The Cardinals acquired the player who might have helped them win a division title in 1973, but gave him away before he played a game for them.

On Oct. 26, 1972, the Cardinals got outfielder Larry Hisle from the Dodgers for pitchers Rudy Arroyo and Greg Milliken.

On Oct. 26, 1972, the Cardinals got outfielder Larry Hisle from the Dodgers for pitchers Rudy Arroyo and Greg Milliken.

Hisle might have been a fit to join a Cardinals outfield with Lou Brock and either Jose Cruz or Bake McBride.

Instead, on Nov. 29, 1972, a month after acquiring him, the Cardinals traded Hisle to the Twins for reliever Wayne Granger.

Hisle fulfilled his potential with the Twins and later with the Brewers. Granger, in his second stint with St. Louis, was a disappointment.

The 1973 Cardinals, who ranked last in the National League in home runs, finished 1.5 games behind the division champion Mets. Hisle’s 15 home runs for the 1973 Twins would have made him the team leader on the 1973 Cardinals.

Prized prospect

Born in Portsmouth, Ohio, Larry Hisle was named by his mother, a baseball fan, in honor of Larry Doby, who became the first black player in the American League, according to the Society for American Baseball Research (SABR). Hisle’s parents died when he was a youth and he was adopted by Orville and Kathleen Ferguson, “two of the finest people in the world,” Hisle told United Press International.

Hisle played youth baseball with two other future big-leaguers, Al Oliver and Gene Tenace, according to SABR, but he also was a standout prep basketball player. When Oscar Robertson, recruiting for the University of Cincinnati, called, “I almost dropped the phone,” Hisle told The Sporting News.

After agreeing to play basketball at Ohio State, Hisle was picked by the Phillies in the second round of the 1965 baseball draft and signed with them. A right-handed batter, he played two seasons at the Class A level in the minors, then reported in 1968 to Phillies spring training camp, where he roomed with Bill White.

In choosing Hisle, 20, to be the Phillies’ 1968 Opening Day center fielder, manager Gene Mauch told The Sporting News, “Hisle is the best center fielder I’ve ever had.”

The experiment didn’t last long. Though he hit .364 in 11 at-bats for the 1968 Phillies, Hisle was sent to the minors before the end of April.

Rookie season

The Phillies named Hisle their center fielder for 1969, but he had a shaky start. He hit .159 in April and removed himself from a game because of what the team physician described to The Sporting News as “acute anxiety.”

“We’re all aware he’s a very intense, high-strung young man who is going to take a little longer to adjust up here,” Phillies manager Bob Skinner said to The Sporting News.

Hisle did better in May, producing four hits, two RBI, two runs and two stolen bases in a game against the Cardinals. Boxscore

Before a game in Philadelphia, the Giants’ Willie Mays chatted with Hisle and told him, “Open your stance, take it easy and concentrate on just meeting the ball,” The Sporting News reported. Hisle responded with four hits and two RBI that day. Boxscore

Phillies teammate Dick Allen aided Hisle, too, and became a mentor. “I’ll never forget how much he helped me,” Hisle told the Philadelphia Inquirer.

Hisle hit .266 with 20 home runs and 18 stolen bases for the 1969 Phillies.

Too far, too fast

Dick Allen was traded to the Cardinals after the 1969 season in a deal involving center fielder Curt Flood, who refused to report.

With neither Allen nor Flood, the Phillies needed Hisle to step up, but he didn’t, hitting .205 in 1970 and .197 in 1971.

“I put too much pressure on myself,” Hisle said to the Chicago Sun-Times. “I doubted my ability.”

In October 1971, the Phillies dealt Hisle to the Dodgers for Tommy Hutton.

Hisle “was built up as the potential superstar who would lead the Phillies out of the wilderness, and he wasn’t ready to handle the role,” Philadelphia Inquirer columnist Frank Dolson wrote. “The enormous pressures beat him down, sent his batting average plummeting, and turned the fans who had cheered him as a rookie into a booing mob that virtually chased him out of town.”

Mind games

At spring training in 1972, Hisle was the last player cut by the Dodgers, according to the Albuquerque Journal. Rather than go to the minors, Hisle said he considered quitting baseball. He was attending Ohio University in the off-seasons, studying math and physical education, “and has thought of teaching and social work,” the Los Angeles Times reported.

A voracious reader of authors as diverse as B.F. Skinner and James Joyce, Hisle “dabbles in analytic geometry, and worries about what happened to his hitting,” the Los Angeles Times noted. “He may be, he says, too much of a thinker for his own good.”

