and win a World Series title was the 1982 team.