When push came to shove during a game at Cincinnati, both the Cardinals and the plate umpire behaved badly.

On April 22, 1952, Cardinals manager Eddie Stanky confronted umpire Scotty Robb, who responded with a shove.

On April 22, 1952, Cardinals manager Eddie Stanky confronted umpire Scotty Robb, who responded with a shove.

Two weeks later, Robb submitted his resignation to National League president Warren Giles, then accepted a surprise offer to continue umpiring in the American League.

Law and order

A Baltimore native, Douglas Walker Robb, known as Scotty, played semipro baseball until an arm injury prompted him to move into umpiring. He umpired college and minor-league games before serving two years (1944-45) in the Navy.

Robb was 38 when he became a National League umpire in August 1947. In his debut game, Cardinals versus Giants at the Polo Grounds in New York, he umpired at third base. Johnny Mize drove in four runs against his former club, powering the Giants to a 6-5 victory. Boxscore

Three years later, on July 2, 1950, Robb had a confrontation with Stanky in a game between the Braves and Giants at the Polo Grounds.

With the score tied at 2-2 in the seventh inning, the Giants had a runner on first, none out, when Stanky came to the plate with “visions of a game-winning rally,” the New York Daily News reported.

Nicknamed “The Brat,” Stanky got upset when Robb, working the plate, called Bob Chipman’s first pitch to him a strike. Stanky took an angry swing at the next delivery and missed badly. Strike two. After watching a pitch go outside, Stanky grounded into a rally-killing double play.

“Angrier than ever when he reached the bench, Stanky threw a couple of water buckets onto the grass,” the Daily News reported, and Robb ejected him.

Giants manager Leo Durocher came out of the dugout to argue and Robb tossed him, too.

As Stanky and Durocher made the long walk across the outfield to the clubhouse behind the bleachers in center, Giants outfielder Bobby Thomson threw a towel in the direction of Robb and he also was ejected.

In a flash, the Giants had lost their second baseman, center fielder and manager.

“It was a senseless rhubarb and strictly the Giants’ fault,” declared the Boston Globe.

Robb took “a wicked booing” from Giants fans the remainder of the game, the Globe noted, especially after the Braves struck for four runs in the ninth and won, 6-3. Boxscore

Boiling point

The Giants traded Stanky, 36, to the Cardinals in December 1951 and he became their player-manager, replacing Marty Marion.

After the Cardinals split their first six games in 1952, Stanky selected rookie pitcher Vinegar Bend Mizell, 21, to make his big-league debut in a start against the Reds at Crosley Field.

Mizell, who allowed the Reds two runs in the first and none for the rest of the game, showed more poise than Stanky and some of his veteran players.

In the third inning, Robb, the plate umpire, called out the Cardinals’ Solly Hemus on strikes for the second time in the game. Hemus barked at Robb before heaving his bat toward the grandstand on the first-base side near the visitors’ dugout.

Robb ejected Hemus, prompting Stanky to rush out of the dugout. Robb ordered Stanky to leave the field, but instead he got as close as he could to the umpire. Stanky stood toe to toe with Robb, gestured excitedly, waved his index finger in his face and berated him, the Cincinnati Enquirer reported.

“I wanted to know why Hemus was put out of the game,” Stanky told the St. Louis Globe-Democrat.

According to the Dayton Journal Herald, Stanky and Robb “were jostling each other in a startling fashion.”

During what the Globe-Democrat described as a “tornadic argument,” Robb thought Stanky touched or bumped him.

According to Bob Broeg of the St. Louis Post-Dispatch, “As far as press box observers could tell, it was a phantom touch, as light-fingered and as unobtrusive as a pickpocket.”

Stanky said to the Globe-Democrat, “I told Robb that I never touched him. If I did, it was not intentional, and probably was caused by the fact that his momentum as he was walking toward our dugout carried him into me.”

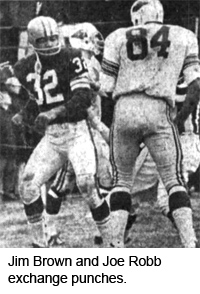

Enraged, Robb threw down his mask, put both hands on Stanky’s chest and vigorously shoved him back a few steps. “The umpire squared off and Stanky, obviously stunned, then started toward Robb,” the Post-Dispatch reported.

“It appeared as if the two might start swinging at each other,” the Globe-Democrat noted.

