Born and raised in St. Louis, Dave Nicholson was one of baseball’s all-time best power-hitting prospects, but the Cardinals were unwilling to pay the price it took to sign the hometown slugger.

In January 1958, Nicholson was 18 when he signed with the Orioles for more than $100,000, a shocking sum for an amateur at that time.

In January 1958, Nicholson was 18 when he signed with the Orioles for more than $100,000, a shocking sum for an amateur at that time.

A right-handed batter, he was “probably the hottest prospect in the country,” the Cleveland Plain Dealer reported.

Though he went on to hit some mighty home runs in the majors, the records Nicholson set were for striking out. As Frank Hyland of the Atlanta Constitution noted, Nicholson “turned around the can’t-miss label. He could miss, and did almost every opportunity.”

An outfielder, Nicholson played seven seasons in the majors with the Orioles, White Sox, Astros and Braves.

Special talent

At 6-foot-3, 215 pounds, strong and swift, Nicholson attracted pro scouts to St. Louis to see him play in amateur leagues and for Southwest High School. “He has power, physique, the arm and speed,” White Sox farm director Glen Miller told the Chicago Tribune. “His hands are as big as hams.”

The Cardinals scouted Nicholson for two years, The Sporting News reported.

In the summer of 1957. when Nicholson was playing in the amateur Ban Johnson League after his junior season in high school, Orioles scout and former Cardinals catcher Del Wilber tracked him. “Best prospect I’ve ever seen,” Wilber told the St. Louis Globe-Democrat.

The Orioles sent seven scouts at various times to St. Louis to verify Wilber’s glowing reports on Nicholson. All liked what they saw. Paul Richards, who had the dual role of general manager and manager of the Orioles, and his pitching coach Harry Brecheen, the former Cardinal, showed up, too. They put Nicholson through a special workout, with Brecheen pitching to him. Nicholson passed the test, according to the Globe-Democrat.

By the end of the summer, scouts from every big-league team had come to see the teen who crushed baseballs with the power of a hulk.

Your bid

In the fall of 1957, Nicholson, a senior, dropped out of high school and took a job with a St. Louis printer for $60 a week, the Baltimore Sun reported. According to the Chicago Tribune, Nicholson withdrew from school because of a disagreement with a coach who wanted him to play football. The Sporting News reported he left because of “weakness in the classroom.”

The pro scouts didn’t care. Every big-league team, except the Tigers, made Nicholson an offer, the Associated Press reported. It put the teen and his parents in a strong negotiating position. They let the clubs drive up the bidding in visits to the family’s Arthur Avenue home.

The Cardinals dropped out when the price reached $60,000, the Globe-Democrat reported. The Yankees didn’t stick around long either. Their scout, Lou Maguolo, who signed the likes of Tony Kubek, Norm Siebern and Lee Thomas, told The Sporting News, “Nicholson struck out seven times in 10 trips when I saw him, and I can’t recommend anybody like that.”

When the bidding reached six figures, three teams were left in the running: Cubs, Orioles, White Sox. According to The Sporting News, the Cubs and White Sox made the highest offers, but Nicholson said he chose the Orioles because, “I like Paul Richards, and I honestly think the quickest road to the majors is through the Orioles’ farm system.”

In addition to the bonus of more than $100,000 (published estimates of the amount ranged from $107,000 to $150,000), the deal included two new Pontiacs _ one for Dave and one for his father, Larry, The Sporting News reported. Larry Nicholson also was given a part-time scouting job with the Orioles.

According to the Globe-Democrat, the only other baseball amateurs to get signing bonuses of $100,000 or more were Paul Pettit (Pirates, 1950), St. Louisan Frank Baumann (Red Sox, 1952) and Hawk Taylor (Braves, 1957). Nicholson “is worth every penny,” White Sox scout Pat Monahan told the Globe-Democrat.

Learning curve

A month after signing, Nicholson was at the Orioles’ spring training camp in Scottsdale, Ariz. Watching him in batting practice, Richards told The Sporting News, “He has as much bat speed as I have seen in a youngster.”

