In 2025, Jim Kaat was interviewed by Jon Paul Morosi for the Baseball Hall of Fame podcast “The Road to Cooperstown.”

Here are excerpts:

Being enshrined in the Baseball Hall of Fame:

Being enshrined in the Baseball Hall of Fame:

Kaat: “I’m probably the only pitcher inducted based on longevity, dependability, accountability (rather than) dominance … There are a lot of guys who are there because they’re thoroughbreds, but there’s room for a Clydesdale as well.”

The secret to pitching 25 years (1959-83) in the big leagues:

Kaat: “I didn’t play Little League baseball. I didn’t really pitch organized baseball until I was about 15 _ American Legion ball in Michigan. Before that, we just had neighborhood kids, you’d get eight, 10 kids together, and go out and play … My sports were fast-pitch softball and bowling. Little did I know that those two exercises are great for the pitching arm … because your arm is going underhanded. I didn’t abuse my arm. Lucas Giolito (2019 all-star) threw 90 mph when he was 14 years old. He’s probably suffered through some injuries because of that. I probably threw 90 in my early 20s. There wasn’t an emphasis on velocity. It was movement and control.”

On youth baseball today:

Kaat: “It’s become so competitive. There is so much pressure on these young kids that I think a lot of times, by the time they’re 16, they’re probably burned out. A lot of it is the coaches and the parents … When I see the parents nowadays, they’re hanging on the fence, screaming at their kids, ‘Get the ball over.’ They’re paying big money to send these kids to these schools. They’ve taken the fun out of it. I never had to go through that. I think that’s a big reason I was able to pitch for a long time.”

On his father, John Kaat:

Kaat: “I have a picture on my desk of my dad standing in front of the Hall of Fame in 1947. He went to see Lefty Grove’s induction. That was his favorite player. He was an avid fan.”

On what he might have done if he didn’t become a big-league pitcher:

Kaat: “I’d have loved to have been a small-town high school basketball coach. You’d have a lot of influence on kids.”

On Twins teammate and fellow Hall of Famer Harmon Killebrew:

Kaat: “Harmon kind of set the tone for the behavior of the Twins … If you look at his penmanship, it’s the most immaculate, perfect, and he taught all the Twins players … He insisted, ‘Don’t you want to write your name so people know who you are?’ (Today) the Twins’ top-paid player, Carlos Correa, (signs) C.C. You don’t even know who it is.”

On Twins teammate and fellow Hall of Famer Rod Carew:

Kaat: “He took batting practice with us the end of 1966 and he was hitting some home runs. Then I think he found out that we didn’t care about exit velocity or launch angle … He was a magician with the bat. He changed his stance pitch to pitch. He moved all over the place. He got about some 30 bunt hits a year.”

On Twins teammate and fellow Hall of Famer Tony Oliva:

Kaat: “American League catchers in those days … would say the one guy we feared coming up in a clutch situation was Tony O. because Tony was that blend of power, average and speed.”

On Sandy Koufax, the Dodgers starter who opposed Kaat in Games 2, 5 and 7 of the 1965 World Series (Koufax won two of the three):

Kaat: “Happy to say he became a friend. He’s one of the (congratulatory) calls I got when I (was elected to) the Hall of Fame. We’ve stayed in touch. We’ve had some dinners together through (ex-Cardinal) Bill White, who was my broadcast mentor. He and Sandy live close to one another in the summer in Pennsylvania. I cross paths with Sandy a fair amount.”

On White Sox teammate and fellow Hall of Famer Dick Allen, who came up to the majors with the Phillies:

Kaat: “Had he been brought up in the Cardinals organization, where they had more black players, (Lou) Brock and (Curt) Flood, (Bob) Gibson, Bill White … it would have been easier for him … Dick suffered a lot in Philadelphia … It was tough for him as a black star in Philadelphia.”

On pitching for the Phillies (1976-79):

Kaat: “The end of my time in Philadelphia in 1979, I wasn’t pitching much. Danny Ozark was not a manager that had much confidence in guys who didn’t throw hard. I used to tell him, ‘Danny, Walter Johnson’s not around anymore.’ ”

On pitching in 62 games for the 1982 Cardinals at age 43 and being a part of a World Series championship team:

Kaat: “That was the most exciting team … The most enjoyable year I ever had … We hit 67 home runs as a team, stole 200 bases, had Bruce Sutter at the end of the games … To see that team play every day and the havoc it created for the opposition … Willie McGee would get on first. Boom! He’s on third … That was such a rush for me, waiting that long and to be a part of a team that … was totally foreign to the way the game is played today … Baseball came from the words base to base, and that’s what we did … That was the kind of baseball I was raised on.”

On what he told rookie pitcher John Stuper, who, with the Cardinals on the brink of elimination, pitched a four-hitter to beat Don Sutton and the Brewers in World Series Game 6:

Kaat: “I was kind of like a mentor to Stuper. I sat with him on the plane (after Game 5). I said, ‘Stupe, nobody expects you to win tomorrow. We’re facing Don Sutton. He’s going to the Hall of Fame. (Pretend) it’s a 10 o’clock in the morning exhibition game. Have some fun out there. Don’t worry about it.’ ”

On Cardinals teammate Keith Hernandez:

Kaat: “I don’t think there was ever a player I played with that was more intense on every play of the game … He kind of personified our team in that every play, every day, there was an intensity that’s hard to have over 162 games.”

On what he’s most proud of in his broadcasting career:

Kaat: “I learned from Tim McCarver to be honest and objective … Not being a homer.”

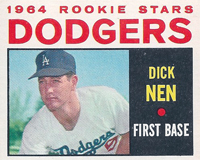

On Sept. 18, 1963, in his second at-bat in the majors, Nen slammed a home run for the Dodgers, tying the score in the ninth inning and stunning the Cardinals. The Dodgers went on to win, completing a series sweep that put them on the verge of clinching a pennant.

On Sept. 18, 1963, in his second at-bat in the majors, Nen slammed a home run for the Dodgers, tying the score in the ninth inning and stunning the Cardinals. The Dodgers went on to win, completing a series sweep that put them on the verge of clinching a pennant.

On May 4, 1910, Taft attended two big-league games that afternoon, watching an inning of a National League matchup, Reds versus Cardinals, at Robison Field before going to Sportsman’s Park to see some American League action between Cleveland and the Browns.

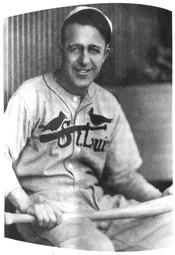

On May 4, 1910, Taft attended two big-league games that afternoon, watching an inning of a National League matchup, Reds versus Cardinals, at Robison Field before going to Sportsman’s Park to see some American League action between Cleveland and the Browns. A left-handed batter whose stroke regularly produced highly elevated line drives, Bottomley totaled 42 doubles, 20 triples and 31 home runs in 1928, the year he earned the National League Most Valuable Player Award and helped the Cardinals win their second pennant.

A left-handed batter whose stroke regularly produced highly elevated line drives, Bottomley totaled 42 doubles, 20 triples and 31 home runs in 1928, the year he earned the National League Most Valuable Player Award and helped the Cardinals win their second pennant. A 20-year-old reliever for a Cardinals farm club in Winston-Salem, N.C., Tiefenauer threw a knuckleball that had batters swinging at air. His manager,

A 20-year-old reliever for a Cardinals farm club in Winston-Salem, N.C., Tiefenauer threw a knuckleball that had batters swinging at air. His manager,