Whether as a player or as a coach, Maxie Baughan was good at sizing up situations and calling the shots.

An outside linebacker who played in the NFL primarily from 1960 to 1970 with the Philadelphia Eagles and Los Angeles Rams, Baughan was the captain of the defense and chose the alignment for each play during a game.

An outside linebacker who played in the NFL primarily from 1960 to 1970 with the Philadelphia Eagles and Los Angeles Rams, Baughan was the captain of the defense and chose the alignment for each play during a game.

Described by the New York Times as “one of the most fearsome linebackers of the 1960s,” Baughan was named to the Pro Bowl in nine of his first 10 seasons in the NFL. He knocked heads with the St. Louis Cardinals multiple times.

Baughan went on to have a long coaching career as an assistant in the NFL and as head coach in college at Cornell.

Ramblin’ Wreck

Baughan attended high school in Bessemer, Ala., a major steelmaking center. Recalling his boyhood days, Baughan told Gannett News Service, “I was going into the mills since as long as I can remember. I knew the first time I went in I didn’t want to work in there the rest of my life.”

(According to The Birmingham News, Baughan’s father, an electrician, died when he fell from a ladder at a coal mine near Birmingham in June 1961. He was 52. Baughan Sr. suffered a heart attack, fell onto high-voltage wires and was electrocuted, the Binghamton [N.Y.] Press and Sun-Bulletin reported.)

Maxie Baughan played football at Georgia Tech and excelled as a linebacker and center. “He’s one of the most consistently great football players I have coached,” head coach Bobby Dodd told the Philadelphia Inquirer.

(Baughan was quite a baseball fan, too. While at Georgia Tech, “I used to go all the time to old Ponce de Leon Park in Atlanta to see the [minor-league] Crackers and I loved it,” he said to The Montogmery [Ala.] Advertiser.)

Baughan graduated from Georgia Tech with a degree in industrial engineering.

As a youth, Baughan earned the Boy Scouts of America’s highest rank, the Eagle Scout Award. As a professional football player, Baughan became a Philadelphia Eagle. The team selected him in the second round of the 1960 NFL draft.

The Natural

The 1960 Eagles were a tough, talented group featuring Chuck Bednarik, Tom Brookshier, Tommy McDonald, Pete Retzlaff, Joe Robb and Norm Van Brocklin. Though a rookie, Baughan fit right in.

A brawl broke out on the field in a 1960 exhibition game between the Eagles and San Francisco 49ers. Hugh McElhenny, the 49ers running back who was nicknamed “The King” and who was destined for election to the Pro Football Hall of Fame, “was dropkicking the back of the head” of Eagles defensive tackle Ed Khayat, the Philadelphia Daily News reported.

According to the newspaper, Baughan came to Khayat’s rescue, “driving McElhenny clear across the field, pumping the heels of his hands into the veteran’s chest and finally lifting his helmet to deliver the fist de grace.”

Baughan said to the Daily News, “When I saw him kick Ed in the head, I just had to go after him.”

The rookie’s action earned him the respect of his teammates. His play as a linebacker earned him a spot as a starter. “He’s quick as a cat,” Eagles assistant coach Nick Skorich told the Daily News. “He uses his hands beautifully. He has good play sense, and he’s a hard, sharp tackler.”

Baughan looked the part, too. The Sporting News described him as “pug-nosed, weather-beaten.” Sandy Grady of the Philadelphia Bulletin put it this way: “A face that was forged in a furnace … pugnacity, intelligence and violence written on it.”

The first time he faced the St. Louis Cardinals, on Oct. 9, 1960, Baughan made 10 tackles, including seven unassisted, and broke up a pass, United Press International reported. Game stats

“He’s one of the hardest tacklers on the team, a quick thinker, fast, alert and as gung-ho as they come,” The Sporting News noted. “He took over on the starting unit as if the position had been made for him.”

The Eagles won the 1960 NFL championship, in part because of a defense that limited Vince Lombardi’s Green Bay Packers to 13 points in the title game.

L.A. story

In 1965, the Eagles opened the season against the Cardinals. With the score tied 20-20 at halftime, Baughan, captain of the defense, convinced head coach Joe Kuharich to call off the blitzes against quarterback Charley Johnson.

“We couldn’t blitz too much against them,” Baughan said to the Philadelphia Daily News. “Heck, they invented the blitz. They can pick it right up.”

Instead, with Baughan calling the defensive signals, the Eagles faked the blitz, then realigned their formation at the last instance. The jitter-bugging defense “completely confounded” Johnson, according to the Daily News. The Eagles limited the Cardinals to seven points in the second half and won, 34-27. Game stats

As the season progressed, the relationship between Baughan and Kuharich got rocky. “Near the end, the two of them were getting along like Richard Burton and Elizabeth Taylor in ‘Virginia Woolf,’ ” the Philadelphia Inquirer noted.

After the season, amid reports Baughan wanted to be traded, Los Angeles Rams head coach George Allen called Kuharich “31 times in as many days,” trying to make a deal for the linebacker, The Sporting News reported.

In April 1966, Kuharich relented. The Eagles dealt Baughan to the Rams for defensive tackle Frank Molden, linebacker Fred Brown and a draft choice. “Maxie Baughan is the best right side linebacker in the game,” Allen told The Sporting News.

