(Updated June 12, 2023)

John Roseboro of the Dodgers and Tim McCarver of the Cardinals were opposing catchers with similar styles. Both were former football players who viewed baseball as a contact sport.

As a standout high school athlete in Memphis, McCarver had football scholarship offers from the likes of Alabama and Notre Dame. Roseboro played football at Central State, a historically black college, in Ohio.

As a standout high school athlete in Memphis, McCarver had football scholarship offers from the likes of Alabama and Notre Dame. Roseboro played football at Central State, a historically black college, in Ohio.

According to the Los Angeles Times, Roseboro was “generally recognized as the toughest plate blocker” in baseball. When he and McCarver collided one day at the plate, the force was unlike any they’d experienced on a baseball field.

Matter of pride

The Dodgers came to St. Louis in June 1963 for a three-game weekend series with the first-place Cardinals. A sweep could vault the Dodgers from 2.5 games behind into the lead.

In the June 21 opener, Sandy Koufax was on the verge of pitching his third consecutive shutout when McCarver, batting with two outs in the ninth, slammed a three-run home run onto the pavilion roof in right. A left-handed batter, it was McCarver’s first big-league home run against a left-handed pitcher.

The Dodgers escaped with a 5-3 victory. Boxscore

Full impact

The next day’s pitching matchup on June 22 featured rookie left-hander Nick Willhite for the Dodgers against Bob Gibson. In his Dodgers debut six days earlier, Willhite shut out the Cubs. Gibson was riding a streak of four wins in a row.

With the score tied at 1-1 in the fifth inning, McCarver was on third, one out, when Curt Flood tapped the ball toward third baseman Maury Wills. McCarver broke for the plate, but Wills got to the ball and tossed it to Roseboro. “I foolishly tried to score against him,” McCarver recalled in his autobiography, “Oh, Baby, I Love It.”

Roseboro, mentored by Roy Campanella, “was the best in baseball at blocking the plate,” pitcher Johnny Klippstein said in the book “We Played the Game.” “He was tough.”

McCarver knew that, too. In his autobiography, he said Roseboro “was as intransigent at home plate as a derrick.”

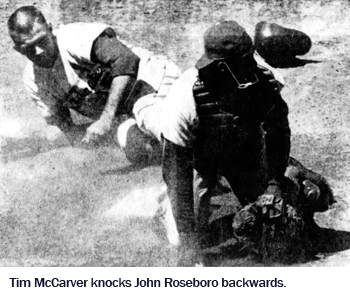

Favoring what The Sporting News described as a “rock-’em, sock-’em type of play,” McCarver gave no thought to turning back. As Roseboro protected the plate, bracing for a collision, McCarver barreled into him.

“He stood his ground, as always, his knee digging into me,” McCarver recalled in his book, “and the whole right side of my face opened up like a can of tomatoes. I had a long burn along one side of my face and he knocked my neck into a stiff state.”

According to the Los Angeles Times, McCarver came out of the crash with “a shiner, the size of a dollar.”

Roseboro lost a lens from his eyeglasses, but held onto the ball and tagged out McCarver. The impact “jammed Roseboro’s shoulder, hurt his knee and spiked his left ankle,” the Times reported. Roseboro told the newspaper it was the hardest he’d ever been hit _ “and I’ve got the bruises to prove it.”

In his 1987 book, McCarver said, “I still suffer from nerve damage in my neck, more than 20 years after that Roseboro collision. (Dodgers coach) Leo Durocher said it was the worst collision he’d ever seen.”

Another jolt

Both Roseboro and McCarver stayed in the game. Charlie James broke the tie with a solo home run for the Cardinals in the sixth.

In the seventh, McCarver batted for the first time since the collision at the plate. In his 1998 book, “Baseball for Brain Surgeons and Other Fans,” McCraver recalled, “Roseboro says through his mask, ‘Are you all right?’ “

McCarver replied, “Yeah, I’m fine. Are you?”

