In his quest to pitch for the Cardinals, Bob Slaybaugh lost an eye, but not his determination.

On March 24, 1952, Slaybaugh was pitching batting practice at Cardinals spring training when he was struck in the head by a line drive. He suffered severe damage to his left eye and it had to be surgically removed.

On March 24, 1952, Slaybaugh was pitching batting practice at Cardinals spring training when he was struck in the head by a line drive. He suffered severe damage to his left eye and it had to be surgically removed.

A couple of months later, Slaybaugh was pitching again.

Promising prospect

Robert Slaybaugh was born and raised in the village of Hartville, Ohio, located about halfway between Akron and Canton. According to census records and his obituary, the family name was spelled Slabaugh. At some point, either intentionally or inadvertently, a “y” was added to the spelling of his last name.

Known as Bob or Bobby, Slaybaugh was stricken by rheumatic fever as a youth and had to use a wheelchair for a time, according to baseball-reference.com.

A left-handed pitcher who stood 5 feet 9, Slaybaugh developed into a pro prospect and was signed by the Cardinals. In his first season, 1950, he was 6-17 with a 4.85 ERA for Goldsboro, N.C., a Class D farm team. He returned to Goldsboro in 1951, became the ace (17-10, 2.33 ERA) and led the league in strikeouts (224 in 219 innings, according to the St. Louis Post-Dispatch).

The Cardinals rewarded Slaybaugh with an invitation to attend big-league spring training at St. Petersburg, Fla., in 1952.

Described by the St. Petersburg Times as a “quiet, likeable, team-type player,” Slaybaugh roomed at the Bainbridge Hotel with another pitcher, Gary Blaylock.

“Residents along lower Second Avenue South became accustomed to seeing the two stroll toward the Bainbridge each evening after games, so absorbed in replaying the contest that they stopped from time to time to demonstrate by gestures what had occurred,” the St. Petersburg Times observed.

Slaybaugh got into two Cardinals exhibition games, pitching two innings against the Senators and three versus the Braves. He allowed one run, showing Cardinals manager Eddie Stanky enough to convince him “he was only a year or two away” from being ready for the majors, the St. Petersburg Times noted.

“Right back at me”

On March 24, 1952, it was Slaybaugh’s turn to pitch batting practice during morning drills for rookies and prospects. Jim Dickey, a power-hitting first baseman at the Class A level, stepped in from the left side of the plate. Slaybaugh threw a pitch on the outside corner.

“I was expecting it to be pushed down the left field line as usual,” Slaybaugh told Helen Popa for The Sporting News. “Instead, it shot right back at me. I watched it all the way and threw my gloved hand in front of my face for protection, but at the same moment I jerked my head. The ball tipped one of my gloved fingers and hit the left side of my face.”

Slaybaugh “dropped as though shot,” the St. Petersburg Times reported.

According to The Sporting News, “the line drive shattered the left cheekbone and forced the left eyeball partly out of the socket.”

Stanky and Don McGranaghan, a vacationing New York state police officer, rushed Slaybaugh to a hospital in McGranaghan’s car, Bob Broeg reported in the St. Louis Post-Dispatch.

“With a towel, Stanky literally held the eye in place,” according to Broeg.

Stanky told The Sporting News, “In the car on the way to the hospital, he talked about baseball. No whimper out of him, and the pain must have been terrific. He told me that, if they had to operate, for me to be sure to tell the surgeons that he had rheumatic fever when he was young, so they could be careful about the effect of anesthetic on the heart.”

Significant damage

A St. Louis ophthalmologist, Dr. S. Albert Hanser, happened to be vacationing in nearby North Reddington Beach. A police escort raced him to the hospital, according to the St. Petersburg Times.

Dr. Hanser joined St. Petersburg ophthalmologist Dr. Bernard Bell in treating Slaybaugh. They performed “a delicate operation” in an effort to save the left eye, the Associated Press reported.

In addition to the damaged eye, Dr. Hanser said Slaybaugh suffered a fracture of the left cheekbone, a fracture of a group of bones near the eye and multiple fractures of the nasal bones, the St. Louis Globe-Democrat reported.

Cardinals owner Fred Saigh called Slaybaugh’s parents in Ohio, informed them of their son’s injury and arranged for them and another son to travel by plane to St. Petersburg the next day, The Sporting News reported.

After a week in the St. Petersburg hospital, Slaybaugh, accompanied by his mother, took a flight to St. Louis on March 31 for further treatment at a hospital there. That same day, Jim Dickey, who hit the line drive, was assigned by the Cardinals to their Rochester farm team. He’d never make it to the majors.

On April 4, Slaybaugh’s damaged eye was removed in “an emergency operation,” the Associated Press reported. Dr. Hanser, who performed the operation, said, “A rupture at the rear of the eyeball forced the removal.”

