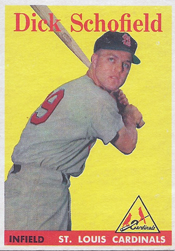

For a player labeled a utility man, Dick Schofield left a prominent mark.

He helped the Pirates, Dodgers and Cardinals win National League pennants. He played 19 seasons in the majors. He was the second of four generations in his family to play pro baseball.

He helped the Pirates, Dodgers and Cardinals win National League pennants. He played 19 seasons in the majors. He was the second of four generations in his family to play pro baseball.

An infielder who reached the majors with the Cardinals at 18, Schofield had three stints with them in three different decades.

All in the family

Dick Schofield’s father, John Schofield, played in the minor leagues for 10 seasons and was nicknamed Ducky. At home in Springfield, Ill., John taught baseball to his son. “We’d go out and he’d hit nine million ground balls to me,” Dick told author Danny Peary for the book “We Played the Game.”

When Dick was 8, his father showed him how to bat from both sides of the plate and Dick, a natural right-hander, remained a switch-hitter in the pros.

John Schofield also took Dick on trips to St. Louis to see the Red Sox play the Browns because Ted Williams was Dick’s favorite player. Dick became a Red Sox fan, he told the St. Louis Post-Dispatch.

During his senior baseball season in high school, Dick Schofield drew the interest of most big-league teams. A shortstop, he hoped to sign with the Red Sox, but the highest offers came from the Cardinals and White Sox.

Big bonus

On June 3, 1953, Schofield signed with the Cardinals, even though, as he told Danny Peary, they were a team “I had always rooted against.”

The $40,000 he received was then the largest bonus paid by the Cardinals. “He’s got a great arm,” Cardinals manager Eddie Stanky told the Post-Dispatch after seeing Schofield work out with the team. “His hands are extremely quick.”

Under the rules then, an amateur player signing for more than $6,000 was required to spend his first two seasons with the big-league team.

Schofield, 18 and looking younger, joined the Cardinals in New York. “I was scared to death,” he recalled to Peary. “The team was playing Brooklyn and I checked into the Commodore Hotel in Manhattan. Then I rode to the ballpark with Stan Musial and Red Schoendienst. They asked me to come along. Imagine that!”

Schofield was assigned to room on the road with the Cardinals’ backup catcher, Ferrell Anderson, 35. “He was like my dad and took good care of me,” Schofield told Peary. “He made it easier for me.”

Learning curve

Schofield was called Ducky by Cardinals players after they were introduced to his father and learned it had been his nickname.

He didn’t get into a game during his first month with the Cardinals, and spent his days being mentored by Stanky and shortstop Solly Hemus.

Stanky “knew baseball better than anybody I ever met,” Schofield told Peary. “Stanky and Hemus helped me learn to play shortstop in the majors, especially turning the double play.”

On June 25, in a game at St. Louis, Stanky complained that Giants pitcher Jim Hearn wasn’t coming to a stop in his delivery. After losing his argument with umpire Augie Donatelli, Stanky threw a towel from the dugout and got a warning from the ump, the Post-Dispatch reported.

Not wanting to back down, but not wanting to get ejected, Stanky turned to Schofield. Knowing the rookie wouldn’t get into the game, Stanky told him to toss a towel, according to the Society for American Baseball Research. Schofield obeyed, and Donatelli ejected him from a game before he’d ever played in one. Boxscore

Hello and goodbye

When Schofield made his big-league debut, on July 3, 1953, against the Cubs at Chicago, it was as a pinch-runner. Boxscore

His first hit came two weeks later, a single versus Johnny Podres at Brooklyn. Boxscore

Used primarily as a pinch-runner, Schofield hit .179 for the Cardinals in 1953 and .143 in 1954.

With the two mandatory seasons on the big-league club completed, Schofield spent most of the 1955 and 1956 seasons playing for manager Johnny Keane at minor-league Omaha.

(Schofield married his wife Donna in Omaha in 1956. Tyrone Power and Kim Novak, in town to promote their movie, “The Eddy Duchin Story,” sent them a cake, the Post-Dispatch reported, and that’s why the Schofields’ first child, a daughter, was named Kim.)

A backup to Cardinals shortstop Al Dark in 1957, Schofield was a reserve again in 1958 when he was traded to the Pirates in June for infielders Gene Freese and Johnny O’Brien.

“I was totally surprised,” Schofield said to Peary. “I thought the world had come to an end. Nobody wanted to play on the Pirates then. They were a last-place team and Forbes Field was a tough park.”

(According to Schofield, Freese’s reaction to the deal was: “They traded two hamburgers for a hot dog.”)

Key contribution

Schofield, strictly a shortstop with the Cardinals, also was used at second and third by Pirates manager Danny Murtaugh. With Bill Mazeroski at second and Dick Groat at short, Schofield got few starts, but grew to like the Pirates.