Roseboro said, “Oh, fine.”

After a pause, McCarver said that Roseboro, referring to the collision, told him, “That’s the way you’ve got to do it, you know.”

Like McCarver, Roseboro batted left-handed. With left-hander Bobby Shantz pitching in the ninth, Dodgers manager Walter Alston sent Doug Camilli to bat for Roseboro. Camilli singled, but the Cardinals held on for a 2-1 triumph, evening the series. Boxscore

Though the Cardinals started a right-hander, Ernie Broglio, in the series finale, Alston gave Roseboro the day off. McCarver was in the Cardinals’ lineup and tripled, but the Dodgers prevailed, 4-3. Boxscore

Roseboro didn’t start a game for more than a week because of the damage caused by the crash with McCarver.

The day after the Dodgers left town, the Giants began a series at St. Louis. In the June 24 opener, after leadoff batter Harvey Kuenn tripled, Chuck Hiller grounded to second. When Kueen broke for home, Julian Javier threw to McCarver.

“As I took the throw, I looked to my left, and Kuenn’s belt buckle was about two inches from my face,” McCarver said in his book.

Kuenn crashed into McCarver, then reached over him, trying to touch the plate, but McCarver held him off and made the putout. Boxscore

“I believed in denying the runner the plate on bang-bang, very close plays,” McCarver said in his autobiography. “That was the way I was taught, and I continued to think that’s what I was being paid to do.”

Playing to win

The Dodgers and Cardinals turned out to be the two best teams in the National League in 1963. The Dodgers took control of the pennant race in late September when they swept a three-game series in St. Louis. They also swept the Yankees in the World Series. The Cardinals, with 93 wins, placed second to the 1963 Dodgers. They won the pennant with the same number of wins in 1964.

Roseboro and McCarver were the catchers for the National League champions in seven of the 10 World Series played between 1959 and 1968, the last year the best team in the league automatically went to the World Series.

Roseboro started in all 21 games the Dodgers played in four World Series in that stretch (six in 1959, four in 1963, seven in 1965 and four in 1966). McCarver also started in all 21 games the Cardinals played in three World Series during that period (seven apiece in 1964, 1967 and 1968).

On Nov. 20, 1983, Coryell brought the San Diego Chargers to Busch Stadium to play the Cardinals.

On Nov. 20, 1983, Coryell brought the San Diego Chargers to Busch Stadium to play the Cardinals. When he was elected to the Pro Football Hall of Fame on Feb. 9, 2023, Coryell correctly was hailed as an innovator whose offenses with the Cardinals, and later the San Diego Chargers, were thrilling to watch and nerve-wracking to defend.

When he was elected to the Pro Football Hall of Fame on Feb. 9, 2023, Coryell correctly was hailed as an innovator whose offenses with the Cardinals, and later the San Diego Chargers, were thrilling to watch and nerve-wracking to defend. On Feb. 8, 1933, the Cardinals acquired pitcher Dazzy Vance and shortstop Gordon Slade from the Dodgers for pitcher Ownie Carroll and infielder Jake Flowers.

On Feb. 8, 1933, the Cardinals acquired pitcher Dazzy Vance and shortstop Gordon Slade from the Dodgers for pitcher Ownie Carroll and infielder Jake Flowers. In February 2003, the Cardinals signed Palmeiro, a free agent, to fill the same role he’d performed so well for the Angels. A left-handed contact hitter, Palmeiro was a reliable reserve outfielder whose team-oriented approach contributed to the Angels in 2002 becoming World Series champions for the first and only time since the franchise started in 1961.

In February 2003, the Cardinals signed Palmeiro, a free agent, to fill the same role he’d performed so well for the Angels. A left-handed contact hitter, Palmeiro was a reliable reserve outfielder whose team-oriented approach contributed to the Angels in 2002 becoming World Series champions for the first and only time since the franchise started in 1961. In 1954, the Cardinals had their first black player, first baseman

In 1954, the Cardinals had their first black player, first baseman