Pitcher Neil Allen was given a mission impossible of sorts in his first assignment with the Cardinals.

Having worn out his welcome in New York, Allen felt instantly unwelcomed in St. Louis when the Cardinals acquired him and pitcher Rick Ownbey from the Mets for first baseman Keith Hernandez on June 15, 1983. When the crowd attending a game at Busch Memorial Stadium heard about the deal, they booed.

Having worn out his welcome in New York, Allen felt instantly unwelcomed in St. Louis when the Cardinals acquired him and pitcher Rick Ownbey from the Mets for first baseman Keith Hernandez on June 15, 1983. When the crowd attending a game at Busch Memorial Stadium heard about the deal, they booed.

Being traded for Hernandez _ a World Series hero, Gold Glove winner and league MVP _ was challenge enough for Allen. The Cardinals increased the degree of difficulty by having him make his debut for them against Hernandez and the Mets.

Though Allen made a good first impression, it wasn’t a lasting one.

Under pressure

A right-hander from Kansas City, Kan., Allen was 21 when he earned a spot on the Mets’ Opening Day roster in 1979. He flopped as a starter, moved to the bullpen and flourished as a reliever. His first big-league win came against the Cardinals. Boxscore

Entrusted with the closer role, Allen ranked among the top six in saves in the league for three consecutive seasons (1980-82). The New York Times described him as “the life of the locker room, endearing but hyperactive and volatile.”

Trouble developed in 1983. In his second appearance of the season, Allen gave up a game-winning single. The next night, after he allowed a walkoff grand slam to the Phillies’ Bo Diaz, Allen “stalked off the mound, flung his glove into the dugout and then sat there with his head in his hands for fully five minutes, the tears flowing like a faucet,” the New York Daily News reported. Boxscore

From there, the Mets went to St. Louis for a series with the Cardinals. Allen got involved in a barroom fracas across the river in Illinois, told Mets management he had a drinking problem and asked for help. He was sent to a specialist, who determined Allen’s problem was stress, not alcohol, The Sporting News reported.

(Allen later told the New York Times he knew he didn’t have an alcohol problem. “I was talking out of desperation,” he said. “I’m ashamed of myself for saying it … What I had was an emotional problem.”)

Nothing was wrong with his arm though. The Mets discovered there was a trade market for him, and the Cardinals made the best offer.

Strong start

The Cardinals had a closer, Bruce Sutter, but needed a starter, so manager Whitey Herzog put Allen in the rotation. His first appearance came on June 21, 1983, against the Mets at New York’s Shea Stadium.

Allen pitched eight scoreless innings and got the win. He struck out Hernandez twice and held him hitless. Boxscore

“That was vintage Neil Allen,” Hernandez said to the Daily News. “That was one of the best curves I’ve faced in eight years in the league.”

Allen told the St. Louis Post-Dispatch, “I felt like I had a lot to prove. Everybody thought the trade was so outrageous. To be honest, I thought so at first, too.”

Allen also got his first career RBI in the game. His squeeze bunt scored Ozzie Smith from third. “I couldn’t believe I got it down,” Allen told the Post-Dispatch.

In the groove

Nine days later, in St. Louis, Allen beat the Mets again. The only run he allowed came on a Jose Oquendo RBI-single. Allen again held Hernandez hitless.

Allen also got another RBI, lining a Walt Terrell pitch off the outfield wall for a double. “I floated that one in at about 50 mph,” Terrell told the Post-Dispatch.

Thinking the ball would carry over the wall, Allen went into a home run trot. “I never hit a ball like that in my life,” Allen said to the newspaper. “I took a lot of kidding for my home run trot.” Boxscore

In July, Allen pitched shutouts in consecutive starts versus the Padres and Dodgers, giving him a 5-1 record and 2.02 ERA with St. Louis. Boxscore and Boxscore

Then he lost four consecutive decisions and was moved back to the bullpen before returning to the rotation in September.

On Sept. 14, Allen beat the Mets for the third time, winning a matchup with Tom Seaver. Boxscore

Allen was 3-0 with an 0.87 ERA against the Mets in 1983. Overall for the Cardinals, he was 10-6.

Another adjustment

The Cardinals rewarded Allen with a four-year contract. At 1984 spring training. Herzog named him to the starting rotation, then changed his mind. With the 1983 Cardinals, Allen’s ERA as a reliever (1.88) was better than it was as a starter (3.94). “Neil has been a good starter, but I think he’ll be an excellent reliever,” Herzog told The Sporting News.