On Sept. 6, 1960, with the Pirates contending for a National League pennant, Groat suffered a broken left wrist when hit by a pitch from the Braves’ Lew Burdette. Schofield, hitless since May, was Murtaugh’s choice to replace Groat.

Steady on defense, Schofield surprised with the bat. He hit .375 in September and his on-base percentage for the month was .459.

“He was as fine a utility infielder that ever played this game,” Groat said to Peary. “He could give you two or three weeks of great play at any one of those positions.”

The Pirates won the pennant, but Groat was reinserted at shortstop for the World Series against the Yankees. In Game 2, a Yankees rout, Schofield entered in the sixth and got a single and a walk versus Bob Turley. Boxscore

Helping hand

Groat was traded to the Cardinals after the 1962 season and Schofield, at last, became a starting shortstop. He was the Pirates’ starter in 1963 and 1964. When rookie Gene Alley was deemed ready to take over in 1965, Schofield was dealt to the Giants in May and started for them that season.

Another rookie, Tito Fuentes, became the Giants shortstop in 1966 and Schofield was shipped to the Yankees in May.

On Sept. 10, 1966, the Dodgers acquired Schofield to help them in their pennant drive. He took over for Jim Gilliam and John Kennedy at third base, and stabilized the position, helping the Dodgers win the pennant.

According to The Pittsburgh Press, Dodgers pitcher Don Drysdale said, “He’s been making the big play for us ever since we got him. If it isn’t his glove, it’s his bat. If it isn’t his bat, it’s his base running.”

Because Schofield joined the Dodgers after Sept. 1, he wasn’t eligible to play in the World Series. He watched on TV as the Dodgers got swept by the Orioles.

“The Dodgers couldn’t have won the league flag without him, and they collapsed in the World Series because he wasn’t eligible,” Los Angeles Times columnist Sid Ziff wrote.

Long, winding road

Released by the Dodgers after the 1967 season, Schofield, 33, was signed by the reigning World Series champion Cardinals to be a backup to Dal Maxvill at shortstop and Julian Javier at second base.

Fifteen years after he accompanied Schofield on his ride to the ballpark on the rookie’s first day in the big leagues, Red Schoendienst, manager of the 1968 Cardinals, told the Post-Dispatch, “Schofield is the finest all-round utility infielder we’ve got on the club.”

Schofield made 17 starts at second base and 13 starts at shortstop for the 1968 Cardinals, who repeated as National League champions. On May 4, he contributed four hits and three RBI against the Giants. Boxscore

Schofield got into two games of the 1968 World Series against the Tigers but didn’t have a plate appearance.

Two months later, the Cardinals traded Schofield to the team he rooted for as a boy, the Red Sox. Schofield spent two seasons with the Red Sox and was dealt back to the Cardinals in October 1970.

In July 1971, the Cardinals traded Schofield, 36, for the third and last time, packaging him with Jose Cardenal and Bob Reynolds to the Brewers for Ted Kubiak and a prospect.

A son, also Dick Schofield, played 14 seasons as an infielder in the majors, and a grandson, Jayson Werth (Kim’s son), was a big-league outfielder for 15 seasons.

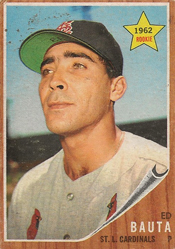

A right-handed sinkerball specialist, Bauta was a Pirates prospect when the Cardinals acquired him and second baseman

A right-handed sinkerball specialist, Bauta was a Pirates prospect when the Cardinals acquired him and second baseman  On July 31, 2012, the Cardinals acquired pitcher Edward Mujica from the Marlins for minor-league third baseman Zack Cox.

On July 31, 2012, the Cardinals acquired pitcher Edward Mujica from the Marlins for minor-league third baseman Zack Cox. On July 29, 2002, the Cardinals traded for Rolen, acquiring the third baseman, along with pitcher Doug Nickle, from the Phillies for infielder Placido Polanco and pitchers

On July 29, 2002, the Cardinals traded for Rolen, acquiring the third baseman, along with pitcher Doug Nickle, from the Phillies for infielder Placido Polanco and pitchers  In 1922, Doak pitched a pair of one-hitters for the Cardinals.

In 1922, Doak pitched a pair of one-hitters for the Cardinals. On July 19, 2002, the Cardinals acquired Finley from the Cleveland Indians for minor-league first baseman Luis Garcia and a player to be named. Three weeks later, the Cardinals sent another prospect, outfielder Coco Crisp, to the Indians, completing the deal.

On July 19, 2002, the Cardinals acquired Finley from the Cleveland Indians for minor-league first baseman Luis Garcia and a player to be named. Three weeks later, the Cardinals sent another prospect, outfielder Coco Crisp, to the Indians, completing the deal.