Nimble footwork in the field and on the bases helped make shortstop Charlie Gelbert a prominent part of Cardinals championship clubs, yet it was a stumble that nearly cost him his foot and his playing career.

On Nov. 16, 1932, during a hunting trip in Pennsylvania, Gelbert accidently shot himself just above his left ankle when he tripped over a vine in the underbrush.

On Nov. 16, 1932, during a hunting trip in Pennsylvania, Gelbert accidently shot himself just above his left ankle when he tripped over a vine in the underbrush.

Gelbert underwent multiple operations and was unable to play baseball the next two years. Undaunted, he defied the odds and returned to the Cardinals in 1935.

Three years later, in 1938, White Sox pitcher Monty Stratton accidently shot himself, resulting in the amputation of his right leg above the knee. Stratton’s determined effort to pitch professionally again inspired a Hollywood movie with Jimmy Stewart in the lead role.

No film was made about Charlie Gelbert, but his comeback was just as amazing.

Name game

When Charlie Gelbert was born in Scranton, Pa., he was christened Magnus Ott Gelbert. “Magnus and Ott were the family names of my father’s grandparents in Germany,” Gelbert later told The Sporting News.

The father, Charles, a veterinarian, had been an all-America football player at the University of Pennsylvania in the 1890s. An offensive guard and defensive lineman who was 5 feet 9 and 170 pounds, Charles “was called The Miracle Man because he did so much with so little,” according to the National Football Foundation.

From as early as he could remember, Magnus Ott Gelbert disliked his name. “The boys hung all sorts of nicknames on me,” he recalled to The Sporting News. “Maggie, of course, was one of them. So I had the name changed.”

When he was 8, Magnus Ott Gelbert became Charles Magnus Gelbert, but everyone called him Charlie.

On the rise

Like his father, Charlie Gelbert became a standout athlete, but his best sport was baseball. While excelling at Lebanon Valley College in Annville, Pa., Gelbert was signed by Cardinals scout Pop Kelchner.

After three years in the minors, Gelbert got to the Cardinals in 1929 and became their shortstop. He helped them to consecutive National League pennants in 1930 and 1931 and a World Series championship.

A right-handed batter, Gelbert hit .304 during the 1930 regular season and .353 in the World Series. He followed with a .289 batting average in 1931. His squeeze bunt in Game 2 of the 1931 World Series scored Pepper Martin from third base with an insurance run. Boxscore

In 13 World Series games for the Cardinals, Gelbert played 113 innings at shortstop without making an error.

“I consider Gelbert one of the most brilliant shortstops in the game,” Cardinals owner Sam Breadon told the St. Louis Star-Times.

St. Louis columnist Sid Keener wrote, “He could hit, field, run and throw. He handled difficult grounders with ease. His throws from deep field were straight to the mark. He was an artist in playing a slow hopper in back of the pitcher.”

As a hitter, Keener noted, “He’d stretch singles into doubles and doubles into triples by daring running.”

Shotgun blast

About a week before Thanksgiving Day in 1932, Gelbert and four companions went hunting in the mountains near McConnellsburg, Pa., about 25 miles from the Maryland state line.

When Gelbert tripped on a vine, he lost his balance and fell backward, sending his feet into the air. As he crashed down heavily, the butt of his shotgun struck the ground and the weapon discharged. The load of pellets struck him in the left leg, about two inches above the ankle, and “left a ragged wound,” according to the Chambersburg (Pa.) Public Opinion newspaper.

“I thought my foot had been severed,” Gelbert told the St. Louis Star-Times. “Blood was streaming from my foot.”

According to the St. Louis Post-Dispatch, “At its deepest point, the wound severed muscles, nerves and blood vessels.” Part of his fibula bone also was shattered.

Responding to Gelbert’s shrieks, his hunting companions rushed to his aid and applied a tourniquet. Gelbert “was carried about a half mile before he could be placed” in a car of one of the hunters, the Chambersburg newspaper reported.

Gelbert was driven about 25 miles to the Chambersburg hospital. After five days there, he was transferred to a hospital in Philadelphia.

At some point, gangrene set in and doctors advised amputating Gelbert’s left foot. “I knew what that meant,” Gelbert, 26, told the Star-Times. “I’d be through as a ballplayer. I pleaded with my doctors to give me the last chance” to save the foot.

Gradually, the infection started to clear and amputation wasn’t necessary, the Star-Times reported, but he faced a long recovery.

“I never thought he’d play ball again,” Cardinals second baseman Frankie Frisch told the New York Times.

Moving forward

Teammate Sparky Adams, whose winter residence was about two hours from Philadelphia, visited Gelbert in the hospital several times, and most of the Cardinals sent him cards and letters, the Post-Dispatch reported.

A couple of days before Christmas, five Philadelphia Athletics (coach Eddie Collins, and players Jimmie Foxx, Jimmy Dykes, Lew Krausse Sr and Jim Peterson) came to his hospital room and brought presents. Gelbert and the Cardinals had opposed the Athletics in both the 1930 and 1931 World Series.

To replace Gelbert, the Cardinals made a trade for Dodgers shortstop Gordon Slade. The Cardinals’ Rogers Hornsby described Slade to columnist Sid Keener as “a brilliant player _ defensively, I mean. The team is strong enough in batting to carry a light-hitting shortstop.”

