On the verge of giving up hope of reaching the major leagues, Ron Allen persevered and was given a chance by the Cardinals.

On Sept. 15, 1971, in a swap of minor-leaguers, the Cardinals acquired Allen from the Mets for third baseman Bobby Etheridge.

On Sept. 15, 1971, in a swap of minor-leaguers, the Cardinals acquired Allen from the Mets for third baseman Bobby Etheridge.

A switch-hitting first baseman, Ron Allen was the younger brother of big-leaguers Dick Allen and Hank Allen.

Dick Allen was a slugger who hit 34 home runs when he played for the Cardinals in 1970.

Ron Allen also had power, but hadn’t advanced out of the minor leagues since he signed with the Phillies in 1964.

In August 1972, nearly a year after the Cardinals dealt for him, Allen was 28 and in his ninth season in the minors when he got the call he had waited for so long.

All in the family

Four Allen brothers, Coy, Hank, Dick (also known as Rich or Richie) and Ron, were all-state high school basketball players in their hometown of Wampum, Pa., according to The Sporting News. All also were baseball standouts.

The oldest brother, Coy, went to work in the steel mills, Ron Allen told the Philadelphia Daily News. Hank, Dick and Ron got other opportunities.

Dick Allen was a 16-year-old amateur shortstop in 1958 when Phillies scout Johnny Ogden first saw him. “I knew this boy could be one of the great hitters,” Ogden told The Sporting News.

Determined to keep Dick Allen from getting away, the Phillies signed Hank Allen, 19, to a $4,000 contract in April 1960. Soon after, Dick Allen, 18, signed with the Phillies for $70,000. Both were right-handed batters.

Ron Allen, 21 months younger than Dick, tried to keep pace with him. A natural left-hander, Ron learned to hit from both sides of the plate in high school.

“We’ve always been as close as two brothers can be, both on and off the field,” Ron Allen told Bill Conlin of the Philadelphia Daily News. “In baseball, I played third and he played short the first two years we played. I hit third and he hit fourth. The year he signed with the Phillies, I hit cleanup and he hit third. I had a better average, around .500, but he hit about seven more homers than me.”

While Hank and Dick pursued professional baseball careers, Ron enrolled at Youngstown State in Ohio.

“Mom was determined there was going to be one Allen who went to college,” Ron told the Philadelphia Daily News. “Mom was pretty set on it.”

A history major, Ron Allen excelled in basketball and baseball at Youngstown State. After his junior year, he signed with the Phillies. At 6 feet 3 and 210 pounds, Ron was a prospect “with good power,” the Philadelphia Inquirer noted.

That same year, Dick Allen became the first of the Allen brothers to reach the majors, and he made an impact. Dick led the National League in extra-base hits and total bases in 1964 and won the Rookie of the Year Award.

Two years later, Hank Allen got to the big leagues with the Senators.

Down on the farm

Ron Allen spent his first three seasons (1964-66) in the Phillies’ system at the Class A level. At spring training in 1967, the Philadelphia Daily News reported, “No man in the Phillies camp can propel a baseball further than” Ron Allen, but “the rap on his hitting is he swings at too many bad balls and strikes out too much.”

“All I want to do is get to the big leagues,” Ron said. “I’ll shine shoes to get there if I have to.”

While Dick Allen thrived as a big-league slugger, Ron remained stuck in the minors. His sixth and best season in the Phillies’ system came in 1969 when he hit .300 with 25 home runs and 97 RBI for Class AA Reading.

After the season, Dick Allen, who had run-ins with Phillies management, was traded to the Cardinals.

Ron Allen, who spent winters working as a draftsman for the city engineering department in Youngstown, reported to Phillies spring training in 1970, but didn’t impress. “I don’t think he’s going to hit good pitching,” farm director Paul Owens told Stan Hochman of the Philadelphia Daily News.

On April 10, 1970, the Phillies traded Ron Allen to the Mets.

