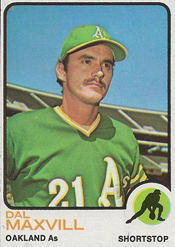

A season that began with Dal Maxvill in a batting slump, resulting in his benching, ended for him with a World Series championship.

On Aug. 30, 1972, the Cardinals traded Maxvill to the Athletics for minor-league third baseman Joe Lindsey and a player to be named (minor-league catcher Gene Dusan).

A gifted fielder, Maxvill was a winner, and he brought those qualities with him to the Athletics.

Maxvill was a member of seven World Series clubs _ five as a player (Cardinals of 1964, 1967, 1968 and Athletics of 1972 and 1974) and two as a general manager (Cardinals of 1985 and 1987). Four of those (1964 and 1967 Cardinals and 1972 and 1974 Athletics) won World Series titles.

Getting it done

A graduate of Washington University in St. Louis with a degree in electrical engineering, Maxvill signed with the Cardinals in 1960 and made his mark with them when he started at second base in all seven games of the 1964 World Series as a replacement for injured Julian Javier.

After fending off a challenge from Jerry Buchek, Maxvill became the Cardinals’ shortstop in 1966. A light hitter with little power, Maxvill earned the job because of his glove. He was their shortstop on the 1967 and 1968 World Series teams. The 1968 season was Maxvill’s best: He hit .253 and earned a Gold Glove Award.

Maxvill, 33, was the Opening Day shortstop for the Cardinals in 1972, but he went hitless in his first 21 at-bats and was replaced by Ed Crosby.

Though Crosby lacked Maxvill’s fielding skills, the Cardinals were willing to play him if he hit. After batting .324 in April, Crosby hit .217 in May and Maxvill returned to the starting lineup.

Rejuvenated, Maxvill hit .280 in June and .253 in July. To his delight, he hit for a higher average in those months than his road roommate, Joe Torre, the reigning National League batting champion, did. Torre hit .250 in June and .252 in July.

Maxvill drove in four runs against the Phillies on July 2 Boxscore and hit his last big-league home run, an inside-the-park poke against the Astros’ Larry Dierker, on July 9. Boxscore

“He’s being more aggressive at the plate,” Cardinals hitting coach Ken Boyer told The Sporting News. “He’s not taking so many good pitches.”

Cardinals manager Red Schoendienst said Maxvill also was fielding better “than any other infielder in the National League.”

The Cardinals, though, fell out of contention, and general manager Bing Devine was looking to trade for prospects.

Change of scene

With their record at 58-61, the Cardinals traded outfielder and first baseman Matty Alou to the Athletics on Aug. 27. Three days later, Maxvill was dealt.

The Maxvill trade was the fifth involving the Athletics and Cardinals in 1972. Describing Athletics owner Charlie Finley as “an aggressive guy,” Devine told The Sporting News, “He calls every day and does not seem to worry about a player’s age or salary.”

On the day they acquired Maxvill, the Athletics were in first place, a half game ahead of the White Sox, in the American League West Division.

Maxvill’s departure left Lou Brock and Bob Gibson as the only Cardinals players from the 1967 and 1968 pennant-winning teams.

“The future is more important than the present now,” Devine said to the St. Louis Post-Dispatch.

Maxvill told the newspaper he hadn’t expected to be traded but was grateful the Cardinals sent him to a contender.

Fitting in

The Athletics got Maxvill to play second base. Their shortstop, Bert Campaneris, led the American League in stolen bases for the sixth time in 1972 and he also led the league’s shortstops in putouts that season.

Dick Green, the Athletics’ Opening Day second baseman, suffered a herniated disc in April and needed back surgery. His replacement, Larry Brown, suffered the same injury in June.

Maxvill was one of 11 players used at second base by the Athletics in 1972.

In his Athletics debut, on Sept. 1 against the Tigers, Maxvill started at second and contributed two hits and a sacrifice bunt. Boxscore

Maxvill made 21 September starts at second for the 1972 Athletics, but manager Dick Williams often lifted him for a pinch-hitter early in the games. During one stretch, he made five starts without getting a plate appearance.