Umpires joined Cardinals players and coaches in getting between the two and preventing further damage.

Stanky told the Post-Dispatch, “Getting shoved that way and not being able to strike back was the most embarrassing, the most humiliating thing that’s ever happened to me on a ball field.”

Robb ejected Stanky and the game continued. Gene Mauch replaced Hemus at shortstop.

Stan the Mad

More trouble happened in the seventh. With the Cardinals trailing, 2-1, Stan Musial batted with two outs and a runner on first. Musial hit a grounder sharply down the line at first. Umpire Lon Warneke, Musial’s former Cardinals teammate, ruled it a foul ball. “From the press box, the ball appeared to be foul by at least two feet,” the Cincinnati Enquirer noted.

Musial thought otherwise.

“Stan, who seldom protests a decision, kicked the dirt viciously several times,” the Globe-Democrat reported.

According to the Post-Dispatch, Musial was “drop-kicking dirt with the skill of a football field goal specialist.”

Perhaps to prevent Musial from getting ejected for the only time in his career, Cardinals reliever Al Brazle ran from the bullpen onto the field to argue on Musial’s behalf. Warneke ejected Brazle. Boxscore

Tough job

National League president Warren Giles was at the game and witnessed the shenanigans. The next day, Giles met for 45 minutes with Stanky, Hemus and the four umpires _ Robb, Warneke, Babe Pinelli and Dusty Boggess _ to get their versions of what happened.

As the meeting ended, Robb and Stanky shook hands. “It’s all over now,” Stanky told The Sporting News. “We’ll forget it and start anew.”

A few hours later, Giles, a former Cardinals minor-league executive, announced he was fining Hemus $25 and Stanky $50 for their roles in the incident. Giles publicly reprimanded Robb and said he fined the umpire an amount greater than the combined fines of Hemus and Stanky. Years later, The Sporting News reported Robb was fined $200.

Robb “seemed to feel he had been humiliated by Giles’ reprimand and fine,” The Sporting News reported.

The next game Robb worked was on April 26 when the Cardinals played the Cubs at St. Louis. In the seventh inning, Warneke ejected Stanky for arguing a call at third base. Boxscore

Unable to overcome the feeling that Giles hadn’t supported him, Robb resigned on May 5 and said he would operate a printing business in New Jersey.

Two days later, Robb was stunned when American League president Will Harrirdge offered him an umpiring job.

“When Mr. Harridge approached me with an offer, I was so choked up I couldn’t talk for a minute or two,” Robb told The Sporting News.

Harridge said, “I signed what I believed to be a good umpire and the kind of gentleman we would like to have on our staff.”

Robb umpired in the American League through June 1953, then retired from baseball at age 44.

“It’s a lonesome, difficult life,” Robb told The Sporting News. “An umpire must live like a hermit, avoiding casual acquaintances and not associating with players, managers or coaches. The travel is bad … and the pay wasn’t too good either.”

The incident occurred on Dec. 19, 1965, in the regular-season finale between the Cardinals and Cleveland Browns at Busch Stadium in St. Louis.

The incident occurred on Dec. 19, 1965, in the regular-season finale between the Cardinals and Cleveland Browns at Busch Stadium in St. Louis. On Jan. 4, 1972, the Cardinals signed Maloney, hoping he could join a starting rotation with Gibson, Steve Carlton and Jerry Reuss.

On Jan. 4, 1972, the Cardinals signed Maloney, hoping he could join a starting rotation with Gibson, Steve Carlton and Jerry Reuss. A prime example of how Schoendienst put team ahead of individual occurred on July 22, 1968, when the Cardinals trailed the Phillies by two runs in the bottom of the ninth inning.

A prime example of how Schoendienst put team ahead of individual occurred on July 22, 1968, when the Cardinals trailed the Phillies by two runs in the bottom of the ninth inning. On Dec. 18, 2001, Martinez joined La Russa on the Cardinals.

On Dec. 18, 2001, Martinez joined La Russa on the Cardinals. On Dec. 9, 1931, the reigning World Series champion Cardinals acquired outfielder Hack Wilson and pitcher Bud Treachout from the Cubs for pitcher Burleigh Grimes.

On Dec. 9, 1931, the reigning World Series champion Cardinals acquired outfielder Hack Wilson and pitcher Bud Treachout from the Cubs for pitcher Burleigh Grimes.