The Dodgers assigned Hisle to Albuquerque, hoping the manager there, Tommy Lasorda, would help him overcome self-doubts.

Playing for Lasorda, “I learned that the most important thing a person can say about himself is, ‘I believe in myself,’ ” Hisle told the Philadelphia Inquirer.

Hisle hit .325 with 23 home runs and 91 RBI for Albuquerque in 1972.

The Twins tried to acquire him after the season, but the Dodgers wanted pitcher Steve Luebber in return. Luebber was rated the best pitching prospect in the Twins’ system and they didn’t want to trade him, so the Dodgers dealt Hisle, 25, to the Cardinals.

Coming and going

“Hisle could play a big part in the youth movement of the Cardinals,” the St. Louis Post-Dispatch declared.

The Cardinals brought Hisle to St. Louis and told him “they were hoping I could help the outfield defense,” Hisle told the Minneapolis Star Tribune. “From what I heard, it needed help. I was really happy to join the Cardinals.”

General manager Bing Devine also was seeking help for the bullpen, and approached the Twins about Wayne Granger, a former Cardinal. Granger’s 19 saves for the 1972 Twins were six more than Cardinals pitchers totaled that year.

“We had talked with the Twins about Granger shortly after the season ended, but they wanted a hitter in return and we didn’t have anyone available,” Devine told The Sporting News. “After we got Hisle, they expressed a strong interest in him.”

The Twins hardly could believe their good luck. Granger “had not endeared himself to the front office with charges that the Twins weren’t a first-class organization,” The Sporting News reported, and they were eager to trade him.

“It was fortunate for us that Bing Devine was interested in Wayne Granger,” Twins owner Calvin Griffith told columnist Sid Hartman. “We talked to Devine about Hisle. He was reluctant to give him up, but he wanted Granger.”

Devine said to The Sporting News, “We really had figured on Hisle as an extra man on the club because he can do so many things.”

Nothing personal

Hisle was at home when the Cardinals called, informing him of the trade to the Twins. “I was disappointed and hurt,” he told the Minneapolis Star Tribune.

According to the newspaper, “Hisle later received a handwritten note from Bing Devine. Devine apologized for the quick trade to Minnesota, explaining it was not intentional nor a snub at Hisle, but merely something which Devine felt could help the Cardinals. Hisle appreciated the letter, and still has it.”

The Twins made Hisle feel at home, naming him their center fielder. “I’m getting a chance to play regular here,” he told the Minneapolis newspaper. “I don’t know if I would have played every day for the Cardinals.”

Hisle scored 88 runs and drove in 64 for the 1973 Twins. His 230 total bases ranked third on the team, behind only Rod Carew and Tony Oliva.

Granger was 2-4 with five saves and a 4.24 ERA for the 1973 Cardinals before he was traded to the Yankees in August.

Hisle had big seasons for the Twins in 1976 (96 RBI, 31 stolen bases) and 1977 (28 home runs, 119 RBI). Granted free agency, he signed with the Brewers and had 34 home runs, 115 RBI and 96 runs scored for them in 1978.

A two-time all-star, Hisle played 14 seasons in the majors. He was the hitting coach for the World Series champion Blue Jays in 1992 and 1993.

On Oct. 17, 1962, the Cardinals acquired outfielder George Altman, pitcher

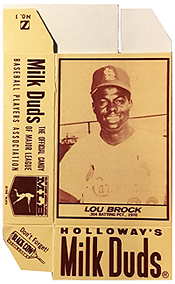

On Oct. 17, 1962, the Cardinals acquired outfielder George Altman, pitcher  In September 1972, the Federal Trade Commission banned a Milk Duds television commercial featuring Brock because it deemed the advertisement as deceptive.

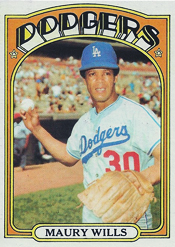

In September 1972, the Federal Trade Commission banned a Milk Duds television commercial featuring Brock because it deemed the advertisement as deceptive. In the 10-year period from 1959 to 1968, the Cardinals and Dodgers combined to win seven league pennants and five World Series titles.

In the 10-year period from 1959 to 1968, the Cardinals and Dodgers combined to win seven league pennants and five World Series titles. Musial pitched for the only time in a big-league game on Sept. 28, 1952, in the Cardinals’ season finale against the Cubs at St. Louis.

Musial pitched for the only time in a big-league game on Sept. 28, 1952, in the Cardinals’ season finale against the Cubs at St. Louis.