(Updated July 31, 2023)

In a game that brought together the three best National League hit producers _ Hank Aaron, Pete Rose and Stan Musial _ the most prominent catcher of the era started in center field.

On May 17, 1970, Johnny Bench was the Reds’ center fielder in the second game of a doubleheader against the Braves at Cincinnati. For Bench, the National League’s Gold Glove-winning catcher, it was the first time he played the outfield in a major-league game.

On May 17, 1970, Johnny Bench was the Reds’ center fielder in the second game of a doubleheader against the Braves at Cincinnati. For Bench, the National League’s Gold Glove-winning catcher, it was the first time he played the outfield in a major-league game.

Bench fielded flawlessly and hit a home run, helping the Reds complete a doubleheader sweep, but the spotlight was on Aaron, who got his 3,000th career hit in the game.

Musial, the retired Cardinals’ standout and the last player before Aaron to achieve 3,000 hits, was in the stands to witness the feat, and Rose, who would become baseball’s all-time hits leader, was in right field that day for the Reds.

Hot ticket

With Sparky Anderson in his first season as their manager, the Reds won 13 of their first 17 games in 1970. Entering the Sunday doubleheader on May 17, the Reds were 25-10 and five games ahead of the second-place Braves.

A combination of the Reds’ hot start and the chance to possibly see Aaron get his 3,000th hit generated a big turnout at Crosley Field. Swelled by 4,000 standing room-only tickets sold, the doubleheader drew 33,217 spectators, the Reds’ largest home crowd since 36,961 came out for a Sunday doubleheader versus the Pirates on April 27, 1947.

The Braves were playing at Crosley Field for the last time. When they next returned to Cincinnati to open a series on June 30, the Braves were the Reds’ first opponent in the new Riverfront Stadium.

Special support

Aaron got his 2,999th career hit on Saturday afternoon, May 16, at Crosley Field. Musial wanted to be present when Aaron got No. 3,000. Wearing a blue suit, Musial, 49, arrived at the Cincinnati airport at 10:48 on Sunday morning, May 17, stopped to get his shoes shined and headed to Crosley Field.

At 11:55 a.m., Aaron and Musial posed for pictures inside the clubhouse. “They laughed and swapped stories about baseball,” the Atlanta Constitution reported.

As Aaron headed to the field for batting practice, Musial took a front-row box seat next to Braves owner Bill Bartholomay.

In Game 1, Aaron went hitless in four at-bats against Jim Merritt. Bench caught all nine innings and had a RBI in the 5-1 Reds victory. Boxscore

Bold move

Bench, 22, entered Game 2 of the doubleheader with 10 home runs and 30 RBI for the young season. Wanting to keep Bench’s bat in the lineup but not wanting him to catch two games in one day, Sparky Anderson looked to shift Bench to another position in Game 2.

Bench had started three games at first base in place of an ailing Lee May in April, but the Braves were starting a left-hander, George Stone in Game 2, and Anderson wanted all of his right-handed sluggers, Bench, May and third baseman Tony Perez, in the lineup. The Reds’ regular center field, ex-Cardinal Bobby Tolan, batted left.

Bench’s favorite player as a youth was Yankees center fielder and fellow Oklahoman Mickey Mantle, so when Anderson suggested Bench play center field in Game 2, he got an enthusiastic response.

“This sort of fulfills a boyhood dream,” Bench told the Cincinnati Enquirer.

Anderson said, “I believe Bench can play anywhere and do a major-league job. I was going to play him in right field, but he said he has trouble with balls curving away from him. In center, everything is hit straight at you, so he shouldn’t have any trouble.”

Magic moment

The Reds’ starting outfield in Game 2 was Hal McRae in left, Bench in center and Pete Rose in right. Ex-Cardinal Pat Corrales was their catcher. The Reds’ starting pitcher, rookie Wayne Simpson, was 5-1 with a 2.05 ERA.

Aaron, 36, got his 3,000th hit when he faced Simpson, 21, in the first inning. Aaron’s grounder was scooped on the shortstop side of second by second baseman Woody Woodward, who couldn’t make a throw. Felix Millan scored from second on the play. Video

As the crowd gave Aaron a standing ovation, Musial vaulted over the railing in front of his seat and joined him at first base. Photographers snapped pictures of the only living 3,000-hit players.

According to the Dayton Daily News, Musial said to Aaron, “It’s a thrill for me to be here and see this.”

Aaron replied, “I really appreciate your taking the time to come from St. Louis to Cincinnati for this.”

In his autobiography, “I Had a Hammer,” Aaron said, “I was proud to be joining a man I admired so much and pleased to carry on his tradition.”

Musial was playing left field the night Aaron got his first hit in the majors. It came against the Cardinals’ Vic Raschi on April 15, 1954, at Milwaukee.

