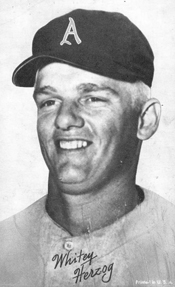

A player with the baseball smarts Whitey Herzog had didn’t need to be told when it was time to quit. It was autumn 1963. Herzog just turned 32, but his prime playing days had past. “His baseball epitaph could read: A Nice Guy Who Couldn’t Hit The Slow Curve,” Detroit columnist Joe Falls noted.

A journeyman outfielder, Herzog squeezed out every bit of talent he had, lasting eight seasons in the majors, mostly with losing teams, before the Tigers removed him from their big-league roster after the 1963 season. The Tigers offered him a role as player-coach at Syracuse, with a promise he’d be considered for a managerial job in their farm system some day, the Detroit Free Press reported. The Kansas City Athletics proposed he join them as a scout.

A journeyman outfielder, Herzog squeezed out every bit of talent he had, lasting eight seasons in the majors, mostly with losing teams, before the Tigers removed him from their big-league roster after the 1963 season. The Tigers offered him a role as player-coach at Syracuse, with a promise he’d be considered for a managerial job in their farm system some day, the Detroit Free Press reported. The Kansas City Athletics proposed he join them as a scout.

Herzog, though, was through with baseball. He could earn more ($16,000 a year) supervising construction workers for a company back home in Kansas City than he could coaching in the minors or pursuing prospects on the sandlots.

So Herzog took the construction job, but soon found he didn’t like it, mainly because he had little say in selecting the crew he was tasked with supervising. Hoping to trade his hard hat for a ball cap, Herzog asked the A’s if the scouting job still was open. It was, and he was hired to scout amateur players in 1964.

The scouting experience with the A’s, and then the Mets, gained Herzog a reputation as an astute talent evaluator and helped him develop the managing skills that would lead to his eventual election to the Baseball Hall of Fame.

Going pro

As a teen in New Athens, Ill., Herzog was a good basketball player. “Your basic small, scrappy guard,” he said in “White Rat,” his autobiography. Herzog received seven college basketball scholarship offers, but he wanted to play pro baseball. He could run, throw and hit a fastball.

The St. Louis Browns made an offer: no signing bonus, a minor-league salary of $200 a month and a chance to pitch. Herzog said no. Actually, he claimed in his autobiography, he said to Browns scout Jack Fournier, “Now I know why you guys are in last place all the time, if you wanted to sign a wild-ass left-hander like me.”

On the day after he graduated from high school in 1949, Herzog was invited to a Yankees tryout camp in Branson, Mo. The Yankees told him he could make it as an outfielder. Heck, they said, Joe DiMaggio would be retiring just about the time Herzog should be ready for the majors. (What he didn’t know is that another prospect, Mickey Mantle, was signing with the Yankees in 1949, too.) Herzog took the Yankees’ offer of a $1,500 bonus and a minor-league salary of $150 a month.

Years later, Herzog told the Kansas City Star, “If I had gotten more money, it would have been all right, but I was foolish to sign for that kind of a bonus. I could have gone out and broken my leg the first year, and then where would I have been? If I had it to do over, I would have gone to college (on a basketball scholarship) and then signed a baseball contract.”

Tough breaks

Herzog played five seasons in the Yankees’ farm system and served a two-year Army hitch. He never did appear in a regular-season game for the Yankees, but he got to know their manager, Casey Stengel, during 1955 and 1956 spring training and developed a fondness for him. “Of all the managers I’ve ever played for, Casey had the most influence on me,” Herzog said in his autobiography. “Casey took a liking to me, spent a lot of time with me.”

On Easter Sunday in 1956, after attending a church service with Yankees players Tony Kubek and Bobby Richardson, Herzog was called up to Stengel’s hotel suite. “When I got there,” Herzog recalled in his autobiography, “I saw that Casey had already been celebrating Easter with a few drinks. He was rambling on.”

After a while, Stengel blurted out that Herzog was going to the majors _ with the Washington Senators. “Go over there and have a good year,” Stengel told him, “and I’ll get you back.”

As Herzog noted in his book, “I never had that good year, and I never wore the pinstripes in Yankee Stadium. In my heart, though, I was always a Yankee. I never got over the fact that they’d traded me.”

Herzog was with the Senators (1956-58), A’s (1958-60) and Orioles (1961-62) before being traded to the Tigers in November 1962. Going to Detroit meant he’d do a lot of sitting, not playing. Herzog was an outfielder and first baseman, and the Tigers had standouts with Rocky Colavito in left, Bill Bruton in center, Al Kaline in right and Norm Cash at first base. “There was no use kidding myself _ all those guys were better ballplayers than I was,” Herzog told the Kansas City Times.

To pass the time, Herzog told teammates he would keep count of the home runs he hit in batting practice all season.

“I hit my 250th in Detroit in late August,” Herzog told Kansas City journalist Joe McGuff. “(Coach) Bob Swift was pitching that day. I hit my 249th into the upper deck in right field. (Teammate) Gates Brown was standing by the batting cage and I told Gates I was really going to crank up and see if I could hit my 250th on the roof. Sure enough, I did. There was an usher nearby and I asked if he’d mind going up on the roof and getting the ball for me. He found it and brought it back. The ball landed in a big patch of tar. So it looked legitimate. I got it autographed (by teammates) and fixed up and I’ve got it in a trophy case at home.”