Passing grade

Sometimes, good can come amid tragedy. While recuperating from his eye operation in the St. Louis hospital, Slaybaugh met a nurse, Joy, and she became his wife, according to The Sporting News.

In late April, Slaybaugh was cleared to practice with the Cardinals at Sportsman’s Park.

“When I first started working out, I was ready to give up,” he told The Sporting News. “I couldn’t do anything right. I was confused by distances and was just plain scared, but Eddie Stanky and the players kept encouraging me and gradually I started feeling better.”

In mid-May, Slaybaugh was discharged from the hospital. He made a brief visit home to Ohio, then reported to the Cardinals’ Omaha farm team, managed by George Kissell.

Ray Oppegard, business manager of the Omaha team, said, “(Slaybaugh) still thinks he can pitch and so do we and our doctors.”

Kissell wasn’t so sure. Asked in May by the Des Moines Tribune whether he’d let Slaybaugh pitch in a game, Kissell said, “Too dangerous. A one-eyed person has no depth perception.”

When Slaybaugh arrived in Omaha, he said to Kissell, “I didn’t come here to sit on the bench. Let me pitch.”

According to The Sporting News, Kissell set up a program to help determine Slaybaugh’s chances of playing again. He had Slaybaugh throw on the sideline. After several good sessions, Slaybaugh was allowed to stand behind the pitcher during batting practice to get used to batted balls again.

After that, Slaybaugh progressed to pitching in bunting practice, then batting practice.

“At first, he threw the ball only to the inside corner so that he knew when it was hit it wouldn’t come back at him,” Kissell told The Sporting News. “Now he throws all over the plate.”

Kissell then put Slaybaugh through fielding practices. “He had his players drive grounders straight at Slaybaugh and to both sides,” the Des Moines Tribune reported. “Then he tested him with line drives.”

Finally, Slaybaugh got to bat in batting practice. When he passed all the tests to Kissell’s satisfaction, it was time to play in games.

Quite a comeback

On June 22, in his first game since losing the eye, Slaybaugh allowed one run in 6.1 innings of relief against Colorado Springs.

His next appearance, on June 29, was a start against Des Moines in the first game of a doubleheader. Slaybaugh responded with a four-hit shutout in a 1-0 Omaha victory in seven innings.

“That shows you what determination and courage will do,” Des Moines manager Harry Strohm told the Des Moines Tribune.

Slaybaugh called it “the biggest game of my life.”

He pitched 31 innings for Omaha in 1952 and posted a 2-2 record, according to baseball-reference.

The next year, he was 2-9 for Columbus (Ga.) and Winston-Salem. On May 1, he tried to pitch for the first time without an eye patch, placing a strip of tape over the left optic. In the fifth inning, the artificial eye fell to the ground. “Unflustered, Bobby picked it up and stuck it in his pocket,” The Sporting News reported.

The 1954 season was Slaybaugh’s last as a pro. After brief stints with Columbus (Ga.) and Lynchburg (Va.), the Cardinals asked him to report to Winnipeg, Canada. “Instead, he went home and obtained a job as a bookkeeper with a produce firm,” according to The Sporting News.

On March 26, 1952, the Cardinals claimed Mauch for $10,000 after he was placed on waivers by the Yankees.

On March 26, 1952, the Cardinals claimed Mauch for $10,000 after he was placed on waivers by the Yankees. On March 22, 1962, in the usually relaxed setting of spring training, an impromptu encounter between Maris, the Yankees’ outfielder, and Hornsby, the Mets’ hitting coach, turned ugly before an exhibition game at St. Petersburg, Fla.

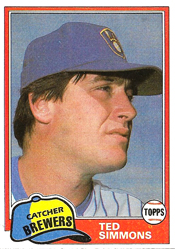

On March 22, 1962, in the usually relaxed setting of spring training, an impromptu encounter between Maris, the Yankees’ outfielder, and Hornsby, the Mets’ hitting coach, turned ugly before an exhibition game at St. Petersburg, Fla. Instead, he decided to stay with the American League Brewers.

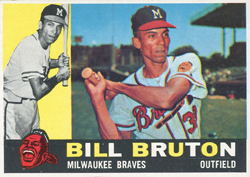

Instead, he decided to stay with the American League Brewers. A left-handed batter, Bruton became the Braves’ center fielder in 1953 and helped transform them into National League champions in 1957 and 1958.

A left-handed batter, Bruton became the Braves’ center fielder in 1953 and helped transform them into National League champions in 1957 and 1958.  It happened on May 12, 1962, in a game Koufax started for the Dodgers against the Cardinals. Gibson and Drysdale relieved and were the winning and losing pitchers in a 15-inning, 6-5 Cardinals victory.

It happened on May 12, 1962, in a game Koufax started for the Dodgers against the Cardinals. Gibson and Drysdale relieved and were the winning and losing pitchers in a 15-inning, 6-5 Cardinals victory.