Given the chance to revive a playing career that appeared finished, Orlando Cepeda took advantage of a gimmick adopted by the American League and added to his Hall of Fame credentials with a productive season for the Red Sox.

On Jan. 18, 1973, Cepeda, 35, became the first big-league player acquired to be a designated hitter. The Red Sox signed him one week after club owners voted to allow the American League to use a designated hitter on an experimental basis for the next three seasons.

On Jan. 18, 1973, Cepeda, 35, became the first big-league player acquired to be a designated hitter. The Red Sox signed him one week after club owners voted to allow the American League to use a designated hitter on an experimental basis for the next three seasons.

A free agent released a month earlier by the Athletics, Cepeda had bad knees that prevented him from playing first base regularly, but did not restrict his hitting.

Wounded knees

The right knee was the first to give Cepeda trouble. He had surgery on the knee in December 1964 and missed most of the 1965 season with the Giants. In May 1966, he was traded to the Cardinals for Ray Sadecki.

Before the knee damage, Cepeda had been a dominant run producer with the Giants. He won the National League Rookie of the Year Award in 1958, led the league in home runs (46) and RBI (142) in 1961, and contributed 35 home runs and 114 RBI for the pennant-winning Giants in 1962.

Rejuvenated with the Cardinals, Cepeda powered them to a World Series title in 1967 and was named the recipient of the National League Most Valuable Player Award. He helped them repeat as league champions in 1968 before he was traded to the Braves for Joe Torre.

Cepeda delivered for the Braves, too, including 34 home runs and 111 RBI in 1970, until the good knee, the left one, gave out in 1971. He had left knee surgery in September 1971, got traded to the Athletics for Denny McLain in June 1972 and had another operation on the left knee soon after.

Athletics owner Charlie Finley said the surgeon, Dr. Henry Walker, told him that all of the cartilage in Cepeda’s left knee was gone, that it was almost bone on top of bone, The Sporting News reported.

In his autobiography, “Baby Bull,” Cepeda said when the Athletics released him, “I was finished as a major-league player. My legs were shot.”

Opportunity knocks

At home in Puerto Rico in January 1973, Cepeda said he wasn’t aware the American League had gotten approval that month for its teams to substitute a designated hitter for a pitcher in the batting order. He could hardly believe his good fortunate when teams began to inquire about playing in 1973.

The Red Sox were the first to make him an offer ($90,000 and a new car, according to the Boston Globe), and he accepted. Cepeda, who said he’d been a Ted Williams fan as a kid, was joining a Red Sox lineup with three other future Hall of Famers _ Luis Aparicio, Carlton Fisk and Carl Yastrzemski _ plus the likes of Tommy Harper, Rico Petrocelli and Reggie Smith.

Skeptics wondered how much help Cepeda could provide on scarred knees.

“Cepeda may have to be wheeled up to the plate in a jinrikisha, helped out of it and pushed into the batter’s box,” Clif Keane wrote in the Boston Globe.

Noting that Cepeda’s left knee “looks like a road map of Colorado,” columnist Ray Fitzgerald declared, “Maybe the American League executives could meet once more and allow the designated hitters to go to first on a motorcycle.”

Others recalled that Cepeda batted .103 against the Red Sox in the 1967 World Series and was 1-for-17 with no RBI in the four games at Boston. A right-handed batter, Cepeda said the short distance from the plate to the Green Monster wall in left at Fenway Park made him “fence happy” during that World Series.

“Everybody told me how easy it would be to hit the ball over there, and that’s what I tried to do,” Cepeda recalled to the Globe. “I got all mixed up.”

“I’ll get over that,” he promised.

Great expectations

At spring training with the 1973 Red Sox, Cepeda “has been doing a lot of limping but he also has been doing a lot of hitting,” The Sporting News reported.

Trainer Buddy LeRoux told the Globe that Cepeda had “the knees of a 55-year-old man.”

In picking the Red Sox to finish first in the American League East, The Sporting News suggested that Cepeda, “who can’t run but still can hit,” could give Boston the edge.

The first American League game of the 1973 season was Yankees versus Red Sox on April 6 at Boston. In the top of the first, the Yankees’ Ron Blomberg became the first designated hitter to make a plate appearance in a big-league game, drawing a walk from Luis Tiant with the bases loaded. The Red Sox totaled 15 runs and 20 hits in the game, but Cepeda went hitless in six at-bats. Boxscore

The next day, the Red Sox had 13 hits, none by Cepeda. Though he contributed two sacrifice flies, there already were concerns that the player designated as a hitter had thus far failed to get a hit. Boxscore

Feelin’ all right

Those concerns turned into boos in the series finale when Cepeda went hitless in his first three at-bats.

When Cepeda led off the bottom of the ninth, with the score tied at 3-3, “there was a genuine doubt about whether he should be allowed to hit,” Leigh Montville wrote in the Globe.

Pitching for the Yankees was their closer, Sparky Lyle, making his first appearance at Fenway Park since being traded by the Red Sox the year before.

With the count 1-and-1, Lyle tried to throw an inside fastball, but it caught the middle of the plate. Connecting with his 41-ounce bat, the heaviest in the majors, Cepeda’s rising liner soared over the wall in left for a walkoff home run.