Slade started at shortstop on Opening Day for the 1933 Cardinals, but soon after was sent to the minors. In May, the Cardinals got a capable replacement, acquiring Leo Durocher from the Reds.

Durocher led National League shortstops in fielding percentage in 1933, and helped the 1934 Gashouse Gang Cardinals become World Series champions.

Gelbert received no salary from the Cardinals while sidelined in 1933 and 1934, the Star-Times reported. Cardinals players voted him a World Series share of $1,000 in 1934 _ a goodwill gesture Gelbert was grateful for in the Great Depression era. “It was Frisch who guided the players to make the generous action,” the Post-Dispatch reported. “He told the players, ‘Be big and the baseball world will accept you as big. Be cheap and the world will jeer and get you down.’ “

Remarkable return

In 1935, doctors gave Gelbert the green light to return to baseball, and he headed to the Cardinals’ training camp in Bradenton, Fla., hoping to earn a spot on the Opening Day roster of the reigning World Series champions.

“His presence in training camp was believed to be just a sympathetic gesture by the Cardinals’ officials,” the Post-Dispatch reported. “That he would ever again be deemed fit to become a cog for a pennant outfit was not dreamed of.”

As the St. Louis Globe-Democrat noted, “For two years he scarcely put the weight of his body on the shattered left leg.”

Gelbert, 29, had a shaky start to his comeback, then began making slow, steady progress. Frisch, the Cardinals’ player-manager, was patient and allowed Gelbert to ease back in. He gave Gelbert a spot on the Opening Day roster as a backup to Durocher at short and to Pepper Martin at third base.

One week into the season, Gelbert appeared in a game, running for catcher Bill DeLancey. Boxscore

A month later, on May 21, 1935, Gelbert got to bat. Boxscore

Gilbert’s first hit in his comeback year was a single against former teammate Tex Carleton of the Cubs on June 2. Boxscore

A week later, Frisch put Gelbert in the starting lineup for the slumping Durocher, who was batting .215.

On June 9, in a game versus the Cubs, Gelbert had four hits, including a home run against Charlie Root, drove in three runs and scored twice. Boxscore

Gelbert made 12 starts at shortstop for the Cardinals in June, hit .340 for the month and continued to play after he was spiked in the left foot during a game against the Cubs.

The sight of Gelbert producing and playing through pain seemed to snap Durocher from his slump. Reinstated at shortstop, Durocher batted .290 with 22 RBI in July and hit well the rest of the season.

Position switch

Early in August, after Pepper Martin was injured, Frisch started Gelbert at third base and he made the most of the opportunity.

“He has been fielding confidently and hitting in a timely fashion,” The Sporting News reported.

Sid Keener noted in the Star-Times, “He has fielded phenomenally at the far corner, handling torrid cracks with the utmost ease, making perfect throws to first base, prancing to short left field for difficult pop twisters, and getting his share of hits in the pinch.”

Gelbert made 30 starts at third base for the 1935 Cardinals. For the season, he hit .292, including .309 with runners in scoring position. He did this even though, as Sid Keener wrote, “Whenever too much pressure is put on the left foot, Gelbert reeks with pain.”

The Cardinals opened the 1936 season with Gelbert, 30, as their third baseman, but he hit .167 in May and got benched. After batting .229 for the season, the Cardinals traded him to the Reds.

Gelbert was a utilityman with the Reds (1937), Tigers (1937), Senators (1939-40) and Red Sox (1940).

He served in the Navy for three years during World War II, mostly in the Pacific, and achieved the rank of lieutenant commander. Afterward, he became baseball coach at Lafayette College in Pennsylvania and amassed a record of 307-176.

On Nov. 6, 1972, the Cardinals traded outfielder Jorge Roque to the Expos for McCarver.

On Nov. 6, 1972, the Cardinals traded outfielder Jorge Roque to the Expos for McCarver. On April 29, 1981, Durham slugged a two-run home run versus Bruce Sutter to tie the score at Wrigley Field in Chicago.

On April 29, 1981, Durham slugged a two-run home run versus Bruce Sutter to tie the score at Wrigley Field in Chicago. Digging in against Sutter in Game 2, Durham later told the Tribune, “I was really keyed up to face him. Any time you face a guy you’ve been traded for, you really want to get a piece of him.”

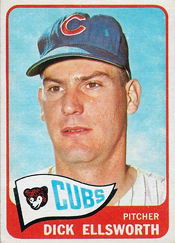

Digging in against Sutter in Game 2, Durham later told the Tribune, “I was really keyed up to face him. Any time you face a guy you’ve been traded for, you really want to get a piece of him.” A left-hander who pitched in 13 seasons with the Cubs, Phillies, Red Sox, Indians and Brewers, Ellsworth had a career record of 115-137. He twice lost 20 in a season with the Cubs (9-20 in 1962 and 8-22 in 1966).

A left-hander who pitched in 13 seasons with the Cubs, Phillies, Red Sox, Indians and Brewers, Ellsworth had a career record of 115-137. He twice lost 20 in a season with the Cubs (9-20 in 1962 and 8-22 in 1966). On Oct. 25, 1932, the Cardinals signed Hornsby for a second stint with them.

On Oct. 25, 1932, the Cardinals signed Hornsby for a second stint with them. Instead, his hopes for a storybook ending got washed away on a stormy St. Louis night.

Instead, his hopes for a storybook ending got washed away on a stormy St. Louis night.