After witnessing Aaron get his 3,000th hit, Musial told the Cincinnati Enquirer, “Right after I got my 3,000 hits (the milestone came in May 1958), I was playing against the Braves. I was standing around the batting cage and I told Henry he’d be the next man to reach 3,000. It wasn’t too hard to predict. He looked like a great hitter, he could run, and you could see he wasn’t the kind of player who would be injured often.”

Elite group

Hit No. 3,000 for Aaron came in the 2,460th game of his career.

Aaron was the ninth player with 3,000 hits. The others: Cap Anson, Ty Cobb, Tris Speaker, Honus Wagner, Eddie Collins, Nap Lajoie, Paul Waner and Musial.

Aaron was the first to get 3,000 hits and 500 home runs.

Two innings after his 3,000th hit, Aaron hit his 570th home run, a two-run shot against Simpson.

“If he hits like this now,” Simpson said to the Dayton Daily News, “how did he hit 10 years ago? I’m glad I wasn’t pitching then.”

After the game, Aaron told the Atlanta Constitution that Willie Mays and Pete Rose were the most likely to next reach 3,000 hits.

Rose, who played his entire career in the National League, went on to become baseball’s all-time leader in hits (4,256). Cobb, an American Leaguer, is second at 4,189. Aaron ranks third (3,771) and Musial is fourth (3,630).

Aaron had 3,600 hits as a National League player with the Braves and 171 as an American Leaguer with the Brewers. Thus, the top three in career hits in the National League are Rose (a switch-hitter), Musial (who batted left) and Aaron (who batted right).

Versatile and durable

Almost overlooked in the drama surrounding Aaron was the play of Bench in center. He had no problems fielding the position, but in the ninth inning, with the score tied at 3-3, Bench went back to catching and Tolan took over in center.

After the Braves scored three times in the top of the 10th, the Reds rallied against Ron Kline, an ex-Cardinal. Tony Perez stroked his fifth hit of the game, and Bench and Lee May followed with home runs, tying the score at 6-6.

The game reached the 15th inning before 19-year-old rookie Don Gullet, who pitched two scoreless innings, drove in the winning run for the Reds with a single. Boxscore

Nine days later, against the Padres at San Diego, Bench started in center field for the second and last time. Boxscore

In 15 total innings as a center fielder, Bench made three putouts and no errors.

Bench made 17 outfield starts _ eight in left, seven in right and two in center _ in 1970, plus five starts at first base.

In 17 seasons in the majors, Bench made 1,627 starts at catcher, 182 at third base, 98 at first base and 96 in the outfield.

In the book “Season Ticket,” Cardinals catcher Ted Simmons told author Roger Angell that as a catcher “Bench was picture perfect. A marvelous mechanical catcher. There’s no better.”

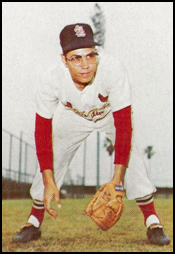

During spring training in 1964, the Cardinals were in the market for a backup catcher and the Braves were seeking a reserve outfielder.

During spring training in 1964, the Cardinals were in the market for a backup catcher and the Braves were seeking a reserve outfielder. In March 1965, the Cardinals were considering trading Javier, their second baseman since 1960. Anderson, three weeks into his job as a manager in the Cardinals’ farm system, spoke up at an organizational staff meeting and advocated for keeping Javier.

In March 1965, the Cardinals were considering trading Javier, their second baseman since 1960. Anderson, three weeks into his job as a manager in the Cardinals’ farm system, spoke up at an organizational staff meeting and advocated for keeping Javier. On Oct. 23, 1996, St. Louis County health officials said four employees of Bartolino’s South restaurant at 5914 South Lindbergh Boulevard were diagnosed with the highly contagious hepatitis A disease.

On Oct. 23, 1996, St. Louis County health officials said four employees of Bartolino’s South restaurant at 5914 South Lindbergh Boulevard were diagnosed with the highly contagious hepatitis A disease. On Oct. 21, 1981, the Cardinals got minor-league outfielder Willie McGee from the Yankees for pitcher Bob Sykes. The Cardinals made the trade on the recommendation of Smith, a Cardinals scout, who watched McGee play for the Yankees’ Nashville farm club and liked what he saw.

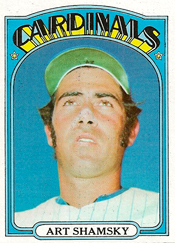

On Oct. 21, 1981, the Cardinals got minor-league outfielder Willie McGee from the Yankees for pitcher Bob Sykes. The Cardinals made the trade on the recommendation of Smith, a Cardinals scout, who watched McGee play for the Yankees’ Nashville farm club and liked what he saw. On Oct. 18, 1971, Shamsky was the best-known name among the four players the Cardinals acquired in a trade with the Mets. The Cardinals sent pitchers

On Oct. 18, 1971, Shamsky was the best-known name among the four players the Cardinals acquired in a trade with the Mets. The Cardinals sent pitchers