Russ Van Atta, a left-handed pitcher fresh off a promising start in the majors, earned a noble, but costly, save.

After an impressive rookie season with the 1933 Yankees, Van Atta injured his pitching hand when he rescued his dog from a house fire.

No longer able to control a curveball, his performance waned and he got sent from the Yankees to the St. Louis Browns.

Iron man

Born in the northwestern New Jersey community of Augusta, Van Atta turned 14 in 1920, the year his father died of typhoid fever, he told the Morristown (N.J.) Daily Record. Van Atta said he went to work in a local zinc mine. “I worked at the 700-foot level and I made 57 cents an hour,” he said to the Morristown newspaper.

Van Atta also excelled in local baseball games and the owner of the mine helped him get an athletic scholarship to Penn State. In 1928, Yankees scout Paul Krichell, who signed Lou Gehrig, Leo Durocher and Tony Lazzeri, got Van Atta, 22, a bonus offer of $250.

After five seasons in the minors, Van Atta was nearly 27 when he made the Yankees’ Opening Day roster in 1933, joining a starting rotation that included Lefty Gomez and Red Ruffing.

Welcome to the show

On April 25, 1933, Van Atta made his big-league debut with a start against the Senators at Washington.

The starting lineups were loaded with future Hall of Famers _ center fielder Earle Combs, third baseman Joe Sewell, right fielder Babe Ruth, first baseman Lou Gehrig, second baseman Tony Lazzeri and catcher Bill Dickey for the Yankees; left fielder Heinie Manush, right fielder Goose Goslin and shortstop Joe Cronin for the Senators. (Another, Senators outfielder Sam Rice, entered the game in the ninth.)

Van Atta shined amid the stellar cast. He pitched a five-hit shutout and produced four singles and a sacrifice bunt in the Yankees’ 16-0 victory. Years later, he told The Montana Standard, a newspaper in Butte, that “the greatest thrill was going 4-for-4.”

Stealing the spotlight, though, was the brawl that occurred in the fourth inning after the Yankees’ Ben Chapman slid hard into second, knocking down the Senators’ Buddy Myer. As several players fought, “hundreds of fans came pouring out of the lower tier” of the stands and joined in a “pitched battle,” the New York Times reported. Five spectators were arrested, and three players (Chapman and Dixie Walker of the Yankees, and Myer) were ejected. Boxscore

Outdoors with the Babe

Van Atta relished being a member of the Yankees and was especially fond of Babe Ruth and manager Joe McCarthy.

“Babe came down (to New Jersey) one time for a turkey hunt,” Van Atta recalled to the Morristown Daily Record. “It was supposed to be a wild turkey hunt, but the turkey was actually a tame one that weighed about 36 pounds. The turkey was on an oak tree and Babe was supposed to be the guy who shot it, but his first shell jammed. Finally, he put another shell in the gun and he put the buckshot through the turkey, and we carried the turkey to (the) house.”

Van Atta said Ruth took the bird to the Fulton Fish Market in New York to get it cleaned, then served it for dinner at his apartment.

Regarding Joe McCarthy, Van Atta told the Morristown newspaper, “He knew the game like no one else alive.”

Van Atta completed his rookie season with a 12-4 record and a .283 batting average. His .750 winning percentage tied him with Lefty Grove of the Athletics for best among American League pitchers in 1933.

Good deed

At 2;30 a.m. on Dec. 13, 1933, Van Atta was awakened at his Mohawk Lake, N.J., home by his wife, who discovered the house was on fire, Van Atta recalled to the Montana Standard.

In addition to Van Atta and his wife, others in the house were their child and Van Atta’s mother, United Press reported. All escaped, but then Van Atta realized his cocker spaniel pup still was in the burning house, the St. Louis Star-Times reported.

Van Atta rushed back into the building and grabbed the dog, “but in trying to get back out he smashed into a glass door,” the Star-Times reported. Among his injuries was a severed nerve on the index finger of his pitching hand.

The index finger went numb and Van Atta said he never recovered any sense of feeling in the digit. (More than 40 years later, Van Atta lit a match under the finger and held it there without flinching to demonstrate to a newspaper reporter that the numbness remained.)

Van Atta kept the injury a secret from the Yankees, the Montana Standard reported.

Without any feeling in the index finger, Van Atta couldn’t control the curveball. “I had a good fastball and I still had the curve, but I never knew where the curve would go,” he told the Montana newspaper. Batters “started laying for my fastball,” he said.

