After following in the footsteps of Bob Gibson on the basketball court at Creighton University, Paul Silas launched his NBA career in the city where Gibson was pitching the Cardinals to championships.

A 6-foot-7 power forward and relentless rebounder, Silas debuted in the NBA with the St. Louis Hawks in 1964. His first regular-season appearance with them came two days after Gibson pitched the Cardinals to victory in Game 7 of the 1964 World Series.

A 6-foot-7 power forward and relentless rebounder, Silas debuted in the NBA with the St. Louis Hawks in 1964. His first regular-season appearance with them came two days after Gibson pitched the Cardinals to victory in Game 7 of the 1964 World Series.

During the time Silas played for the St. Louis Hawks (1964-68), Gibson pitched the Cardinals to two more National League pennants (1967-68) and another World Series title (1967).

Silas went on to play in the NBA until 1980, including for three championship teams, and then was a head coach in the league for 12 seasons.

On the rebound

When Silas was 8, he moved with his family from Arkansas to Oakland, where he grew up watching Bill Russell play basketball on the playgrounds and for McClymonds High School. Silas later attended the same school and paced the varsity basketball team to a 68-0 record in three seasons, according to the New York Times.

Residing in Oakland connected Silas with his first cousins, who formed the popular singing group, The Pointer Sisters.

Silas accepted a basketball scholarship to Creighton, the Omaha school where Bob Gibson averaged 20.2 points and 8.5 rebounds per game in three varsity seasons (1954-57).

Gibson, who began his pro baseball career in the Cardinals’ farm system in 1957, was an established Cardinals pitcher when Silas was a varsity player at Creighton (1961-64). In the winters, Gibson, 6 feet 1, would join the Creighton team in some intra-squad games.

“Gibson was tremendous,” Silas told Bob Broeg of the St. Louis Post-Dispatch. “He’d come right over to campus after a baseball season, step in to scrimmage with us, and he’d tear us up.”

Silas was pretty good, too. He averaged 20.5 points (topping Gibson’s 20.2 mark) and 21.6 rebounds per game in his three varsity seasons.

In 1964, UCLA coach John Wooden told The Sporting News, “Silas is truly one of the best players in the country. He’s both an outstanding rebounder and scorer.”

Creighton coach Red McManus said to the Omaha World-Herald, “You sort of feel that such a player comes along once in a lifetime.”

Wes Unseld, who was built similar to Silas and who would go on to have his own distinguished NBA career, was a high school player in Louisville when Silas was at Creighton. “I read a magazine article about him called ‘Chairman of the Board’ because he was such a great rebounder,” Unseld recalled to The Sporting News. “I’ve always wanted to be chairman of the board.”

Good Humor man

Being a top college player didn’t assure success in the pros. After the Hawks took Duke shooting guard Jeff Mullins in the first round of the 1964 NBA draft, the selection of Silas in the next round “was the gamble,” the Post-Dispatch reported.

“Paul weighed 250 pounds, blubber all over, and he was a horrendous shooter,” Hawks general manager Marty Blake told The Sporting News, “but, despite his weight, he was a good rebounder, got the ball out quickly and ran pretty good.”

Silas said to the Post-Dispatch, “I weighed 251 when I reported for the Hawks’ rookie camp. I had been close to that ever since I spent the summer of 1962 working in an ice cream factory. They didn’t mind us taking ice cream breaks, or carrying a quart or two home with us. I gained 40 pounds in three months.”

Below a headline “Silas To Be Corner Man If He’s Not Too Round,” the Post-Dispatch reported the rookie was the Hawks’ “chief hope of strengthening a front line that is sorely in need of strong, young replacements.”

“He’s one of the best defensive big men coming out of school,” Hawks coach Harry Gallatin told the newspaper.

In his first game, against the Cincinnati Royals, Silas totaled nine points and 13 rebounds in 24 minutes. Boxscore

For the season, playing as a backup to front-line starters Bill Bridges, Zelmo Beaty and Bob Pettit, Silas averaged 4.6 points and 7.3 rebounds per game. “Pro ball is quite a change from the college game,” Silas told the Post-Dispatch. “To me, the biggest difference is the way you must always be advancing toward the basket _ no standing around while the play develops as in college.”

