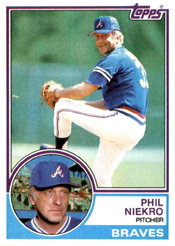

Unwanted by Joe Torre and Bob Gibson with the Braves, Phil Niekro was coveted by the Cardinals.

Looking to bolster their starting pitching in 1984, the Cardinals made a pitch to Niekro, who asked for and received his release from the Braves after they told him he wasn’t in their plans.

Looking to bolster their starting pitching in 1984, the Cardinals made a pitch to Niekro, who asked for and received his release from the Braves after they told him he wasn’t in their plans.

Niekro was approaching his 45th birthday, but the Cardinals, and other clubs, were confident the knuckleball pitcher remained effective.

Old pro

In 1983, Niekro, 44, had a poor start to the season. After a loss to the Astros on June 21, his record was 2-6 with a 5.04 ERA.

“On 3-and-2 counts, he didn’t trust his knuckleball and, turning to his fastball, now semi-fast, he was often only setting himself up,” columnist Furman Bisher observed in The Sporting News.

Braves manager Joe Torre and pitching coach Bob Gibson lost confidence in Niekro, but, lacking a better option, kept him in the rotation.

Niekro and his knuckleball warmed with the weather. On Aug. 24, he beat the Cardinals, limiting them to two runs in seven innings. Boxscore

“I’m a better pitcher in the second half of the season,” Niekro told the St. Louis Post-Dispatch. “In the spring, I go out there and seem to try to throw the knuckleball through the catcher’s mitt. When it gets hot, it makes you slow down and think a lot better.”

Niekro finished the season 11-10 with a 3.97 ERA in 201.2 innings pitched. He was 1-1 with a 2.45 ERA in three starts against the Cardinals. It was the 16th time Niekro had achieved double-digit wins in a season for the Braves.

Power vs. finesse

Niekro’s good finish didn’t change the minds of Torre and Gibson. They informed Braves owner Ted Turner they didn’t want Niekro in the starting rotation in 1984.

Turner met with Niekro, suggested it was time to quit playing and offered him his choice of other jobs, including a chance to manage in the minors. Niekro said Turner also told him he would override the decision of Torre and Gibson if Niekro wanted, but Niekro instead asked for his release.

“The coaching staff does not want me to pitch here,” Niekro said to the Atlanta Constitution. “I’m not going into spring training holding Ted Turner’s hand, pitching under his shadow.”

Referring to Gibson, Niekro told Chris Mortensen of the Atlanta Constitution, “One of the coaches thought I should have retired in May or June. This coach stated, ‘Phil Niekro is 100 years old and he ought to quit right now.’ “

Regarding Torre, who was Niekro’s catcher in the 1960s, Niekro said, “I’ve gotten along with him about as well as any manager I’ve had. I just haven’t gotten along as well when it comes to pitching.”

Tim Tucker of the Atlanta Constitution wrote, “A lot of it has to do with the almost fanatical preference of Joe Torre and Bob Gibson for power pitchers. They simply would rather not have a knuckleballer on the staff.”

In his book “Stranger to the Game,” Gibson said, “I had been of the opinion that our talented young pitchers would be more of an asset to the ballclub than Niekro at age 45.

“I certainly believed in an organization’s loyalty to its cornerstone players, but at some point loyalty steps aside and good judgment takes over.”

Fitting in

Niekro’s unceremonious departure surprised many. Gibson acknowledged, “The Niekro affair had made me an unpopular figure in town and in certain parts of the front office.”

Noting that Niekro won his fifth Gold Glove Award in 1983, columnist Bill Conlin of The Sporting News wrote, “Niekro’s knuckleball is undiminished, he’s still among the best at holding runners on first and fielding his position, and he’s the kind of individual any manager would like to have around a young pitching staff.”

The Phillies’ Pete Rose told the Atlanta paper, “Are you telling me the Braves think they have 10 better pitchers than Phil Niekro? if so, I haven’t seen them.”

