Nearly 40 years before the 1984 movie “The Natural” transformed fictional baseball character Roy Hobbs into a pop culture icon, Bama Rowell of the Boston Braves did what Hollywood screenwriters only could imagine.

On May 30, 1946, in the second game of an afternoon doubleheader against the Dodgers, Rowell launched a towering drive to right. The ball struck the Bulova clock high atop the scoreboard at Ebbets Field in Brooklyn, shattering the dial’s neon tubing and showering right fielder Dixie Walker with falling glass. As the New York Times put it, “The clock spattered minutes all over the place.”

On May 30, 1946, in the second game of an afternoon doubleheader against the Dodgers, Rowell launched a towering drive to right. The ball struck the Bulova clock high atop the scoreboard at Ebbets Field in Brooklyn, shattering the dial’s neon tubing and showering right fielder Dixie Walker with falling glass. As the New York Times put it, “The clock spattered minutes all over the place.”

In the film version of “The Natural,” Roy Hobbs, portrayed by actor Robert Redford, clouted a ball into the outfield lights, sending an explosion of sparks into the night. Hobbs’ walkoff home run clinched the pennant for the fictitious New York Knights. Movie clip

(In Bernard Malamud’s superior 1952 novel “The Natural,” Hobbs strikes out.)

Bama Rowell’s clock-shattering shot was a ground-rule double, not a home run, and it came in the second inning for a team on its way to a fourth-place finish in an eight-team league.

Good hit, no field

Carvel William Rowell was from Citronelle, Alabama. Once the territory of the Chickasaw tribe, the town was named for the citronella grass prevalent in the area. Citronella oil is a popular insect repellent.

A high school and semipro pitcher, Rowell also was a prep football, basketball and track standout. He accepted a football scholarship to Louisiana State University, but before he had a chance to play for the varsity, he signed a pro baseball contract, according to the Mobile (Ala.) Register.

Because he could hit, Rowell was converted into a second baseman in the minors, but fielding was a struggle. Playing in the Dodgers’ system in 1938, he made 64 errors _ 12 in 17 games with Winston-Salem and 52 in 114 games with Dayton.

After the season, baseball commissioner Kenesaw Mountain Landis declared Rowell a free agent on a technicality. (His transfer from Winston-Salem to Dayton hadn’t been filed properly.)

Despite his fielding woes, the Boston Braves were impressed by the .310 batting mark, 30 doubles and 23 stolen bases Rowell produced for Dayton. Jocko Munch, a Braves representative, handed him a wad of 20 $50 bills. Rowell pocketed the $1,000 and signed with Boston.

Sent to minor-league Hartford in 1939, Rowell became an outfielder. He still couldn’t cope with balls that bounced his way. In desperation, he tried dropping to a knee. “You’re using the wrong knee,” outfielder Johnny Cooney told him. According to the Boston Globe, Rowell replied, “I knowed something was wrong.”

His Hartford teammates hung the Bama nickname on him. “They used to kid me about being from Alabama and the name happened to stick,” Rowell told the Minneapolis Star Tribune.

Casey takes a chance

Called up to Boston in September 1939, Rowell made 14 outfield starts. Early in the 1940 season, Boston manager Casey Stengel moved Sibby Sisti from second to third and put Rowell at second base.

(In a serendipitous twist, Sisti went on to have a role as the Pittsburgh manager in the film, “The Natural.”)

Stengel was well aware of Rowell’s shortcomings as a fielder (“The ball runs up his arm and you expect it to jump in a pocket like a little white rat,” Stengel told Harold Kaese of the Globe), but the manager took a liking to the rookie.

“The kid’s got a natural double play arm,” Stengel said to the Dayton Journal Herald. “He can whip that ball right across his chin while pivoting … He’s fast and he hustles … I’d like to see him make it. He’s a good kid.”

Rowell committed 30 errors during the 1940 season, but hit .305. In a June game against the Cardinals, he had three hits and three errors. In another game versus St. Louis in September, he drove in six runs. Boxscore and Boxscore

“He’s one of the best hitters in the National League,” Cardinals pitcher Lon Warneke told the Globe in August 1940. “He hasn’t got the power some other hitters have, but there isn’t anybody in our league that’s any tougher to get out.”

Rowell followed up with 60 RBI for Boston in 1941 (the team leader had 68) but made 40 errors at second base.

On Dec. 4, 1941, three days before the Japanese attack on Pearl Harbor, Rowell was inducted into the U.S. Army. He served in artillery duty during World War II and missed four baseball seasons before he was discharged from the military in October 1945.

Stop a clock

When Rowell returned to the Braves at 1946 spring training, Casey Stengel was gone and Billy Southworth was the manager. Southworth joined Boston after leading the Cardinals to three consecutive National League pennants and two World Series titles.

Southworth shifted Rowell, 30, from second base to the outfield. A left-handed batter, Rowell played primarily against right-handed pitchers. Southworth tried him in the fourth, second and fifth spots in the batting order. Then, for the May 30 doubleheader at Brooklyn, Rowell was put in the leadoff position.

In the opener, Rowell went hitless against Kirby Higbe. Boxscore

A rookie, Hank Behrman, started Game 2 for Brooklyn. Rowell led off by grounding out. In the second, with the score tied at 2-2, Boston had runners on first and third, one out, when Rowell came to the plate again.

