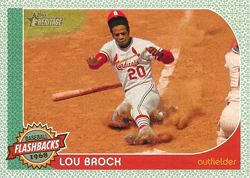

On his 37th birthday, Lou Brock hit an inside-the-park home run.

Brock hit nine home runs inside the park _ three with the Cubs and six with the Cardinals. He was 22 when he hit the first and 38 when he hit the ninth.

Brock hit nine home runs inside the park _ three with the Cubs and six with the Cardinals. He was 22 when he hit the first and 38 when he hit the ninth.

Brock had the power to hit balls over the walls at any big-league ballpark and also the speed to circle the bases on balls hit inside the park.

Out of the park

The first time Brock hit a big-league home run was on April 13, 1962, for the Cubs in their home opener against the Cardinals at Wrigley Field in Chicago. Leading off the bottom of the first inning against rookie Ray Washburn, Brock hit a pitch over the bleachers in right-center and onto Sheffield Avenue. The ball carried at least 450 feet, according to the St. Louis Post-Dispatch.

“Two years ago, I batted against Washburn in the NAIA (National Association of Intercollegiate Athletics) tournament and all I got were three strikeouts and a little bunt single,” Brock told the Post-Dispatch. “When I told the boys at Southern U. last winter that I would have to face Washburn in the majors, they asked me if I was going to jump behind the water cooler and hide when he pitched.” Boxscore

(Brock had six hits in 14 career at-bats in the big leagues versus Washburn _ a .429 batting mark. Brock and Washburn were Cardinals teammates from 1964-69, playing on three National League pennant winners and two World Series championship teams.)

Friendly Forbes Field

Four days after his homer against Washburn, Brock hit his second home run, and his first inside the park, against the Pirates’ Tom Sturdivant at Wrigley Field. Boxscore

Brock “sped around the bases while Donn Clendenon was chasing the ball in the left field corner,” the Chicago Tribune reported.

Sturdivant again was the pitcher when Brock hit his next inside-the-park homer on April 23, 1963, at Pittsburgh’s Forbes Field. Boxscore

Brock’s drive to center struck the wire screen of a light tower (the screen, or cage, was in play) and bounded back past center fielder Bill Virdon. Brock circled the bases as Willie Stargell retrieved the ball.

A right-hander who played 10 years in the majors and pitched in six World Series games for the Yankees, Sturdivant was no match for Brock. In seven career plate appearances versus Sturdivant, Brock had four hits and two walks _ an on-base percentage of .857.

Three months later, on July 21, 1963, Brock hit his second inside-the-park homer of the season, and the third of his career, against the Pirates’ Don Cardwell at Forbes Field. The drive hit the center field wall. Boxscore

Igniting the offense

In June 1964, Brock was traded to the Cardinals and transformed the lineup with his hitting, speed and intimidating base running.

Brock’s first Cardinals home run was launched onto the pavilion roof in right at the original Busch Stadium in St. Louis against the Giants’ Jack Sanford on June 21, 1964.

Brock’s second Cardinals home run was inside the park _ again at Forbes Field _ versus the Pirates’ Steve Blass in the first game of a July 13 doubleheader.

Batting second in the order, between Curt Flood and Dick Groat, Brock hit a shot that landed in deep right-center, bounced against an iron gate, and caromed away from right fielder Roberto Clemente. Brock scored without a slide ahead of the relay throw from Bill Mazeroski. Boxscore

Brock’s performance in the doubleheader illustrated his multiple skills. In the second game, he powered a home run into the upper deck in right. He totaled seven hits, a walk, two RBI and five runs scored in the doubleheader. Boxscore

For his career, Brock hit .299 with six home runs in 79 games at Forbes Field, which was the Pirates’ home until July 1970.

(Brock wasn’t alone in finding the large outfield at Forbes Field to be good for hitting homers inside the park. The Cardinals’ Terry Moore hit two in one game there in 1939.)

Hit and run

From 1965 to 1975, Brock hit two homers inside the park _ on May 22, 1965, versus the Mets’ Jack Fisher at the original Busch Stadium, and on May 3, 1970, against the Astros’ Tom Griffin at Busch Memorial Stadium.

In 1976, Brock hit two inside-the-park homers.

The first of those came on June 18, his 37th birthday, and it was the second homer hit inside the park by a Cardinals batter that night at Busch Memorial Stadium.

In the fourth inning, the Cardinals’ Hector Cruz hit a pitch from the Padres’ Randy Jones deep to left-center. As Willie Davis leaped for it, he banged into the wall and the ball careened back toward the infield. Cruz circled the bases as Davis chased the ball, and scored just ahead of the relay throw from Enzo Hernandez.

Brock batted in the next inning against Jones and hit a drive to right-center. The ball got past Dave Winfield, hit a seam in the artificial surface, bounced over Davis, who was backing up the play, and rolled to the wall. Brock raced around the bases before Tito Fuentes could make a relay throw to the plate. Boxscore

“All in a day’s work _ a hard day’s work,” Brock said to the Post-Dispatch.

Asked about achieving the feat at 37, Brock replied to the Associated Press, “Age don’t mean nothing. It’s only when you can’t do the job any more that it counts.”

Three months later, on Sept. 8, 1976, Brock hit another homer inside the park at St. Louis. The pitcher was the Expos’ Chuck Taylor, Brock’s former Cardinals teammate.

Brock’s final inside-the-park homer was hit on Sept. 21, 1977, against the Expos’ Hal Dues at Montreal. Boxscore

The career leader in inside-the-park home runs is Jesse Burkett, who played in the majors from 1890 to 1905. He hit 55 inside-the-park homers, including 19 with the Cardinals and eight with the Browns.

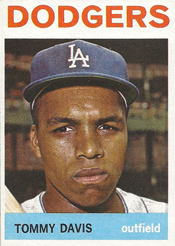

A two-time National League batting champion who totaled 2,121 hits, Davis batted .167 versus Gibson, but made a lasting impression on the Cardinals’ ace with those game-winning homers.

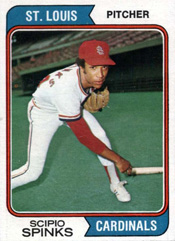

A two-time National League batting champion who totaled 2,121 hits, Davis batted .167 versus Gibson, but made a lasting impression on the Cardinals’ ace with those game-winning homers. On April 15, 1972, in a swap of pitchers, the Cardinals sent Jerry Reuss to the Astros for Spinks and Lance Clemons.

On April 15, 1972, in a swap of pitchers, the Cardinals sent Jerry Reuss to the Astros for Spinks and Lance Clemons. Stargell struck out swinging in seven consecutive plate appearances versus the Cardinals in September 1964.

Stargell struck out swinging in seven consecutive plate appearances versus the Cardinals in September 1964. On April 11, 1932, six months after they became World Series champions, the Cardinals dealt left fielder Chick Hafey to the Reds for pitcher Benny Frey, first baseman Harvey Hendrick and cash.

On April 11, 1932, six months after they became World Series champions, the Cardinals dealt left fielder Chick Hafey to the Reds for pitcher Benny Frey, first baseman Harvey Hendrick and cash. On April 6, 1982, the Cardinals scored six runs against Ryan, knocking him from the game after three innings, and rolled to a 14-3 victory over the Astros at Houston.

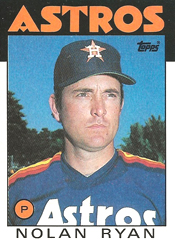

On April 6, 1982, the Cardinals scored six runs against Ryan, knocking him from the game after three innings, and rolled to a 14-3 victory over the Astros at Houston.