President William Howard Taft was a large man with a big appetite for food and baseball. During a visit to St. Louis, he was treated to generous portions of both.

On May 4, 1910, Taft attended two big-league games that afternoon, watching an inning of a National League matchup, Reds versus Cardinals, at Robison Field before going to Sportsman’s Park to see some American League action between Cleveland and the Browns.

On May 4, 1910, Taft attended two big-league games that afternoon, watching an inning of a National League matchup, Reds versus Cardinals, at Robison Field before going to Sportsman’s Park to see some American League action between Cleveland and the Browns.

A month earlier, at Washington, D.C., Taft became the first U.S. president to attend an Opening Day baseball game. He threw the ceremonial first pitch to Walter Johnson, who then crafted a one-hit shutout for the Senators in their victory against the Athletics. Boxscore

Described by the St. Louis Post-Dispatch as a “jovial baseball fan,” Taft attended 14 big-league games during his term (1909-13) as president, according to the book “Baseball: The Presidents’ Game.”

Athlete and student

Born and raised in the Mount Auburn neighborhood of Cincinnati, Taft “loved baseball and was a good second baseman and a power hitter” as a youth, according to Peri E. Arnold, professor emeritus of political science at the University of Notre Dame.

At Yale University, Taft was intramural heavyweight wrestling champion as a freshman, according to the National Constitution Center. (In 1997, he was inducted into the National Wrestling Hall of Fame in Stillwater, Okla.)

However, on the advice of his father, Taft gave up sports to focus on his studies. He graduated second in his class at Yale. Taft went to law school at the University of Cincinnati, became an attorney and then a judge in Ohio.

Encouraged by his wife Nellie to get into national politics, Taft accepted an offer from President William McKinley in 1900 to lead a commission to oversee the Philippine Islands.

As Peri E. Arnold noted, “Out of the victory in the Spanish-American War, the Philippine Islands had become a U.S. protectorate. McKinley wanted Taft to set up a civilian government. This entailed drafting and implementing laws, a constitution, an administration and a civil service bureaucracy.”

Taft improved the economy of the Philippine Islands, built roads and schools, and gave the Filipino people participation in government, according to the White House Historical Association.

In February 1904, President Theodore Roosevelt appointed Taft to the cabinet as secretary of war. “Taft became Roosevelt’s chief agent, confidant and troubleshooter in foreign affairs,” according to Peri E. Arnold. “He supervised the construction of the Panama Canal, made several voyages around the world for the president … and functioned as the provisional governor of Cuba.”

Taft served as secretary of war for four years before he accepted the Republican presidential nomination in June 1908. He won the election, defeating Democrat William Jennings Bryan, and was inaugurated in March 1909.

Motor man

President Taft’s main purpose for visiting St. Louis on May 4, 1910, was to address the Farmers Convention. His agenda for that Wednesday also included a businessmen’s luncheon, a dinner banquet with transportation leaders and the two baseball games.

The plan was to drive Taft from point to point during his stay. Taft was an automobile enthusiast. According to William Bushong of the White House Historical Association, “Taft believed in the future of the automobile and … was never happier than in the back seat of his touring car speeding through the countryside with the wind in his hair. Not required to observe speed limits or stop signs when driving the president, chauffeur George H. Robinson would blow the horn in advance of an intersection and fly through it.”

In 1910, most people didn’t have automobiles _ the number of cars in the U.S. then totaled 500,000 for a population of 92.2 million _ and driving laws still were being worked out.

For Taft’s drives through St. Louis, it was arranged for the fire department chief and four firemen with a chemical tank and hose to trail the president “on every foot of his journey,” the Post-Dispatch reported. “The police have agreed to waive the speed limit for one day and everywhere the president goes he will burn up the ozone at a terrific rate … There will be only one restriction on the president while here, and that is he must obey that part of the new traffic ordinance which directs automobiles to keep on the right side of the street at all times.”

