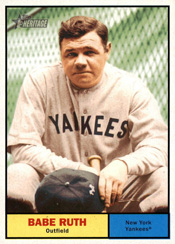

The Sultan of Swat struck out in his bid to become St. Louis Browns manager.

After finishing last in the eight-team American League in 1937, the Browns were looking for a manager and Babe Ruth wanted the job.

After finishing last in the eight-team American League in 1937, the Browns were looking for a manager and Babe Ruth wanted the job.

Considering that the Browns drew a total home attendance of 123,121 in 1937, Ruth’s willingness to manage the team in 1938 seemed a special opportunity to infuse interest in the moribund franchise, but his overture was rejected.

Manager material?

Approaching his final years as a player, baseball’s home run king wanted to manage in the majors. Ruth and Yankees manager Joe McCarthy, who took over the club in 1931, didn’t get along. Ruth began campaigning for the job, but Yankees general manager Ed Barrow was happy with McCarthy and uninterested in Ruth as a field leader.

In his book, “Babe: The Legend Comes to Life,” author Robert Creamer noted, “Ruth’s obtuseness about the Yankees managing job was almost pitiful. It was obvious Barrow was convinced he was incapable of managing.”

Other clubs thought differently. Opportunities developed for Ruth to manage the Red Sox, Tigers and Athletics, but plans went haywire.

In the summer of 1932, when the Red Sox were on their way to a 43-111 record (and Ruth, with 41 home runs, was powering the Yankees to a pennant), they talked to him about becoming player-manager, but “Babe did not want to leave” New York, Creamer reported. “The Red Sox post came up again in 1933 when Tom Yawkey bought the club. Yawkey wanted to hire Ruth but was persuaded not to by general manager Eddie Collins.”

After the 1933 season, according to Creamer, “the Tigers definitely wanted him. Tigers attendance had been declining and club owner Frank Navin felt Ruth as player-manager would help the gate and possibly help the team.”

The Yankees agreed to a deal. They “were looking for a way to dump Ruth gracefully and this seemed an ideal situation,” Creamer reported.

Navin asked Ruth to come to Detroit to work out the details, but when Ruth left instead for a planned trip to Hawaii, Navin became annoyed and changed his mind. He acquired Mickey Cochrane from the Athletics to be player-manager. (Cochrane led the Tigers to the 1934 pennant and a World Series berth against the Cardinals.)

The Yankees offered to make Ruth manager of their Newark farm club, but he told them he didn’t want to go to the minor leagues, Creamer reported.

Ruth, 39, stayed with the Yankees in 1934, hit 22 home runs and lobbied to become their manager, but club owner Jacob Ruppert reaffirmed his commitment to Joe McCarthy. An angry Ruth told Joe Williams of Scripps-Howard’s New York World-Telegram, “I’m through with the Yankees. I won’t play with them again unless I can manage. They’re sticking with McCarthy, and that lets me out.”

Amid the hullabaloo his comments caused in Gotham, Ruth said sayonara and left with an all-star team for a goodwill tour of Japan. Connie Mack, who owned and managed the Athletics, was leader of the tour, but Ruth was given the chance to manage the all-star team.

According to Creamer, Mack, nearing 72, was considering stepping down as Athletics manager “and liked the idea” of Ruth replacing him. “Ruth’s presence would help the sagging gate, and Connie had always got along well with Babe,” Creamer noted.

Mack used the Japan tour as a test to see how Ruth would do as manager, but Babe got a failing grade, in part, because he feuded with teammate Lou Gehrig, creating divisions among the all-star group.

Promises, promises

In February 1935, soon after Ruth turned 40, the Yankees released him so that he could accept an offer from the Braves to become team vice president, assistant manager and player. Ruth accepted the proposal because he was convinced Braves owner Emil Fuchs intended to make him the manager in 1936, replacing Bill McKechnie.

Early in the 1935 season, though, Ruth became disenchanted. As Creamer noted, “His duties as vice-president seemed confined to attending store openings and other such affairs to get the publicity Fuchs said the club needed. As assistant manager, all he did was tell McKechnie when he was able to play. He soon found out Fuchs had no intention of forcing McKechnie out to make way for Babe.”

On June 2, 1935, Ruth quit the Braves. “I’d still like to manage,” he told columnist Grantland Rice, “but there’s nothing in sight.”

Support for Babe

Two years later, though no offers had come to him, Ruth still was determined to manage in the majors. The Browns looked to be a possibility.

In July 1937, Browns manager Rogers Hornsby was fired and replaced by another former Cardinals player, Jim Bottomley, who had no managing experience. Former Cardinals manager Gabby Street was hired to be a coach on Bottomley’s staff and provide him with on-the-job training.

The Browns, 25-52 with Hornsby, were 21-56 with Bottomley and finished 46-108, 56 games behind the champion Yankees. “We had two managers in 1937, and we thought we made the right guess each time, yet we finished in last place,” Browns general manager Bill DeWitt Sr. told the St. Louis Star-Times.

According to Sid Keener of the Star-Times, DeWitt and Browns owner Donald Barnes “have been advised by stockholders and friends to make a big play for important publicity by hiring none other than George Herman Ruth, The Babe himself” to be the next manager.

“Ruth would have a powerful magnet at the box office _ at the start, anyway,” Keener advised. “The Babe, back in a major-league uniform as manager of the Browns, would go over in a big way for publicity.”

Advocating for the hiring of Ruth, John Wray of the St. Louis Post-Dispatch wrote, “Some club might do worse than give The Bambino a workout. It could not go broke with a one-year experiment. The Bambino’s name might have some pulling power at the gate _ for a while.”

