(Updated June 16, 2024)

After a playing career as an outfielder and first baseman in the majors during the 1960s, Lee Thomas was willing to do whatever it took to remain in the game. The Cardinals gave him a chance and he made the most of it.

Thomas served several roles with the Cardinals before becoming a top baseball executive. Having earned the respect and trust of Whitey Herzog, Thomas was responsible for developing the pipeline that supplied much talent for the Cardinals’ championship clubs in the 1980s.

Thomas served several roles with the Cardinals before becoming a top baseball executive. Having earned the respect and trust of Whitey Herzog, Thomas was responsible for developing the pipeline that supplied much talent for the Cardinals’ championship clubs in the 1980s.

Impressed by what he accomplished, the Phillies hired Thomas and he was their general manager when they won a National League title in 1993.

Settled in St. Louis

Born in Peoria, Thomas moved with his mother and stepfather, an auto mechanic, to Jacksonville, Ill., and Waco, Texas, before settling in St. Louis when he was 8, the St. Louis Post-Dispatch reported.

A standout athlete at Beaumont High School in St. Louis, Thomas, 18, hit .580 his senior baseball season and was signed by the Yankees in June 1954.

Another Yankees outfield prospect at the time was Whitey Herzog.

A left-handed batter who hit for power and average, Thomas spent seven seasons in the Yankees’ farm system before reaching the majors with them in 1961.

A special opportunity occurred for Thomas when the Yankees played the Cardinals at St. Louis in a pair of exhibition games on the eve of the 1961 season opener. Substituting for right fielder Roger Maris late in both games, Thomas got to play before friends and family, and singled in an at-bat against Mickey McDermott.

Two weeks later, making his big-league debut as a pinch-hitter at Baltimore, Thomas singled to center against future Hall of Famer and former Cardinal Hoyt Wilhelm. Playing right field for the Orioles was Whitey Herzog. Boxscore

In his book, “Season of Glory,” Yankees manager Ralph Houk said, “Lee hit good in the minors but he came to the Yankees at a bad time. He came along when we had (Mickey) Mantle and (Roger) Maris, and there just wasn’t a place for him.”

Fitted for a halo

In May 1961, the Yankees dealt Thomas to the Angels, a first-year expansion club. He became the first Angels player to hit a grand slam (against the Orioles’ Milt Pappas), the first to hit three home runs in a game and the first to go 5-for-5.

On Sept. 5, 1961, Thomas had 9 hits in 11 at-bats in a doubleheader against the Athletics at Kansas City. Boxscore and Boxscore

The next year, Thomas hit .290 with 26 home runs and 104 RBI for the 1962 Angels and was named an American League all-star.

Those early Angels teams were stocked with colorful characters such as veterans Steve Bilko, Rocky Bridges, Art Fowler and Ted Kluszewski, and newcomers the likes of Bo Belinsky, Dean Chance, Jim Fregosi, Bob “Buck” Rodgers and Thomas.

“We were a group of guys no one wanted and were out to prove we could play,” Thomas told the Los Angeles Times.

Rodgers, who went on to manage the Brewers, Expos and Angels, was Thomas’ road roommate with the Angels. He gave Thomas the nickname “Mad Dog” for hurling a 3-wood into a tree during a celebrity golf outing at the Rio Hondo Club.

“I can’t say anything bad about him, except I had to order the pizza all the time when we were roomies,” Rodgers said to the Los Angeles Times.

After the 1962 season, Thomas had surgery on a knee he damaged during his prep football days. He wasn’t the same after that. In his last five big-league seasons (1964-68), he played for five teams (Angels, Red Sox, Braves, Cubs, Astros).

(On the morning of May 28, 1966, the Braves dealt Thomas to the Cubs for reliever Ted Abernathy. That afternoon, Thomas made his Cubs debut and drove in the tying run with a single against Abernathy. Boxscore)

Multiple skills

Thomas made his last big-league playing appearance on Sept. 27, 1968, as a pinch-hitter for the Astros against the Cardinals at St. Louis. Boxscore

After playing for the Nankai Hawks in Japan in 1969 (a teammate was former Cardinals second baseman Don Blasingame), Thomas finished his playing career with the Cardinals’ Tulsa affiliate managed by Warren Spahn.

“I knew I wanted to stay in the game,” Thomas said to the Los Angeles Times.

Back home in St. Louis, he got hired by the Cardinals. According to the team media guide, Thomas filled the following roles:

_ 1971-72: Cardinals batting practice pitcher and bullpen coach.

_ 1973: Manager of a Cardinals team in the rookie Gulf Coast League in Sarasota, Fla.

_ 1974: Manager of the Cardinals’ Modesto farm club in the California League.

_ 1975: Cardinals administrative assistant to Joe Cunningham in sales and promotions.