In Baltimore, on the day before the 1963 season finale, Herzog hit his 299th batting practice homer. “Everybody on the club knew I was going for my 300th on the last day,” he said, “so they told me I could keep hitting until I got 300. It rained that day and they had to call off batting practice, so I wound up with 299.”

A tiger in batting practice, Herzog was a pussycat in the games that season. He hit no homers and batted .151. “You’ll find no nicer guy on the Tigers than Whitey Herzog,” Joe Falls of the Detroit Free Press informed readers, “and it grieves us to see him struggling so much at the plate.”

Talent hunt

Jim Gleeson left the A’s scouting department to join the coaching staff of Yankees manager Yogi Berra, creating the opening for Herzog to quit the construction job and return to baseball.

Herzog displayed the same desire and determination for scouting amateurs as he had for playing in the pros. In June 1964, he told the Kansas City Star, “Last month, I saw 52 high school and college games. I’ve been averaging about 1,500 miles a week on the road. I’ve been seeing the country.”

Though he was competing with other scouts to sign talent, Herzog earned their respect. The scouts welcomed him into the fraternity and offered their advice on how to succeed.

“The old scouts like Bert Wells of the Dodgers and Fred Hawn of the Cardinals took him under their wing and really helped him,” Herzog’s colleague, Joe McDonald, recalled to Cardinals Yearbook in 2010. “He always talked about them. It’s not easy doing amateur scouting for the first time. You have to find ballparks (and) call the coach in advance to try to determine if the pitcher you want to see is pitching. You have to do all that preliminary work. Whitey did all that, which was a great foundation (to managing), because his evaluating skills matched his strategic ability in game situations. That was the key.”

The best of the 12 prospects Herzog signed in 1964 were Chuck Dobson, who went on to pitch nine seasons in the American League and won 74 games, and catcher Ken Suarez, who played seven seasons in the majors, including 1973 with the Rangers when Herzog managed them.

The one who got away was pitcher Don Sutton, the future Hall of Famer. “I had him in my hotel room, ready to sign an A’s contract for $16,000,” Herzog said in his autobiography. “What a bargain he would have been.”

The deal needed the approval of Charlie Finley, but the A’s owner wouldn’t go over $10,000. “I went out and told Bert Wells of the Dodgers that he ought to sign him,” Herzog said. The Dodgers did and Sutton went on to pitch 23 seasons in the majors, winning 324 games and pitching in four World Series, including three with the Dodgers and one with the Brewers against Herzog’s 1982 Cardinals.

Wise judge

After rejecting an offer to become head baseball coach at Kansas State, Herzog coached for the A’s in 1965 and for the Mets in 1966. He scouted pro talent as a special assistant to Mets general manager Bing Devine in 1967, then was promoted to director of player development. “The people in the organization reached the point where they relied more and more on my judgment about who to sign and who to get rid of,” Herzog said in his autobiography.

After the Mets vaulted from ninth-place finishers in 1968 to World Series champions in 1969, Herzog went to the victory party at Shea Stadium to congratulate manager Gil Hodges. In recalling the moment years later to Cardinals Yearbook, Herzog said, “When he saw me coming, he jumped out of his chair and said, ‘I want to congratulate you. Every time I’ve called you and asked for a ballplayer, you’ve sent me the right one.’ That meant a lot to me.”

Later, when Herzog managed the Royals to three division titles and then led the Cardinals to three National League pennants and a World Series championship, his skill as a talent evaluator often was cited as a significant factor in his success.

“It wasn’t just Whitey’s ability to manage a game,” Jim Riggleman, a coach on Herzog’s St. Louis staff before becoming a big-league manager, told Cardinals Yearbook. “There are other good game managers. It was his ability to evaluate talent. He knew who could play and who was on the last leg.”

Red Schoendienst, who managed St. Louis to two pennants and a World Series title before coaching for Herzog, said to Cardinals Yearbook, “You manage according to what you have. That’s what managing is all about, knowing your ballplayers … Whitey had a lot of practice judging players … He could see the kind of abilities they had and whether they just came out to play or if they were winners … Some guys just know how to win. Those are the guys you want.”

Here are excerpts:

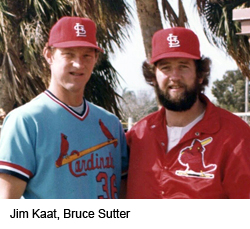

Here are excerpts: Jim Kaat and Lee Smith were the starters in the Cardinals versus Cubs game on June 26, 1982, at Chicago. Kaat got the win and Smith took the loss in a 2-1 St. Louis triumph. The save went to Bruce Sutter. All three pitchers would be elected to baseball’s shrine in Cooperstown, N.Y.

Jim Kaat and Lee Smith were the starters in the Cardinals versus Cubs game on June 26, 1982, at Chicago. Kaat got the win and Smith took the loss in a 2-1 St. Louis triumph. The save went to Bruce Sutter. All three pitchers would be elected to baseball’s shrine in Cooperstown, N.Y. Being enshrined in the Baseball Hall of Fame:

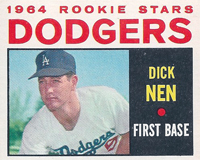

Being enshrined in the Baseball Hall of Fame: On Sept. 18, 1963, in his second at-bat in the majors, Nen slammed a home run for the Dodgers, tying the score in the ninth inning and stunning the Cardinals. The Dodgers went on to win, completing a series sweep that put them on the verge of clinching a pennant.

On Sept. 18, 1963, in his second at-bat in the majors, Nen slammed a home run for the Dodgers, tying the score in the ninth inning and stunning the Cardinals. The Dodgers went on to win, completing a series sweep that put them on the verge of clinching a pennant.