Hal Smith, a Cardinals catcher in the 1950s, had a significant role in the club’s success in the 1980s.

On Oct. 21, 1981, the Cardinals got minor-league outfielder Willie McGee from the Yankees for pitcher Bob Sykes. The Cardinals made the trade on the recommendation of Smith, a Cardinals scout, who watched McGee play for the Yankees’ Nashville farm club and liked what he saw.

On Oct. 21, 1981, the Cardinals got minor-league outfielder Willie McGee from the Yankees for pitcher Bob Sykes. The Cardinals made the trade on the recommendation of Smith, a Cardinals scout, who watched McGee play for the Yankees’ Nashville farm club and liked what he saw.

McGee went on to become one of the Cardinals’ best and most popular players, using his hitting, fielding and speed to help them win three National League pennants and a World Series title.

Pining for pinstripes

McGee was 17 and recently graduated from high school in 1976 when the White Sox selected him in the June amateur baseball draft. McGee was chosen in the seventh round, just after the Tigers took Ozzie Smith and just before the Red Sox selected Wade Boggs.

If McGee had signed with the White Sox, he eventually might have made his debut in the majors for Tony La Russa, who became White Sox manager in August 1979. Instead, McGee decided to attend community college.

The decision appeared to be shrewd when the Yankees took him in the first round of the secondary phase of the draft in January 1977, “but, unwise to the ways of negotiating contracts, he wound up signing for less than the White Sox had offered him,” the St. Louis Post-Dispatch reported.

“I probably could have got more if I knew what I was doing,” McGee said.

In 1978, his second season in the Yankees’ system, McGee, a natural right-handed batter, started switch-hitting.

He was considered a promising prospect when he got to Class AA Nashville in 1980, but in July he suffered a broken jaw and was limited to 78 games for the season. McGee hit .283. Designated hitter Buck Showalter, the future big-league manager, led Nashville in batting average (.324) and hits (178) in 1980.

Odd man out

The Yankees put McGee on their 40-man big-league winter roster after the 1980 season, but in December they signed free-agent outfielder Dave Winfield and needed to open a spot for him.

McGee was one of two players the Yankees considered dropping from their roster. The other was his best friend on the Nashville team, Ted Wilborn, a switch-hitting outfielder who played briefly with the Blue Jays and Yankees.

Yankees vice president for baseball operations Bill Bergesch, a former Cardinals minor-league executive who signed Bob Gibson to his first pro contract, told the New York Daily News, “We liked Willie. We considered him a fine prospect, but our minor-league people liked the other player (Wilborn) better.”

McGee said to The Tennessean newspaper, “Somebody had to go and I was the least experienced.”

By being reassigned outright to Nashville, McGee was frozen on the minor-league roster and couldn’t be recalled by the Yankees.

Good report card

McGee, Wilborn and Don Mattingly formed the Nashville outfield in 1981. McGee led Nashville in batting (.322) and had 24 stolen bases. Mattingly batted .316 and led the club in hits (173). Wilborn hit .295 and had 43 steals.

Hal Smith, the Cardinals’ starting catcher from 1956-60, was scouting the Nashville team extensively because the Yankees were looking to make a deal for Cardinals pitcher Bob Sykes.

During the 1981 season, “a proposed trade with the Yankees that would have involved Sykes fell through,” the Post-Dispatch reported, but the clubs were hopeful of reviving the deal after the season.

Cardinals executive Joe McDonald said the trade evolved when he received a report from Smith about McGee.

“Smith scouted Willie and turned in a good report,” McDonald said to the Post-Dispatch. “We liked his speed and we liked his bat.”

The Yankees looked to trade McGee to get something in return rather than lose him in the Rule 5 draft of players left unprotected on minor-league rosters.

In exploring potential deals, Bergesch told the New York Daily News, “There wasn’t a whole lot of interest in him” except from the Cardinals.

The trade of Sykes for McGee was made the same day the Yankees played the Dodgers in Game 2 of the 1981 World Series and drew little attention.