Shaping up

After his rookie season, Silas went to Fort Jackson in South Carolina to serve a six-month military stint. On Aug. 14, 1965, Silas was a bystander when another soldier got into an argument with a gas station operator about a faulty repair of a car clutch, the Post-Dispatch reported. The gas station man said he felt threatened by the soldier and fired a shotgun toward the ground, according to the sheriff’s office at Columbia, S.C. Pellets struck Silas in the left foot and he required a skin graft, delaying the start to his second NBA season.

Silas primarily played a reserve role with the Hawks his first three years. Urged to lose weight, he dropped 30 pounds, reporting to training camp at 220 in 1967, and worked to develop an outside shot.

“Paul got himself ready to play first-class basketball, not only weight-wise, but mentally,” Hawks coach Richie Guerin said to the Post-Dispatch. “He’s one of the best all-round corner men in the league now.”

Pairing with Bill Bridges as the Hawks’ starting forwards, Silas had a breakthrough season in 1967-68, averaging 13.4 points and 11.7 rebounds per game.

The Hawks moved to Atlanta after the season. Silas also went on to play for the Phoenix Suns, Boston Celtics, Denver Nuggets and Seattle SuperSonics, totaling 16 seasons as a NBA player. He played for three NBA champions _ 1974 Celtics, 1976 Celtics and 1979 SuperSonics. The latter was coached by his former Hawks teammate, Lenny Wilkens.

Silas averaged more than 11 rebounds per game for seven straight seasons (1970-76). To position himself for rebounds, Silas “studied the arc and spin of his teammates’ shots to compensate for his lack of vertical skills,” the New York Times reported.

“Once he was in position, you just couldn’t move him,” Wilkens told the newspaper.

In describing his approach to rebounding, Silas said to the Post-Dispatch, “Position and timing are important. You’ve got to really want the ball. It’s attitude, desire.”

Coaching career

In 1981, Silas turned down an offer to become Creighton’s head coach, the Omaha World-Herald reported. Instead, another former standout NBA rebounder, Willis Reed, formerly of the New York Knicks, replaced Tom Apke at Creighton.

Silas preferred coaching in the NBA. He was a head coach for 12 seasons in San Diego, Charlotte, New Orleans and Cleveland. He was the first NBA head coach of 18-year-old LeBron James of the Cavaliers. “I loved Paul Silas a lot,” James told the New York Times. “He gave me a chance to showcase my talent early.”

Silas’ top season as a head coach was in 1999-2000 when he led the Charlotte Hornets to a 49-33 mark. In 2020, Silas’ son, Stephen Silas, became head coach of the NBA Houston Rockets.

On Dec. 17, 1932, the Cardinals traded their future Hall of Fame first baseman, Jim Bottomley, to the Reds for pitcher Ownie Carroll and outfielder Estel Crabtree.

On Dec. 17, 1932, the Cardinals traded their future Hall of Fame first baseman, Jim Bottomley, to the Reds for pitcher Ownie Carroll and outfielder Estel Crabtree.

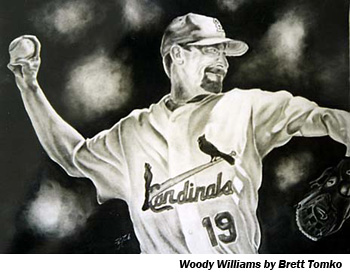

On Dec. 15, 2002, the Cardinals got Tomko from the Padres for reliever Luther Hackman and a player to be named (pitcher Mike Wodnicki).

On Dec. 15, 2002, the Cardinals got Tomko from the Padres for reliever Luther Hackman and a player to be named (pitcher Mike Wodnicki).

A left-handed power hitter, McGriff grew up in Tampa, four blocks from Al Lopez Field, spring training home of the Reds, and sold soft drinks at Tampa Stadium during NFL Buccaneers games as a youth.

A left-handed power hitter, McGriff grew up in Tampa, four blocks from Al Lopez Field, spring training home of the Reds, and sold soft drinks at Tampa Stadium during NFL Buccaneers games as a youth. In four starts against the Cardinals in 1966, Perry was 4-0 and didn’t walk a batter.

In four starts against the Cardinals in 1966, Perry was 4-0 and didn’t walk a batter.