Ebbets Field was packed with 35,484 spectators, the Dodgers’ largest home crowd of 1946. (Years later, the New York Times, noting Bernard Malamud was a Brooklynite “who haunted Ebbets Field as a youth,” pondered whether he was at the game and whether his experiences there reflected any scenes he wrote in “The Natural.”)

Ebbets Field was packed with 35,484 spectators, the Dodgers’ largest home crowd of 1946. (Years later, the New York Times, noting Bernard Malamud was a Brooklynite “who haunted Ebbets Field as a youth,” pondered whether he was at the game and whether his experiences there reflected any scenes he wrote in “The Natural.”)

Behrman gave Rowell a pitch to his liking and he lofted it toward the scoreboard. It was common for batters to smack balls off the scoreboard in the Ebbets Field bandbox, but none had soared into the Bulova clock since it was installed atop the scoreboard in 1941.

Rowell’s drive smacked into the clock at 4:25 p.m. Because the scoreboard was in play, Rowell’s blast was a ground-rule double. It drove in the go-ahead run and knocked Behrman from the game.

“The clock continued to run for an hour, but stopped when the hand reached the spot that Bama’s ball had hit,” The Sporting News reported.

Bulova had promised a watch to any batter who hit the clock. Forty-one years later, in 1987, while doing research for a magazine article about home runs, sports reporter Bert Sugar read about Rowell’s smash off the Ebbets Field clock. When he tracked down Rowell, 71, in Citronelle, Alabama, the ex-ballplayer told him, “I never did get no watch.”

Sugar contacted Bulova officials and told them about the oversight. After persistent pestering from Sugar, a Bulova representative presented Rowell a watch in a ceremony in Rowell’s hometown on July 28, 1987. Boxscore

Clock runs out

A back ailment hampered Rowell in 1946. “It got so bad at one time that he couldn’t bend over to pick up a groundball,” the Globe reported.

The next year, platooning again in the outfield, he made 12 errors in left. At spring training in 1948, Rowell went to the Dodgers in the trade that brought Eddie Stanky to Boston. Stanky helped the Braves become National League champions in 1948. Rowell spent a few days with the Dodgers, who decided to send him to minor-league Montreal. When Rowell objected to the demotion, the Dodgers moved him to the Phillies.

The 1948 season was Rowell’s last in the majors. During his time in the National League, he hit .381 against Carl Hubbell, clouted home runs versus Johnny Vander Meer and Lon Warneke, smacked five hits in a game against the Phillies and three doubles in a game versus the Cubs, but, for pure drama, nothing topped his clock-smashing shot in Brooklyn.

The decision to switch from No. 45 to No. 9 was made by Robert Redford, the actor who portrayed Hobbs in the 1984 film. Redford did it to honor his favorite ballplayer,

The decision to switch from No. 45 to No. 9 was made by Robert Redford, the actor who portrayed Hobbs in the 1984 film. Redford did it to honor his favorite ballplayer,  In the book “My Greatest Day in Baseball,” Sisler recalled to Lyall Smith, “Walter still is my idea of the real baseball player. He was graceful. He had rhythm and when he heaved that ball in to the plate, he threw with his whole body so easy-like that you’d think the ball was flowing off his arm and hand … I was so crazy about the man that I’d read every line and keep every picture of him I could get my hands on.”

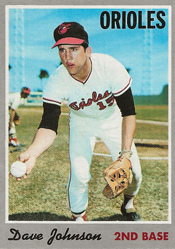

In the book “My Greatest Day in Baseball,” Sisler recalled to Lyall Smith, “Walter still is my idea of the real baseball player. He was graceful. He had rhythm and when he heaved that ball in to the plate, he threw with his whole body so easy-like that you’d think the ball was flowing off his arm and hand … I was so crazy about the man that I’d read every line and keep every picture of him I could get my hands on.” “I found that if I hit second, instead of seventh, we’d score 50 or 60 more runs and that would translate into a few more wins,” Johnson told the Baltimore Sun. “I gave it to him (Weaver), and it went right into the garbage can.”

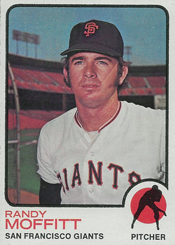

“I found that if I hit second, instead of seventh, we’d score 50 or 60 more runs and that would translate into a few more wins,” Johnson told the Baltimore Sun. “I gave it to him (Weaver), and it went right into the garbage can.” On July 8, 1974, at Jarry Park in Montreal, Moffitt pitched 3.1 scoreless innings against the Expos and was credited with a win.

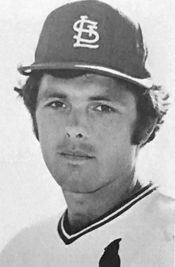

On July 8, 1974, at Jarry Park in Montreal, Moffitt pitched 3.1 scoreless innings against the Expos and was credited with a win. Hill threw with the strength and quick release of Johnny Bench. He worked well with pitchers, caught pop flies and dug balls out of the dirt.

Hill threw with the strength and quick release of Johnny Bench. He worked well with pitchers, caught pop flies and dug balls out of the dirt.