Pitcher Gaylord Perry said, “If he can get a park that suits his style, he can win 15 to 17 games again.”

The Cardinals considered Busch Memorial Stadium that kind of ballpark.

Of the five teams that pursued Niekro, the Cardinals appeared to have the strongest interest. Other suitors were the A’s, Pirates, White Sox and Yankees.

Niekro became a target after a proposed trade in which the Cardinals would send Neil Allen, Ken Oberkfell and Jim Adduci to the Orioles for Dennis Martinez, Tim Stoddard and Benny Ayala didn’t materialize, according to The Sporting News.

Money matters

At the 1983 baseball winter meetings, Cardinals manager Whitey Herzog said, “I’d like to have Phil Niekro.”

Cardinals general manager Joe McDonald told The Sporting News, “I would think Phil would want to pitch somewhere where he would get the ball regularly. He’d get the ball with us.”

Niekro wanted to play in a World Series before he retired and the Cardinals had won the title in 1982.

McDonald said Herzog determined Glenn Brummer, backup to starting catcher Darrell Porter, would be best suited to handle the knuckleball and catch Niekro.

According to the Post-Dispatch, the Cardinals offered Niekro his choice of one-year offers. One was for a flat salary of just less than $500,000. The other had incentives that could increase the total contract to more than $500,000.

Atlanta Constitution sports editor Jesse Outlar wrote, “It’s the guess here that he’ll be on the Cardinals’ payroll before Christmas. Niekro mentions the Cardinals frequently during conversations.”

According to the Post-Dispatch, Niekro’s brother, Joe, an Astros pitcher, told a sports banquet that Phil’s first choice was the Cardinals.

It was a bit surprising then when on Dec. 30 Niekro and his agent, Bruce Church, declined both Cardinals offers.

“All I can say is their interest in Phil was not followed up with what I would consider to be reasonable financial opportunities,” Church said to the Atlanta Constitution.

McDonald told the Post-Dispatch, “I thought we made an outstanding offer considering everything.”

A week later, Niekro accepted a two-year, $1.4 million offer from the Yankees. In addition to the guaranteed $700,000 per season, the contract included incentives that could increase Niekro’s annual income to more than $800,000, according to the Atlanta Constitution. The deal also included a no-trade clause.

“I don’t think anybody in their right mind could have turned this down,” Niekro said.

Niekro, who turned 45 in April 1984, was 16-8 for the Yankees in 1984 and 16-12 for them in 1985. Video

In “Stranger to the Game,” Gibson said, “It turned out Niekro did have some good pitching left in him and he still could have been valuable to the Braves, but in his absence younger arms like Rick Mahler’s and Pascual Perez’s came along nicely.”

Niekro pitched for the Indians in 1986. In 1987, when he was 48, Niekro was with the Indians and Blue Jays before finishing his playing career with a start for the Braves in Atlanta against the Giants. Boxscore

An outfielder who played 10 seasons (1970-79) in the majors, primarily with the Pirates and Cubs, Clines hit for average and ran well.

An outfielder who played 10 seasons (1970-79) in the majors, primarily with the Pirates and Cubs, Clines hit for average and ran well. Green had successes, but his drinking held him back, and his recklessness had devastating consequences.

Green had successes, but his drinking held him back, and his recklessness had devastating consequences. On Feb. 14, 1952, Cain was acquired by the Browns in a trade with the Tigers.

On Feb. 14, 1952, Cain was acquired by the Browns in a trade with the Tigers. On Feb. 7, 2012, Cora signed a minor-league contract with the Cardinals, who invited him to spring training to compete for a spot on their Opening Day roster.

On Feb. 7, 2012, Cora signed a minor-league contract with the Cardinals, who invited him to spring training to compete for a spot on their Opening Day roster. In 1962, Gotay was the Cardinals’ starting shortstop.

In 1962, Gotay was the Cardinals’ starting shortstop.