(Updated June 9, 2024)

(Updated June 9, 2024)

The Cardinals weren’t looking to trade for outfielder Lonnie Smith. The deal fell into their laps.

On Nov. 19, 1981, the Cardinals obtained Smith in a three-way trade with the Indians and Phillies. The Indians sent catcher Bo Diaz to the Phillies for Smith and a player to be named (pitcher Scott Munninghoff). The Indians then swapped Smith to the Cardinals for pitchers Lary Sorensen and Silvio Martinez.

Smith and another outfield newcomer, Willie McGee, became the catalysts of the Cardinals’ offense, igniting the team’s run to the 1982 National League pennant and World Series championship.

Mix and match

Whitey Herzog, who had the dual role of Cardinals manager and general manager, sought to swap two unhappy players, shortstop Garry Templeton and outfielder Sixto Lezcano, after the 1981 season. Herzog wanted a shortstop and starting pitcher in return.

Neither the Indians nor the Phillies seemed a likely trade partner for the Cardinals. The Indians wanted pitching and the Phillies needed a catcher. Neither was looking for Templeton or Lezcano.

Bo Diaz of the Indians was the catcher the Phillies coveted. Phillies scout Hugh Alexander rated Diaz “the best-throwing catcher in the major leagues,” the Philadelphia Daily News reported. Phillies manager Pat Corrales, a former catcher, managed Diaz during winter baseball in Venezuela and viewed him as a successor to Bob Boone.

The Indians, who had catchers Ron Hassey and Chris Bando, were willing to trade Diaz, but the Phillies didn’t have the pitching needed to get him.

An offer you can’t refuse

A pitcher the Indians wanted was Lary Sorensen, who was 7-7 with a 3.27 ERA for the 1981 Cardinals. Sorensen had seasons of 12, 15 and 18 wins for the Brewers before being traded to the Cardinals in December 1980.

Indians general manager Phil Seghi “has long been a fan of” Sorensen, The Sporting News reported, “and continually pestered the Cardinals” about dealing him. The Indians didn’t have what it took to get Sorensen from the Cardinals, but the Phillies suggested a creative solution. They thought the Cardinals would like Lonnie Smith.

The Cardinals were solid in right field with George Hendrick, but planned to try rookie David Green in center in 1982 and go with a platoon of Dane Iorg and Tito Landrum in left.

The Phillies, figuring Smith would be an upgrade for the Cardinals in either center or left, suggested sending Smith to the Indians for Diaz, and, in turn, the Indians would swap Smith to the Cardinals for Sorensen.

In his book, “White Rat: A Life in Baseball,” Herzog said Phil Seghi called Cardinals assistant general manager Joe McDonald and asked whether the club would be interested in Lonnie Smith.

McDonald relayed the message to Herzog: “(Seghi) says he needs pitching more than he needs Lonnie Smith, and you can have him for Silvio Martinez and Lary Sorensen.”

Herzog replied, “Get (Seghi) on the phone and make that deal right now.”

“All we gave up was two guys who didn’t figure to pitch much for us anyway,” Herzog said. “It’s deals like that which make you look like a genius.”

As good as advertised

In Philadelphia, the trade “provoked a firestorm of fan outrage that lit the Phillies’ switchboard like the White House Christmas tree,” the Philadelphia Daily News reported. Smith was “the club’s most explosive young offensive player.”

Smith finished the 1981 season with a 23-game hitting streak. The year before, he batted .339 with 33 stolen bases for the World Series champions. The Phillies planned to replace him with rookie Bob Dernier.

Though “shocked and disappointed” to be traded, Smith said to the Philadelphia Daily News, “I’m glad to go to a team that can beat the Phillies.”

After acquiring Lonnie Smith, the Cardinals traded Templeton and Lezcano to the Padres and got another important player, shortstop Ozzie Smith, and starting pitcher Steve Mura.

Lonnie Smith settled into left field for the Cardinals and Willie McGee, called up from the minors in May to replace injured David Green, became the center fielder.

The 1982 Cardinals won the National League East Division title, finishing three games ahead of the runner-up Phillies, and Smith had a lot to do with it. He led the league in runs scored (120). He also led the Cardinals in hits (182), doubles (35), stolen bases (68), batting average (.307) and total bases (257).

In the 1982 World Series, when the Cardinals prevailed in seven games versus the Brewers, Lonnie Smith batted .321 with nine hits, including four doubles and a triple, and six runs scored. Video

“Lonnie was a very tough ballplayer, very good hitter,” Herzog told Cardinals Magazine. “Below average defensively, below average arm, but … a good offensive player. He could bust up the double play as good as anybody in the league.”

When left fielder and speedster Vince Coleman emerged as a force for the Cardinals, Lonnie Smith was traded to the Royals in May 1985.

Though he battled cocaine addiction, Lonnie Smith went on to play 17 seasons in the majors and appeared in a total of five World Series _ one each for the Phillies, Cardinals and Royals, and two with the Braves.

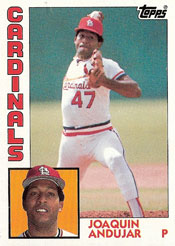

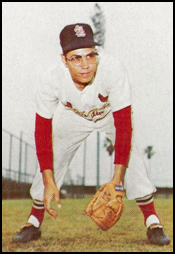

On Nov. 13, 1981, Joaquin Andujar became a free agent after finishing the 1981 season with the Cardinals.

On Nov. 13, 1981, Joaquin Andujar became a free agent after finishing the 1981 season with the Cardinals. On May 17, 1970, Johnny Bench was the Reds’ center fielder in the second game of a doubleheader against the Braves at Cincinnati. For Bench, the National League’s Gold Glove-winning catcher, it was the first time he played the outfield in a major-league game.

On May 17, 1970, Johnny Bench was the Reds’ center fielder in the second game of a doubleheader against the Braves at Cincinnati. For Bench, the National League’s Gold Glove-winning catcher, it was the first time he played the outfield in a major-league game. During spring training in 1964, the Cardinals were in the market for a backup catcher and the Braves were seeking a reserve outfielder.

During spring training in 1964, the Cardinals were in the market for a backup catcher and the Braves were seeking a reserve outfielder. In March 1965, the Cardinals were considering trading Javier, their second baseman since 1960. Anderson, three weeks into his job as a manager in the Cardinals’ farm system, spoke up at an organizational staff meeting and advocated for keeping Javier.

In March 1965, the Cardinals were considering trading Javier, their second baseman since 1960. Anderson, three weeks into his job as a manager in the Cardinals’ farm system, spoke up at an organizational staff meeting and advocated for keeping Javier. On Oct. 23, 1996, St. Louis County health officials said four employees of Bartolino’s South restaurant at 5914 South Lindbergh Boulevard were diagnosed with the highly contagious hepatitis A disease.

On Oct. 23, 1996, St. Louis County health officials said four employees of Bartolino’s South restaurant at 5914 South Lindbergh Boulevard were diagnosed with the highly contagious hepatitis A disease.