Food for thought

Taft’s train from Cincinnati, where he attended the opening of the May Music Festival, arrived in St. Louis’ Union Station at 8:30 a.m. At least 1,000 uniformed St. Louis police officers, 75 plainclothes detectives and the entire 93-man mounted police force were called to duty, joining a Secret Service escort in providing protection for the president, the St. Louis Globe-Democrat reported.

From the train station, Taft was whisked to breakfast at the St. Louis Club on Lindell Boulevard. Taft weighed more than 300 pounds and he arrived in St. Louis hungry. For breakfast, he consumed two slices of corn bread, a portion of fish, two eggs on toast, three lamb chops, an olive, a radish, two pieces of celery and three cups of coffee, the Post-Dispatch reported.

Fortified, Taft was driven to the St. Louis Coliseum at Washington and Jefferson avenues for his 11 a.m. speech at the Farmers Convention. The Coliseum was a state-of-the-art entertainment and convention venue. Italian tenor Enrico Caruso performed there in April 1910 with the Metropolitan Opera Company.

After delivering his speech before a gathering of 8,000, Taft was driven to the Southern Hotel for a noon luncheon with the Business Men’s League. The menu featured soft shell crab, milk-fed chicken breast and strawberry melba.

Taft enjoyed a bowl of soup before the crab course was presented. He “took one bite of the crab and then put it aside,” the Post-Dispatch reported. “He refused to even look at the crab and for several minutes showed no interest in the meal. He glanced at a cucumber sandwich and bestowed an equal favor on some asparagus. The president’s eyes brightened considerably when he was brought a breast of milk-fed chicken. Seizing his knife and fork, he proceeded to show what a hungry man can do to a well-cooked chicken. Taft had his chicken finished before the others near him had fairly begun on theirs.”

Big fan

The end of lunch signaled it was time for baseball. In his remarks to the luncheon crowd, Taft said, “I attend baseball games for two reasons: First, I enjoy the game, and, second, I want to encourage it.”

On his way to Robison Field for the 3:30 game between the Reds and Cardinals, Taft stopped at the YWCA headquarters at Seventh and Olive streets and pledged support for the organization’s $400,000 building fund campaign.

At the ballpark, Taft took his place in a special box seat section built for him next to the Cardinals’ bench, the Globe-Democrat reported. He received a rousing reception from most of the 4,500 spectators, according to the newspaper.

It was pre-arranged that Taft would leave the game at 4 p.m.

After the Reds went down in order against hard-throwing Bob Harmon, the Cardinals teed off on a former teammate, Fred Beebe. Miller Huggins, whom the Cardinals acquired for Beebe, led off with a walk. Sending 10 batters to the plate, the Cardinals used four singles, three walks and some shoddy fielding by the Reds to score five runs in the first.

Then it was time for Taft to depart. He didn’t miss any suspense. The Cardinals scored seven runs in the third and cruised to a 12-3 triumph. Boxscore

The Browns led, 1-0, when Taft entered Sportsman’s Park in the third inning while Terry Turner was at bat for Cleveland. The game was halted and the players lined up to greet Taft as he walked past. Ten box seat sections were reserved for Taft and his entourage. Taft was provided a special chair, with ample width, on which to sit, the Globe-Democrat reported.

Most of the 4,200 spectators gave Taft an ovation before he settled in to watch the game. The Browns’ pitcher was Joe Lake, a Brooklyn native and former dockworker. Cy Young, 37, pitched for Cleveland.

The score still was 1-0 when Taft prepared to leave after the top of the fifth. As the president was exiting, Browns pitcher Rube Waddell, the eccentric former Athletics ace described by the Society for American Baseball Research as having “the intellectual and emotional maturity of a child,” ran to Taft and offered his hand. “Taft shook it heartily,” the Globe-Democrat reported.

Taft was in his suite at the Hotel Jefferson by 5 p.m. Meanwhile, the Browns kept playing. With the score tied, 3-3, the game was halted after 14 innings because of darkness. Boxscore

At a banquet in the hotel that night, Taft feasted on lake trout, filet mignon and frozen pudding before addressing members of the Traffic Club, mostly railroad executives and representatives of other transportation industries.

