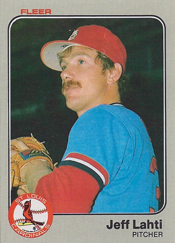

A trade for a minor-league pitcher gave the Cardinals a lift in their quest for a World Series championship.

On April 1, 1982, the Cardinals acquired Jeff Lahti and another minor-league pitcher, Oscar Brito, from the Reds for big-league pitcher Bob Shirley.

On April 1, 1982, the Cardinals acquired Jeff Lahti and another minor-league pitcher, Oscar Brito, from the Reds for big-league pitcher Bob Shirley.

Called up to the Cardinals two months later, Lahti added valuable depth to a bullpen featuring Bruce Sutter, Jim Kaat and another ex-Red, Doug Bair.

Promising prospect

Born and raised in Oregon, Lahti was taken by the Reds in the fifth round of the 1978 amateur baseball draft. A right-hander, he became a reliable reliever in the minors, posting ERAs of 2.67 in 1979, 2.77 in 1980 and 2.97 in 1981.

“Lahti has very good ability, and he has that intangible _ competitiveness,” Reds manager John McNamara told the Dayton Journal Herald in 1981.

After watching Lahti pitch for Class AAA Indianapolis in 1981, Cardinals scout Mo Mozzali recommended him.

A chance to acquire Lahti came during spring training in 1982 when left-hander Dave LaPoint earned a position on the Cardinals’ pitching staff as a spot starter and reliever.

LaPoint’s performance made left-hander Bob Shirley expendable. For the Cardinals in 1981, Shirley was 6-4, including 2-0 against the Reds. Including his four seasons with the Padres before being dealt to the Cardinals, Shirley had a 12-7 record and two saves versus the Reds.

When the Reds learned Shirley was available, they agreed to send Lahti and Brito, another right-hander, to the Cardinals.

“This was a big decision for us to make to give up two young prospects like this,” Reds general manager Dick Wagner told the Cincinnati Enquirer. “Brito is one of the highest-regarded prospects in the game, period. They were very important to us. It was a tough decision.”

Fired up

The Cardinals assigned Lahti and Brito to Class AAA Louisville to begin the 1982 season. In June, Lahti was called up when reliever Mark Littell accepted a demotion to Louisville.

Lahti, 25, brought a rookie’s enthusiasm that was embraced by the contending Cardinals. Between pitches, he “stomps around the mound like a bull protecting a pasture,” Hal McCoy wrote in the Dayton Daily News.

“I try to keep myself pumped up, but I’m not conscious of my actions,” Lahti told the St. Louis Post-Dispatch. “Maybe it’s my second being. They say there are two sides to everybody. Maybe that’s my second side. On the mound, I’m a monster.”

On July 16, 1982, in a game Shirley started for the Reds, Lahti won for the first time in the majors, pitching 3.1 innings in relief of Steve Mura before Bruce Sutter came in to close.

In the ninth, when Sutter got Paul Householder to ground into a double play, Lahti raced from the dugout onto the field. “He was halfway to the foul line before realizing there were only two outs,” the Dayton Daily News reported.

Lahti called his first big-league win “the thrill of my life.”

“I never thought my first victory would be against the Reds,” he said. “I always thought it would be for them.” Boxscore

Getting it done

On Aug. 9, 1982, Lahti pitched six scoreless innings in relief of Dave LaPoint for a win against the Mets. Cardinals manager Whitey Herzog told the Post-Dispatch, “I like him because he comes in and gets after people. He’s a good jam pitcher.” Boxscore

From then on, according to the Cardinals media guide, Herzog referred to Lahti as “Jam Man” for his ability to work out of tight situations.

A month later, on Sept. 18, Lahti again pitched six innings of relief for a win versus the Mets. Boxscore

In his last five regular-season appearances, totaling 4.1 innings, Lahti yielded one run, helping the Cardinals secure a division title for the first time.

Lahti was 5-4 with a 3.91 ERA in 33 games for the 1982 Cardinals. Excluding his one start, his season ERA as a reliever was 3.04.

Key contributor

Bob Shirley finished 8-13 in 1982, his lone season with the Reds. He went on to pitch for the Yankees and Royals.

Oscar Brito never made it to the big leagues.

Despite persistent shoulder pain, Lahti pitched well for the Cardinals from 1982 through 1985. He led them in saves (19) and ERA (1.84) in 1985, and was the winning pitcher in the pivotal Game 5 of the National League Championship Series which ended on Ozzie Smith’s iconic walkoff home run. Boxscore

After apearing in four games in 1986, Lahti underwent shoulder surgery. “The surgeon found a torn rotator cuff, with which Lahti had pitched for several years, and also bone chips that no one had detected before,” the Post-Dispatch reported.

The shoulder never regained full strength and Lahti’s pitching career was finished.

His career numbers with the Cardinals: 17-11 record, 20 saves and a 3.12 ERA. Against the Reds, Lahti was 4-1 with a save and a 1.66 ERA.

According to the Post-Dispatch, Lahti returned to Hood River Valley in Oregon, operated a bottling company, owned an apple orchard and coached baseball.

Terry’s heart may have been with the Cardinals, but he went on to pitch in five World Series with the Yankees and was involved in two of the most dramatic Game 7 finishes.

Terry’s heart may have been with the Cardinals, but he went on to pitch in five World Series with the Yankees and was involved in two of the most dramatic Game 7 finishes. With the designated hitter being used in the National League for the first time in 2022, it may be a while before the Cardinals pick a pitcher to be a pinch-hitter. Even if a pitcher was needed to bat, the odds would be against him getting a hit after a long layoff as a batter.

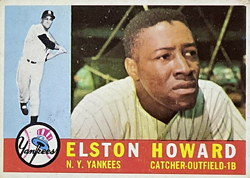

With the designated hitter being used in the National League for the first time in 2022, it may be a while before the Cardinals pick a pitcher to be a pinch-hitter. Even if a pitcher was needed to bat, the odds would be against him getting a hit after a long layoff as a batter. It was an audacious attempt, coming two months after a World Series in which Howard hit .462 and Ford pitched a pair of shutouts, but Cardinals general manager Bing Devine indicated the Yankees gave him reason to try.

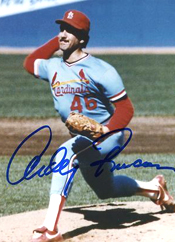

It was an audacious attempt, coming two months after a World Series in which Howard hit .462 and Ford pitched a pair of shutouts, but Cardinals general manager Bing Devine indicated the Yankees gave him reason to try. In March 1982, the Cardinals were counting on right-hander Andy Rincon to be a consistent winner.

In March 1982, the Cardinals were counting on right-hander Andy Rincon to be a consistent winner. With the Washington Redskins, Taylor was “the man who had given more headaches to cornerbacks than any pass catcher to play the game,” according to the Washington Post.

With the Washington Redskins, Taylor was “the man who had given more headaches to cornerbacks than any pass catcher to play the game,” according to the Washington Post.