Key contributor

On Sept. 20, Maxvill contributed two defensive gems to help the Athletics beat the second-place White Sox and move five games ahead of them with two weeks left to play. In the clubhouse after the game, a grateful Dick Williams greeted Maxvill “with a big kiss on the cheek,” The Sporting News reported. Boxscore

“I like this ballclub,” Maxvill told the Oakland Tribune. “This is the type of ballclub we had in St. Louis five or six years ago when we won pennants.”

A week later, on Sept. 28, Maxvill drove in the winning run in the division title clincher against the Twins.

With the score tied at 7-7, Sal Bando led off the bottom of the ninth and was hit by a pitch from Dave LaRoche. Williams ordered the next batter, Maxvill, to attempt a sacrifice bunt. Squaring to bunt, Maxvill watched the first three pitches sail wide, then took a called strike.

Given the green light by Williams to swing at the 3-and-1 pitch, Maxvill drove a double into left-center, scoring Bando with the winning run and giving the Athletics the division title. Boxscore

Maxvill told the Oakland Tribune, “This was one of the most important hits I’ve ever had. The most important.”

It turned out to be his only RBI for the 1972 Athletics.

Helping hand

Dick Green was back for the American League Championship Series against the Tigers, so he started at second base and Maxvill was a reserve.

In Game 2, shortstop Bert Campaneris was ejected in the seventh inning for flinging his bat toward the mound after being hit in the ankle by a Lerrin LaGrow pitch. Video Maxvill replaced Campaneris at short. Boxscore

American League president Joe Cronin suspended Campaneris for the remainder of the series. Maxvill started at shortstop in each of the following three games and fielded flawlessly, helping the Athletics clinch their first pennant since 1931. Game 5 video clips

Baseball commissioner Bowie Kuhn allowed Campaneris to play in the 1972 World Series but extended the suspension to the first five games of the 1973 regular season.

Maxvill was on the World Series roster but didn’t appear in a game of the classic won by the Athletics against the Reds.

Because of Campaneris’ suspension, Maxvill was the Opening Day shortstop for the reigning champions in 1973. The Cardinals’ Opening Day shortstop, Ray Busse, was a bust and eventually got replaced by Mike Tyson.

In July 1973, Maxvill’s contract was purchased by the Pirates. Released in April 1974 after starting at shortstop on Opening Day for the Pirates, he was reacquired by the Athletics and helped them win another World Series title.

Maxvill played two innings in the 1974 World Series against the Dodgers. For his career, he played in 179 World Series innings (120 at shortstop and 59 at second base) and committed no errors.

Maxvill, 36, began the 1975 season as a coach on the staff of Athletics manager Al Dark. Activated in August, Maxvill contributed to their division title run.

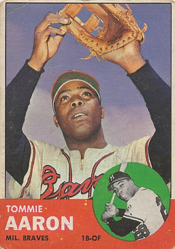

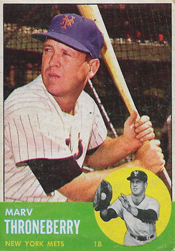

After stints as a coach with the Mets, Cardinals and Braves, Maxvill became the Cardinals’ general manager in 1985 and remained in that role until 1994.

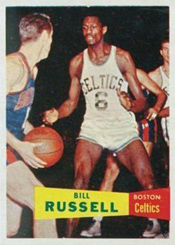

In April 1956, the Celtics traded for the rights to the Hawks’ first-round draft spot and used it to take Russell. Eight months later, when Russell made his NBA debut with the Celtics, it came in a game against the Hawks.

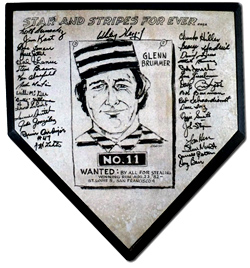

In April 1956, the Celtics traded for the rights to the Hawks’ first-round draft spot and used it to take Russell. Eight months later, when Russell made his NBA debut with the Celtics, it came in a game against the Hawks. Defining the spirit of a Cardinals club that used aggressiveness to overcome a lack of power, Glenn Brummer stole home, giving the Cardinals an improbable walkoff win in the heat of a pennant race.

Defining the spirit of a Cardinals club that used aggressiveness to overcome a lack of power, Glenn Brummer stole home, giving the Cardinals an improbable walkoff win in the heat of a pennant race.