“He didn’t cheat himself with the swing he took,” Lyle said to the Globe. “The wind from the swing almost knocked me over flat on my back.”

Leigh Montville described the scene as the ball carried toward the Green Monster: “Cepeda watched it, helping it clear the 37-foot wall with his entire heart, and then he broke into a trot. He came around third base and he came down the line, and when he hit the plate, he gave it a gentle Arthur Murray tap.”

“I’m Cha-Cha,” Cepeda said. “That’s my name.” Boxscore

It was Cepeda’s first walkoff home run since Sept. 30, 1965, versus Joe Nuxhall of the Reds. Boxscore

Big bopper

“It is quite likely if Cepeda hadn’t drilled Sparky’s pitch, he might have lost his designated hitter’s job to Ben Oglivie,” Clif Keane reported in the Globe.

Red Sox manager Eddie Kasko admitted, “I was looking to see better signs” from Cepeda when he came to bat against Lyle.

From then on, Cepeda had a lock on the designated hitter job. Among his highlights:

_ Two home runs and four RBI against the Indians on April 21. “Who cares whether the man can run or not?” Kasko said to the Globe. “We got him to drive in runs. He is doing that better than anyone on the club.” Boxscore

_ A grand slam, the ninth of his career, against the Rangers’ Pete Broberg on May 2. “He’s the best (DH) in the league,” Rangers manager Whitey Herzog told the Globe. Boxscore

_ A two-run home run versus Nolan Ryan in a 2-1 win over the Angels on May 29. Boxscore

_ A tie-breaking homer and the game-winning RBI in a rematch against Ryan on June 12. Boxscore

_ Four doubles and six RBI against the Royals on Aug. 8. “It’s too bad Cepeda doesn’t have a bat to match his bad legs,” Royals manager Jack McKeon said to the Globe. Boxscore

_ Five hits and four runs scored against the Angels on Aug. 12. “The most satisfying year of my career,” Cepeda told the Globe. Boxscore

One and done

Used exclusively as a designated hitter, Cepeda batted .289 with 20 home runs and 89 RBI for the second-place Red Sox. He tied Yastrzemski for the team lead in doubles (25) and was second on the club in total bases (244). He was the first recipient of baseball’s Designated Hitter of the Year Award (renamed the Edgar Martinez Award).

“Considering where my career was and the high level of competition, the designated hitter award in 1973 remains among my most meaningful baseball achievements,” Cepeda said in his autobiography. “I was back on top.”

The good vibes didn’t last long. Darrell Johnson, who replaced Kasko as manager, preferred Tommy Harper and Cecil Cooper for the designated hitter role. Cepeda was released in March 1974.

He went to Mexico, played in 28 games for a Yucatan team managed by former Cardinals teammate Julian Javier and batted .213. Back in the majors with the Royals in August 1974, Cepeda hit .215 with one home run in 33 games, ending his playing career.

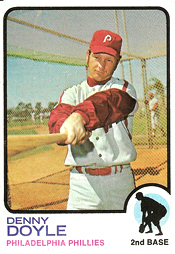

Standing 5 feet 9, he swung a 32-ounce stick _ “Dick Allen cleans his teeth with bats like that,” Doyle told Stan Hochman of the Philadelphia Daily News _ but he clobbered the Cardinals and, most improbably, their ace, Bob Gibson.

Standing 5 feet 9, he swung a 32-ounce stick _ “Dick Allen cleans his teeth with bats like that,” Doyle told Stan Hochman of the Philadelphia Daily News _ but he clobbered the Cardinals and, most improbably, their ace, Bob Gibson. A 6-foot-7 power forward and relentless rebounder, Silas debuted in the NBA with the St. Louis Hawks in 1964. His first regular-season appearance with them came two days after Gibson pitched the Cardinals to victory in Game 7 of the 1964 World Series.

A 6-foot-7 power forward and relentless rebounder, Silas debuted in the NBA with the St. Louis Hawks in 1964. His first regular-season appearance with them came two days after Gibson pitched the Cardinals to victory in Game 7 of the 1964 World Series. On Dec. 17, 1932, the Cardinals traded their future Hall of Fame first baseman, Jim Bottomley, to the Reds for pitcher Ownie Carroll and outfielder Estel Crabtree.

On Dec. 17, 1932, the Cardinals traded their future Hall of Fame first baseman, Jim Bottomley, to the Reds for pitcher Ownie Carroll and outfielder Estel Crabtree.

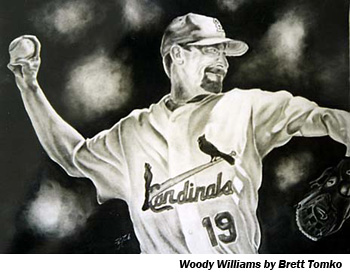

On Dec. 15, 2002, the Cardinals got Tomko from the Padres for reliever Luther Hackman and a player to be named (pitcher Mike Wodnicki).

On Dec. 15, 2002, the Cardinals got Tomko from the Padres for reliever Luther Hackman and a player to be named (pitcher Mike Wodnicki).