Van Atta was 3-5 with a 6.34 ERA for the 1934 Yankees. In May 1935, his contract was sold to the Browns

Change of scene

Going from the Yankees, who never had a losing season during the 1930s, to the Browns, who never had a winning season during that decade, was a step down in every regard.

“When the Yankees traveled (by train), they had two sleeping cars for the players and only used the bottom berths,” Van Atta told the Montana Standard. “The Browns had one sleeping car, and the players had to use both the upper and lower berths.”

Fortunately for Van Atta, the Browns were desperate for pitching, and they gave him plenty of work. He led American League pitchers in appearances (58) in 1935, but was 9-16 with a 5.34 ERA.

In 1936, Van Atta again appeared in the most games (52) among American League pitchers, but was 4-7 with a 6.60 ERA.

On June 10, 1937, Van Atta tore a ligament in his pitching arm while trying to complete a game against the Senators. He didn’t win again for the rest of the season. During the winter, he underwent an elbow operation.

In his first start in 1938, Van Atta was pitted against Cleveland’s Bob Feller. For four scoreless innings, he “matched Feller pitch for pitch,” the St. Louis Globe-Democrat reported, then was knocked out of the game when struck in the left forearm by a Lyn Lary line drive. “Desperately, Van Atta tried to keep on pitching but he could barely lift the arm,” the newspaper observed. Boxscore

Van Atta sat out most of the 1939 season. At spring training with the Browns in 1940, he called it quits at 33. “I can’t throw right, so there’s no use wasting my time and the club’s money,” he told the Star-Times.

In seven years in the majors, Van Atta was 33-41 overall and 21-37 after the house fire.

Reflecting on the turn his career took after injuring his finger in the rescue of his dog, Van Atta good-naturedly told the newspaper, “I still got him, and every time I look at him I say, ‘There goes $100,000.’ “

According to the Morristown Daily Record, Van Atta was elected sheriff and then freeholder (or commissioner) in New Jersey’s Sussex County. He owned seven Gulf Oil service stations there from 1950-71.

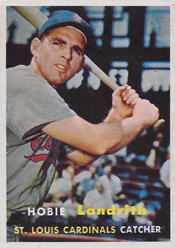

At 5-foot-8, according to the Associated Press and his Topps baseball card, Landrith stood “about as tall as the bat boy,” the Baltimore Sun noted, but he played in the majors for 14 seasons, including two with the Cardinals.

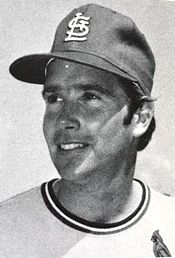

At 5-foot-8, according to the Associated Press and his Topps baseball card, Landrith stood “about as tall as the bat boy,” the Baltimore Sun noted, but he played in the majors for 14 seasons, including two with the Cardinals. In 1973, the Cardinals threw a lifeline to Foster, inviting him to spring training as a non-roster pitcher. He made the most of the opportunity, earning a spot on the Opening Day pitching staff and working his way into the starting rotation.

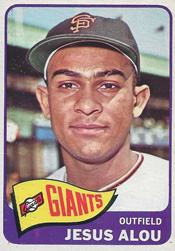

In 1973, the Cardinals threw a lifeline to Foster, inviting him to spring training as a non-roster pitcher. He made the most of the opportunity, earning a spot on the Opening Day pitching staff and working his way into the starting rotation. A perfect throw by Alou in a game against the Cardinals nailed Uecker at the plate, aiding a win for the Giants that moved them into sole possession of first place in the 1964 National League pennant race.

A perfect throw by Alou in a game against the Cardinals nailed Uecker at the plate, aiding a win for the Giants that moved them into sole possession of first place in the 1964 National League pennant race. Mike Mitchell has written the definitive Harry Caray biography, “Holy Cow St. Louis!” An entertaining and informative read, the book is

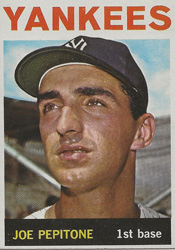

Mike Mitchell has written the definitive Harry Caray biography, “Holy Cow St. Louis!” An entertaining and informative read, the book is  Pepitone got hit by a Bob Gibson pitch at a key moment in Game 2, lined a ball that struck Gibson in Game 5, and belted a grand slam in Game 6.

Pepitone got hit by a Bob Gibson pitch at a key moment in Game 2, lined a ball that struck Gibson in Game 5, and belted a grand slam in Game 6.