The quick bat didn’t result too often in contact, especially against breaking pitches. Nicholson struck out in seven of his first eight at-bats in spring training games, The Sporting News reported. His only hit in 11 at-bats in exhibition games was a home run against the Giants’ Curt Barclay.

“The kid’s stance is too wide,” Cubs hitting coach Rogers Hornsby told The Sporting News. “He has to do it all with his arms, and the breaking stuff will give him a fit.”

Richards planned to have Nicholson start his pro career at the Class D level of the minors, but changed his mind and sent him to Class A Knoxville. After 25 games, he was dropped to Class B Wilson, N.C. He struggled there, too, and was demoted to Class D Dublin, Ga.

The Dublin club was managed by a St. Louisan who spent six years playing in the Cardinals’ farm system, Earl Weaver. His task was to restore Nicholson’s sagging confidence. “He has the tools to make the majors,” Weaver told The Sporting News. “He just has to get the experience to catch up with the other boys.”

Nicholson’s combined numbers for the 1958 season were 98 hits (15 for home runs) and 158 strikeouts.

The Orioles assigned Nicholson, 19, to Class AA Amarillo in 1959, and again it was a mistake. Overmatched, he was dispatched to the Class C Aberdeen (S.D.) Pheasants and put under the care of their manager, Earl Weaver.

Weaver got Nicholson to relax and play loose. Nicholson responded, producing 35 home runs and 119 RBI for Aberdeen. When injuries depleted the Pheasants’ pitching staff, Weaver had Nicholson take some turns on the mound. In nine pitching appearances, including two starts, Nicholson was 3-1 with a 2.91 ERA. He struck out 43 batters in 34 innings.

Swishing sound

Nicholson, 20, began the 1960 season with Class AAA Miami, then was called up to the Orioles in May. He batted .186 and struck out 48 percent of the time (55 whiffs in 113 at-bats) in his first big-league season.

After another year in the minors in 1961, Nicholson was with the Orioles in 1962. He batted .173 and struck out 44 percent of the time (76 whiffs in 173 at-bats).

The Orioles dealt Nicholson, Ron Hansen, Pete Ward and Hoyt Wilhelm to the White Sox for Luis Aparicio and Al Smith in January 1963. The White Sox made Nicholson their left fielder. He hit 22 home runs for them in 1963, but struck out 175 times, a major-league record.

Just six years earlier, the batter who fanned the most times in the American League in 1957 was the Senators’ Jim Lemon, with 94. As The Sporting News noted, “It wasn’t too long ago when the total of 100 strikeouts in any one season was considered staggering … but those days are gone, perhaps never to return.”

(Today, the major-league record for striking out the most times in a season is held by Mark Reynolds, 223 whiffs with the 2009 Diamondbacks. At least Reynolds hit 44 home runs that year. In 2011, Drew Stubbs of the Reds struck out 205 times and hit 15 homers. According to baseball-reference.com, the career big-league salaries paid to those players: $30 million to Reynolds and $15 million to Stubbs.)

Playing hardball

On May 6, 1964, in the first game of a doubleheader at Comiskey Park in Chicago, Athletics starter Moe Drabowsky threw a slider to Nicholson on a 2-and-1 count. Nicholson launched a towering shot that disappeared over the roof covering the upper deck in left and landed in nearby Armour Square Park. White Sox officials estimated the ball carried 573 feet, the Chicago Tribune reported.

The ball was retrieved by 10-year-old Michael Murillo Jr., who was listening to the game on his radio while his father was at softball practice in the park, the Tribune reported. In exchange for the home run ball, Nicholson gave Michael an autographed baseball and one of his bats.

Some witnesses in the upper deck said the ball cleared the roof on a fly; others said it hit atop the roof, then skidded out of the ballpark. Regardless, Nicholson joined Jimmie Foxx, Mickey Mantle and Eddie Robinson as the only players to propel a home run out of Comiskey Park, the Tribune reported.