In April 1966, Kuharich relented. The Eagles dealt Baughan to the Rams for defensive tackle Frank Molden, linebacker Fred Brown and a draft choice. “Maxie Baughan is the best right side linebacker in the game,” Allen told The Sporting News.

The 1966 Rams defense featured the Fearsome Foursome front line of Deacon Jones, Merlin Olsen, Rosey Grier and Lamar Lundy. Joining Baughan as the linebackers were Bill George (a future Pro Football Hall of Famer) in the middle and Jack Pardee on the left side. Another standout, Eddie Meador, was the safety.

Amid all that talent, Allen chose Baughan to be the defensive captain and entrusted him to call the plays. “As the Rams’ defensive signal caller, Baughan was responsible for some 250 different defenses and 180 audible signals,” The Sporting News reported.

Baughan told the publication, “I would say that I audibilize about 85 percent of the time. A lot of things enter into my decision, like down and distance, the hash marks, field position, the particular formation.”

The Los Angeles Times noted, “His vast knowledge of Allen’s intricate defense and execution of the many audibles from a variety of formations has made the Rams one of pro football’s most effective defensive units. Equally important is the fact Maxie is a leader and serves as an inspiration to the team.”

Baughan thrived playing for Allen. He told the Ithaca (N.Y.) Journal, “I probably learned more about football from George Allen than anyone else.”

The Sporting News called Baughan “the brains of the Rams defense” and dubbed him “The Battering Ram.”

Eventually, the battering took its toll. Baughan underwent knee surgeries after the 1967, 1968 and 1969 seasons. He suffered a concussion in a 1969 game against the Atlanta Falcons and was unconscious for almost 15 minutes, The Sporting News reported. The cumulative pain became unbearable.

“I’m allergic to some medicine, including pain killers,” Baughan told The Sporting News. “I can’t even take an aspirin. It started back in 1962 when I was with Philadelphia. I took a muscle relaxer and had a violent reaction. The Eagles’ trainer literally saved my life.”

Coaching carousel

The Rams fired Allen after the 1970 season and Baughan retired from playing. When Allen became head coach of the Washington Redskins in 1971, Baughan assisted him. That began a long second career as a coach.

Baughan was defensive coordinator at Georgia Tech for two years (1972-73). In 1974, he left to become defensive coordinator of the New York Giants, but before the season began he quit and rejoined Allen with the Redskins as a player-coach.

After stints as defensive coordinator of the Baltimore Colts (1975-79) and Detroit Lions (1980-82), Baughan became head coach at Cornell. He was recommended for the job by former Colts running back Tom Matte, who became a friend of Baughan when he was with Baltimore. Matte had connections to an influential almnus at Cornell.

Replacing Bob Blackman, who retired, Baughan coached six seasons (1983-88) at Cornell. The Ivy League program had losing records his first three seasons, then finished 8-2, 5-5 and 7-2-1 the last three seasons.

In April 1989, the Ithaca Journal reported a rift between Baughan and assistant coach Peter Noyes stemmed from a romantic relationship between Baughan and Noyes’ wife. Citing “personal tensions” for his decision, Baughan resigned.

He went on to be linebackers coach for the Minnesota Vikings (1990-91), Tampa Bay Buccaneers (1992-95) and Baltimore Ravens (1996-98). Among the linebackers he coached were standouts Derrick Brooks of the Buccaneers and Ray Lewis of the Ravens.

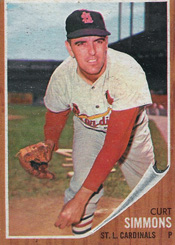

From Sept. 1 to Sept. 13, Simmons won four starts in a row for the 1963 Cardinals and pitched three consecutive shutouts in that stretch.

From Sept. 1 to Sept. 13, Simmons won four starts in a row for the 1963 Cardinals and pitched three consecutive shutouts in that stretch. On Aug. 29, 1973, the Cardinals purchased the contract of Fisher, 37, from the White Sox. The right-handed knuckleball specialist was in his 15th and final season in the majors.

On Aug. 29, 1973, the Cardinals purchased the contract of Fisher, 37, from the White Sox. The right-handed knuckleball specialist was in his 15th and final season in the majors. Both of his legs were broken, just under the knees, and he broke his pelvis, too, according to the Globe.

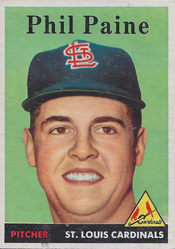

Both of his legs were broken, just under the knees, and he broke his pelvis, too, according to the Globe. At Hartford in 1951, Paine was managed by Tommy Holmes, the former Braves outfielder who twice led the National League in hits. When Braves manager Billy Southworth resigned in June 1951, Holmes replaced him.

At Hartford in 1951, Paine was managed by Tommy Holmes, the former Braves outfielder who twice led the National League in hits. When Braves manager Billy Southworth resigned in June 1951, Holmes replaced him. On Aug. 27, 1963, at Candlestick Park in San Francisco, Mays capped a two-month hot streak with his 400th career home run for the Giants.

On Aug. 27, 1963, at Candlestick Park in San Francisco, Mays capped a two-month hot streak with his 400th career home run for the Giants. When he felt overwhelmed, he walked out on his team. He did that multiple times in stints with the Padres, Giants and Astros.

When he felt overwhelmed, he walked out on his team. He did that multiple times in stints with the Padres, Giants and Astros.