Another factor in Herzog’s decision was Allen’s inability to develop a changeup or to mix pitches during a game. “In short relief, he can get by with just his fastball and big breaking curve _ more power than brainpower,” The Sporting News noted.

Allen told the publication, “I’m not your ideal brain surgeon. if I start worrying about what’s in my noodle, what I have there, then I’ll be in real trouble.”

He said to the Post-Dispatch, “I don’t have the pitches for a starting pitcher. And, if I did, I’m still too hyper. I’ve got to have the ball, and if I die out there, I’ve got to have the ball again tomorrow or I go berserk. If I don’t get the ball except every fifth day or so, I go crazy.”

With Bruce Sutter established as the closer, Allen took a setup role with the 1984 Cardinals. In 56 relief appearances, he was 9-5 with three saves.

Wrong role

Sutter, who had 45 saves for the 1984 Cardinals, became a free agent and went to the Braves. Herzog named Allen the closer. Asked about replacing Sutter in 1985, Allen told The Sporting News, “Nobody but God can get 45 saves, and God is in Atlanta. If I can do half, I’ll be happy.”

Post-Dispatch columnist Kevin Horrigan wrote, “The fact remains that unless Neil Allen does the job _ two dozen saves or more _ the Cardinals will be lucky to stay out of the National League East basement.”

The Cardinals opened the 1985 season at New York against the Mets and it was a disaster for Allen. On Opening Day, he gave up a game-winning home run to Gary Carter. The next day, the Mets won when Allen walked Danny Heep with the bases loaded. Boxscore and Boxscore and Video

“I didn’t use the right psychology,” Herzog told the Post-Dispatch. “I was trying to get him past the first one and I doubled the whammy.”

In his book “White Rat: A Life in Baseball,” Herzog said, “His confidence was shot. A relief pitcher without confidence is like tits on a boar hog.”

Allen said to the Post-Dispatch, “Mentally, I was messed up.”

In 22 appearances for the 1985 Cardinals, Allen was 1-4, with two saves and a 5.59 ERA. In June, they sent him to the Yankees. According to the Post-Dispatch, Herzog told Yankees manager Billy Martin, “He can help you if he can get his head on straight.”

Cardinals pitcher Joaquin Andujar told the newspaper, “Someone with a weak mind, like Neil Allen, will go into a slump for two months. If he had a strong mind, I think Neil Allen would be pitching good. He gives up too easy.”

In his book, Herzog said, “Neil Allen, a fine young man with a live arm and a great curveball, kept expecting disaster to strike, and it usually did.”

The Cardinals, who called up rookie closer Todd Worrell in late August, won the 1985 pennant.

Allen went on to pitch for the Yankees (1985, 1987-88), White Sox (1986-87) and Indians (1989). His career record: 58-70, 75 saves. In three years with the Cardinals, he was 20-16 and five saves.

Allen was pitching coach on the staff of Twins manager Paul Molitor from 2015-17.

Soon after, when the crack turned into a chasm, the Phillies fell and the Cardinals climbed past them to win the 1964 pennant.

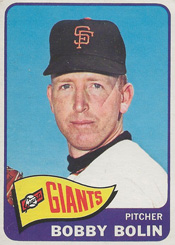

Soon after, when the crack turned into a chasm, the Phillies fell and the Cardinals climbed past them to win the 1964 pennant. A right-hander with a fastball rated among the best in the National League, Bolin was effective both as a starter and a reliever.

A right-hander with a fastball rated among the best in the National League, Bolin was effective both as a starter and a reliever. Pena worked his wizardry for the Cardinals after they acquired him from the Orioles for cash on June 15, 1973.

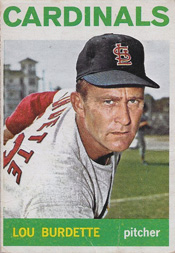

Pena worked his wizardry for the Cardinals after they acquired him from the Orioles for cash on June 15, 1973. On June 15, 1963, the Cardinals obtained Burdette, 36, from the Braves for catcher

On June 15, 1963, the Cardinals obtained Burdette, 36, from the Braves for catcher  On June 6, 1933, Dean and Derringer got into a fight on the field before a game at Cincinnati. Only their egos got bruised.

On June 6, 1933, Dean and Derringer got into a fight on the field before a game at Cincinnati. Only their egos got bruised.