Nicholson’s prodigious homer was the first of three he hit that day. He had another against Drabowsky an inning later, and hit one in the second game against Aurelio Monteagudo. Boxscore and Boxscore

Two months later at Kansas City, in his first plate appearance against Drabowsky since hitting the home runs against him, Nicholson was struck in the forehead, just above the left eye, by a fastball. He fell to the ground, bleeding. Teammates carried him off the field on a stretcher. Nicholson was taken to a hospital and needed stitches to close the wound.

“The beaning was clearly an accident,” the Kansas City Times reported. “It appeared Nicholson was hit by a fastball that took off. Drabowsky was not warned by the plate umpire, Joe Paparella, and there was nothing said to him by the White Sox players.”

Paparella told The Sporting News, “It was an inside pitch that sailed.” Boxscore

Hit or miss

As Nicholson’s strikeout rate increased, his playing time decreased with the White Sox in 1964 and again in 1965. His totals in three seasons with them: 176 hits (37 for home runs) and 341 whiffs.

One person who didn’t lose faith in Nicholson was Paul Richards, who had become general manager of the Astros. He traded for Nicholson in December 1965.

Going to a National League team meant Nicholson would get to play in his hometown for the first time as a big-leaguer. On May 30, 1966, in his first at-bat in his first game in St. Louis, Nicholson singled against Bob Gibson. Boxscore

On July 5, 1966, Nicholson hit two home runs against the Braves’ Denny Lemaster. One of the shots reached the purple seats in the fourth level of the Astrodome, 512 feet from home plate. Boxscore A month later, Nicholson belted a home run against Sandy Koufax. Boxscore

The long balls were thrilling; the strikeouts, not so much. Nicholson had the most strikeouts among Astros batters in 1966. After the season, he went to the Florida Instructional League, tried converting into a pitcher and “showed some promise,” The Sporting News reported.

Then, Paul Richards came back into his life. Richards, who left the Astros to become general manager of the Braves, acquired Nicholson in the trade that sent Eddie Mathews to Houston in December 1966.

Richards had hopes Nicholson, 27, still could be a consistent hitter, but he wanted him to begin the 1967 season in the minors at Class AAA Richmond, where he could play every day. The Braves sent hitting instructor Dixie Walker to Richmond to work with Nicholson, but the plan unraveled.

Nicholson struck out 100 times in 254 at-bats and was demoted in July 1967 to Class AA Austin (managed by Hub Kittle).

In September, Richards did Nicholson a favor and brought him to the Braves. He played his last 10 games in the majors that month. His last hit, a single, came against Bob Gibson in Atlanta. Boxscore

Nicholson’s last big-league game was Oct. 1, 1967, against the Cardinals. Naturally, his last at-bat, against Nelson Briles, resulted in a strikeout. Boxscore

That year, Mejias (of Cuba), Clemente (Puerto Rico) and Felipe Montemayor (Mexico) formed the first all-Latino starting outfield in the majors.

That year, Mejias (of Cuba), Clemente (Puerto Rico) and Felipe Montemayor (Mexico) formed the first all-Latino starting outfield in the majors. So, when Spahn returned to Milwaukee for the first time as a member of the Mets, the fans there came out to cheer for him and against the Braves.

So, when Spahn returned to Milwaukee for the first time as a member of the Mets, the fans there came out to cheer for him and against the Braves.

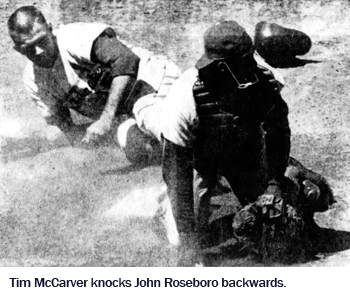

As a standout high school athlete in Memphis, McCarver

As a standout high school athlete in Memphis, McCarver  On Nov. 20, 1983, Coryell brought the San Diego Chargers to Busch Stadium to play the Cardinals.

On Nov. 20, 1983, Coryell brought the San Diego Chargers to Busch Stadium to play the Cardinals.