Wray’s Post-Dispatch colleague, L.C. Davis, suggested that choosing Ruth to manage “would make the turnstiles play a merry tune.”

Babe makes his pitch

In an interview with author William B. Mead for the 1978 book, “Even the Browns,” DeWitt (father of 2023 Cardinals owner Bill DeWitt Jr.) recalled, “Babe Ruth called me up. Out of the blue. I didn’t know him. Never met him. He said, ‘Hey, kid, this is Babe Ruth. I know you haven’t got a good ballclub, but I’d like to be your manager. I can’t get a job managing anyplace else, so I’d like to be the manager of the Browns.’

“I said, ‘Now, let me think about it. We’ve just about made up our minds on a guy. Let me talk to some people.’ I took his phone number.”

The guy Barnes and DeWitt wanted for the job was Gabby Street, not Ruth.

Regarding Ruth, DeWitt told Mead, “He would be a great attraction for a year, but we’d probably have to pay him a pretty good salary, and at the end of the year his attractiveness is gone. We had a lousy ballclub, and you know he’s not going to be a good manager, and we were going to try to develop some young players. So we decided not to do it.”

Barnes told the Star-Times, “We did not consider Ruth for a moment. Ruth is a great name in baseball _ or, was a great name _ but, after all, the public will only pay to see a winning ballclub.”

In comments to the Post-Dispatch, Barnes said, “We never had an idea of seeking Ruth as manager at any time. He is not the type we believe would make a successful leader.”

Sid Keener concluded in the Star-Times, “Ruth’s salary demand is considered the major stumbling block in his behalf. George Herman, no doubt, would request a contract calling for a salary in the neighborhood of $30,000.”

According to the Post-Dispatch, Joe McCarthy of the Yankees and Bill Terry of the Giants were the highest-paid managers. Each made $35,000.

Oscar Melillo, a former Browns second baseman who would become a coach for them in 1938, wanted Ruth to be their manager and told the New York Daily News, “Whatever the Browns paid Ruth would be back in the till the first time they played the Yankees in New York.”

Ruth said to the New York Journal-American, “The way I look at it, it must be because those owners want to keep the small-salaried guys in there as long as the public will stand for it.”

Street signed a one-year contract with the Browns for between $7,500 and $10,000, the Star-Times reported. The 1938 Browns were 53-90 when Street was replaced by Melillo with 10 games left in the season.

Missing out

In June 1938, the Dodgers hired Ruth, 43, to be a coach on the staff of manager Burleigh Grimes. It was a publicity stunt, but Ruth hoped it might put him in position to take over for Grimes. Instead, Leo Durocher replaced Grimes after the season and Ruth was out of a job. The chance to manage never came.

“I think I’d make a good manager,” Ruth told Jimmy Powers of the New York Daily News. “I’ve followed the game closely. I know men, I know batters, and I know pitchers.”

In his biography of Ruth, Robert Creamer wrote, “Could he have managed? Of course. Ruth had certain obvious qualities. He was baseball smart, he was sure of himself, he was held in awe by his fellow players and he was undeniably good copy. He may not have been a success _ most managers are not _ but he should have been given the chance.”

Duke Carmel certainly fit the part. He was named after Duke Snider, had the mannerisms of Ted Williams and could hit with the power of Mickey Mantle.

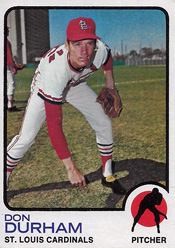

Duke Carmel certainly fit the part. He was named after Duke Snider, had the mannerisms of Ted Williams and could hit with the power of Mickey Mantle. A rookie right-hander with St. Louis in 1972, Durham had as many home runs (two) as wins (two). He batted .500 (seven hits in 14 at-bats) and had a slugging percentage of .929.

A rookie right-hander with St. Louis in 1972, Durham had as many home runs (two) as wins (two). He batted .500 (seven hits in 14 at-bats) and had a slugging percentage of .929. On July 10, 1923, Stuart started both games of a doubleheader for the Cardinals against the Braves and earned complete-game wins in both.

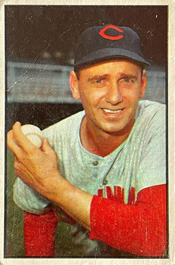

On July 10, 1923, Stuart started both games of a doubleheader for the Cardinals against the Braves and earned complete-game wins in both. A left-hander who relied on pinpoint control and an assortment of breaking pitches, Raffensberger faced the Cardinals a lot _ 79 times, including 59 starts. He lost (34 times) more than he won (23 times) versus St. Louis, but when he was good he was nearly unhittable.

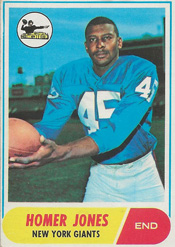

A left-hander who relied on pinpoint control and an assortment of breaking pitches, Raffensberger faced the Cardinals a lot _ 79 times, including 59 starts. He lost (34 times) more than he won (23 times) versus St. Louis, but when he was good he was nearly unhittable. A receiver with the 1960s New York Giants, Jones was a master at producing long gains. He did it either one of two ways _ hauling in deep passes, or using his deft footwork to add yardage after a grab. His career average of 22.3 yards per catch is a NFL record.

A receiver with the 1960s New York Giants, Jones was a master at producing long gains. He did it either one of two ways _ hauling in deep passes, or using his deft footwork to add yardage after a grab. His career average of 22.3 yards per catch is a NFL record.