“I sold season tickets,” Thomas told author Tom Wheatley. “It wasn’t easy. You had to wine and dine people to sell them … and we were horsefeathers for a while there.”

_ 1976-80: Cardinals traveling secretary.

In his autobiography, Cardinals general manager Bing Devine, who brought Thomas into the organization, said, “He did more than just make travel arrangements for the ballclub. When I had a question on player development, I always valued him as a sounding board. I liked to check with him when I wanted an opinion from someone not so close to me in the baseball office.”

_ 1981-88: Cardinals director of player development.

Whitey Herzog, who had the dual role of Cardinals manager and general manager, chose Thomas to be director of player development after the 1980 season.

“Lee is a lot like me,” Herzog told the Philadelphia Inquirer. “Lee has enough confidence in his ability to make a decision and go ahead and do it.”

During Thomas’ time as director of player development, the Cardinals developed players such as Vince Coleman, Danny Cox, Ricky Horton, Terry Pendleton, Joe Magrane, Greg Mathews, John Stuper, Andy Van Slyke and Todd Worrell. Thomas suggested the successful shifting of Pendleton from second base to third. Thomas and scout Hal Smith also initiated the conversion of Worrell from starter to closer.

In 1983, Thomas brought in his close friend and former Angels teammate, Jim Fregosi, to manage the Cardinals’ top farm team at Louisville. With Thomas and Fregosi in synch, the talent pipeline flowed.

“We respect each other’s abilities, and we have no problem about communication,” Fregosi told the Los Angeles Times.

Winning touch

The Cardinals won three National League pennants and a World Series championship during Thomas’ time as director of player development.

Herzog, who as director of player development for the Mets helped build the team that won the 1969 World Series title, said to the Los Angeles Times, “The guy in charge of player development manages six or seven clubs at the same time. He has to have a feel for every player at every level.”

As for Thomas, Herzog said, “He gave me the right answer every time I called to ask if a certain player or pitcher was ready. That’s what you want from a guy in that position.”

When Cardinals general manager Joe McDonald was ousted in January 1985, “I wanted Lee Thomas” to replace him, Herzog told the Los Angeles Times, but the Cardinals hired Dal Maxvill.

In June 1988, Thomas left the Cardinals to be general manager of the last-place Phillies. He hired Fregosi to be Phillies manager in 1991. Two years later, with Thomas and Fregosi in charge, the Phillies became National League champions.

“Big-league front offices are well-stocked with executives who have a hard time pulling the trigger,” wrote Philadelphia Inquirer columnist Frank Dolson. “They hem. They haw. They hedge. Thomas does none of the above. He shoots from the hip. In that way, he is much like his old boss, Whitey Herzog.”

Thomas told Cardinals Magazine, “I don’t think I would have ever been a general manager without working for Whitey and the success that we had. When I got to be a GM, I’d still call him.”

In 1922, Hornsby had a 33-game hitting streak for the Cardinals. It remains the franchise record.

In 1922, Hornsby had a 33-game hitting streak for the Cardinals. It remains the franchise record. In September 1982, the Cardinals clung to first place in the National League East Division by a half game, entering a series against the pursuing Phillies at Philadelphia.

In September 1982, the Cardinals clung to first place in the National League East Division by a half game, entering a series against the pursuing Phillies at Philadelphia. In September 1952, Slaughter delivered walkoff wins for the Cardinals in consecutive games versus the Pirates.

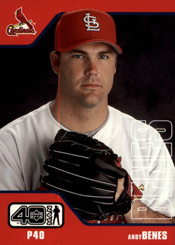

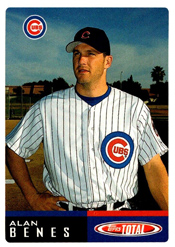

In September 1952, Slaughter delivered walkoff wins for the Cardinals in consecutive games versus the Pirates. On Sept. 6, 2002, brothers Andy Benes of the Cardinals and Alan Benes of the Cubs were the starting pitchers in a game at St. Louis. It was the first time a Cardinals starting pitcher was matched against a sibling, the St. Louis Post-Dispatch reported.

On Sept. 6, 2002, brothers Andy Benes of the Cardinals and Alan Benes of the Cubs were the starting pitchers in a game at St. Louis. It was the first time a Cardinals starting pitcher was matched against a sibling, the St. Louis Post-Dispatch reported. Two weeks later, Andy rejoined the Cardinals. In late August, the Cubs called up Alan.

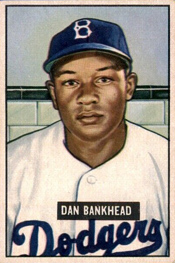

Two weeks later, Andy rejoined the Cardinals. In late August, the Cubs called up Alan. In August 1947, Bankhead debuted for the Dodgers against the Pirates. His second appearance came against the Cardinals.

In August 1947, Bankhead debuted for the Dodgers against the Pirates. His second appearance came against the Cardinals.