When he finished, printed copies of songs were placed at every plate and guests were encouraged to sing along as the orchestra played popular tunes. “The president sang with especial gusto when ‘Has Anybody Seen Kelly?,’ ‘Take Me Out To The Ballgame,’ ‘I’ve Got Rings On My Fingers, Bells On My Toes,’ and ‘Sun Bonnet Sue’” were rendered, the Globe-Democrat reported.

Then Taft was driven to Union Station, where he boarded his private railroad car attached to a Baltimore & Ohio train. When the train departed for Washington, D.C., at 1:45 a.m., Taft was sound asleep.

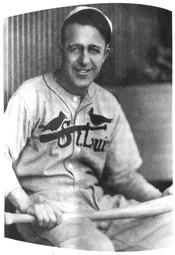

A left-handed batter whose stroke regularly produced highly elevated line drives, Bottomley totaled 42 doubles, 20 triples and 31 home runs in 1928, the year he earned the National League Most Valuable Player Award and helped the Cardinals win their second pennant.

A left-handed batter whose stroke regularly produced highly elevated line drives, Bottomley totaled 42 doubles, 20 triples and 31 home runs in 1928, the year he earned the National League Most Valuable Player Award and helped the Cardinals win their second pennant. A 20-year-old reliever for a Cardinals farm club in Winston-Salem, N.C., Tiefenauer threw a knuckleball that had batters swinging at air. His manager,

A 20-year-old reliever for a Cardinals farm club in Winston-Salem, N.C., Tiefenauer threw a knuckleball that had batters swinging at air. His manager,

On May 30, 1946, in the second game of an afternoon doubleheader against the Dodgers, Rowell launched a towering drive to right. The ball struck the Bulova clock high atop the scoreboard at Ebbets Field in Brooklyn, shattering the dial’s neon tubing and showering right fielder Dixie Walker with falling glass. As the New York Times put it, “The clock spattered minutes all over the place.”

On May 30, 1946, in the second game of an afternoon doubleheader against the Dodgers, Rowell launched a towering drive to right. The ball struck the Bulova clock high atop the scoreboard at Ebbets Field in Brooklyn, shattering the dial’s neon tubing and showering right fielder Dixie Walker with falling glass. As the New York Times put it, “The clock spattered minutes all over the place.” Ebbets Field was packed with 35,484 spectators, the Dodgers’ largest home crowd of 1946. (Years later, the New York Times, noting Bernard Malamud was a Brooklynite “who haunted Ebbets Field as a youth,” pondered whether he was at the game and whether his experiences there reflected any scenes he wrote in “The Natural.”)

Ebbets Field was packed with 35,484 spectators, the Dodgers’ largest home crowd of 1946. (Years later, the New York Times, noting Bernard Malamud was a Brooklynite “who haunted Ebbets Field as a youth,” pondered whether he was at the game and whether his experiences there reflected any scenes he wrote in “The Natural.”) The decision to switch from No. 45 to No. 9 was made by Robert Redford, the actor who portrayed Hobbs in the 1984 film. Redford did it to honor his favorite ballplayer,

The decision to switch from No. 45 to No. 9 was made by Robert Redford, the actor who portrayed Hobbs in the 1984 film. Redford did it to honor his favorite ballplayer,  In the book “My Greatest Day in Baseball,” Sisler recalled to Lyall Smith, “Walter still is my idea of the real baseball player. He was graceful. He had rhythm and when he heaved that ball in to the plate, he threw with his whole body so easy-like that you’d think the ball was flowing off his arm and hand … I was so crazy about the man that I’d read every line and keep every picture of him I could get my hands on.”

In the book “My Greatest Day in Baseball,” Sisler recalled to Lyall Smith, “Walter still is my idea of the real baseball player. He was graceful. He had rhythm and when he heaved that ball in to the plate, he threw with his whole body so easy-like that you’d think the ball was flowing off his arm and hand … I was so crazy about the man that I’d read every line and keep every picture of him I could get my hands on.”