As good as advertised

McGee was placed on the Cardinals’ 40-man big-league winter roster.

Though he never had played above the Class AA level, he impressed the Cardinals at spring training in 1982.

“He speaks only when spoken to and goes largely unnoticed in the clubhouse,” the Post-Dispatch noted, “but he has skills that have marked him as a soon-to-be major leaguer.”

“Got a quick bat,” said Cardinals manager Whitey Herzog. “It’s unusual to see a young hitter with a quick bat from both sides of the plate.”

Batting from the right side, McGee dazzled by dashing from the plate to first base in 3.9 seconds.

At Yankees training camp, Sykes, weakened by shoulder ailments, was sent to the minors. He’d never pitch in a big-league game for the Yankees.

Upset about receiving what they considered damaged goods, the Yankees wanted the trade voided. “They think they’re going to get McGee back,” Herzog told the Post-Dispatch, “and they’re not.”

Making an impact

McGee began the 1982 season at Louisville. “I thought I was going to play the full year in triple-A to get some experience because I hadn’t played there before,” he told The Sporting News.

The plan changed when Cardinals outfielder David Green tore his right hamstring and was placed on the disabled list on May 8. The Cardinals called up McGee, who had hit .291 in 13 games with Louisville.

From the start, the rookie played like he belonged. He hit .378 for the Cardinals in May and .349 in June.

“I certainly didn’t think he’d be able to come up here and handle the pitching like he has,” Herzog told The Sporting News.

For the season, McGee hit .296 and swiped 24 bases for the Cardinals. He hit .308 in the National League Championship Series versus the Braves, and was the standout of World Series Game 3, with two home runs and two spectacular catches against the Brewers. Boxscore and Video.

On Jan. 24, 1983, the Cardinals traded outfielder Stan Javier and infielder Bobby Meacham to the Yankees for outfielder Bob Helson and pitchers Steve Fincher and Marty Mason. The Post-Dispatch reported the deal was to appease Yankees owner George Steinbrenner, who held hard feelings toward the Cardinals for sending Sykes in exchange for McGee 15 months earlier.

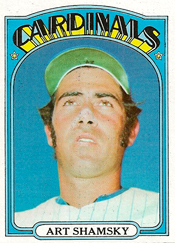

On Oct. 18, 1971, Shamsky was the best-known name among the four players the Cardinals acquired in a trade with the Mets. The Cardinals sent pitchers

On Oct. 18, 1971, Shamsky was the best-known name among the four players the Cardinals acquired in a trade with the Mets. The Cardinals sent pitchers  Described by The Sporting News as “a little stick of a guy who stands 5 feet 10 and weighs 150 pounds” and who “doesn’t show anything in the way of muscles,” Hartenstein was given the nickname Twiggy by a teammate.

Described by The Sporting News as “a little stick of a guy who stands 5 feet 10 and weighs 150 pounds” and who “doesn’t show anything in the way of muscles,” Hartenstein was given the nickname Twiggy by a teammate. On Oct. 15, 1946, Klinger was the Red Sox pitcher who gave up the winning run to the Cardinals in World Series Game 7.

On Oct. 15, 1946, Klinger was the Red Sox pitcher who gave up the winning run to the Cardinals in World Series Game 7. A right-handed pitcher, Cloyd Boyer had an exceptional fastball when he got to the big leagues with the Cardinals, drawing comparisons to ace Mort Cooper, but he wasn’t the same after hurting his shoulder.

A right-handed pitcher, Cloyd Boyer had an exceptional fastball when he got to the big leagues with the Cardinals, drawing comparisons to ace Mort Cooper, but he wasn’t the same after hurting his shoulder. On Oct. 10, 1961, seven Cardinals were chosen in the National League expansion draft. No other club lost more players in filling the rosters of the Houston Colt .45s and New York Mets.

On Oct. 10, 1961, seven Cardinals were chosen in the National League expansion draft. No other club lost more players in filling the rosters of the Houston Colt .45s and New York Mets.