“I knew the Phillies wouldn’t give me a chance,” Ron told United Press International. “They said one Allen is enough. I was really happy to be traded.”

The Mets assigned him to the minor leagues. He hit 21 home runs in the Mets’ farm system in 1970 and 20 the next year before the Cardinals acquired him after the completion of the 1971 minor-league season.

The wait ends

Assigned to the Cardinals’ Class AAA Tulsa team in 1972, Ron hit .267 with 16 home runs and 51 RBI in 103 games.

On Aug, 7, 1972, the Cardinals released backup first baseman Donn Clendenon and opted to call up Ron to replace him.

Cardinals director of player development Bob Kennedy said Ron told him he had been considering quitting baseball, the St. Louis Post-Dispatch reported.

Elated by the promotion, Ron said to Kennedy, “I don’t want four or five years in the major leagues. I just want one swing.”

Four nights later, on Aug. 11 against the Pirates, Ron made his major-league debut. Batting for pitcher Lowell Palmer, he struck out versus ex-Cardinal Nelson Briles. Boxscore

On Aug. 13, in the second game of a doubleheader against the Pirates, Ron started for the first time in the majors. Playing first base in place of Matty Alou, he was hitless in four at-bats versus Steve Blass. Boxscore

Ron’s highlight came on Aug. 17 at San Diego against the Padres. He entered the game in the eighth inning after Joe Torre, playing first base for an injured Alou, was ejected.

Leading off the ninth, Ron got his first big-league hit, a home run to right against reliever Mike Corkins.

“Allen hit a good pitch, low and away,” Corkins told the Post-Dispatch. “He used to hurt me in the minors, too.” Boxscore

Life after baseball

The home run was Allen’s only hit in the majors. In 14 plate appearances for the Cardinals, Ron had three walks and one hit, batting .091. The Cardinals released him to Tulsa on Sept. 5, 1972. Having achieved his goal of reaching the majors, Ron retired from baseball.

Ron told United Press International he was “grateful for what I got. It’s been a constant struggle just to make it to the top.”

That same year, Dick Allen, playing for the White Sox, led the American League in home runs and RBI, and won the Most Valuable Player Award. Hank Allen also played for the White Sox that season.

Hank finished his big-league career in 1973 and Dick’s last season was 1977.

Hank became a thoroughbred horse trainer and Ron was his stable foreman, according to the Los Angeles Times. In 1989, Northern Wolf, a horse trained by Hank, raced in the Kentucky Derby and Preakness.

Ron was inducted into the Youngstown State athletic hall of fame in 1990.

In 2010, when he was 66, Ron fulfilled a promise made to his mother and completed his college education, earning a bachelor’s degree in general studies from Youngstown State.

On Sept. 10, 1981, the Cardinals acquired Bair from the Reds for infielder Neil Fiala and pitcher Joe Edelen.

On Sept. 10, 1981, the Cardinals acquired Bair from the Reds for infielder Neil Fiala and pitcher Joe Edelen. On Sept. 6, 1971, during a game between the Cardinals and Phillies at Philadelphia, McCarver punched Brock in the face on the field at Veterans Stadium. Brock fought back, swinging at McCarver and landing a couple of shots, before they wrestled to the ground and were separated.

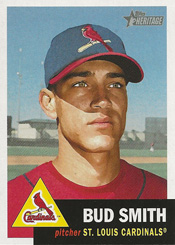

On Sept. 6, 1971, during a game between the Cardinals and Phillies at Philadelphia, McCarver punched Brock in the face on the field at Veterans Stadium. Brock fought back, swinging at McCarver and landing a couple of shots, before they wrestled to the ground and were separated. On Sept. 3, 2001, Smith pitched a no-hitter for the Cardinals against the Padres.

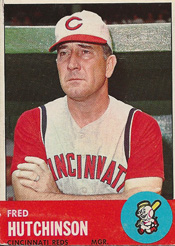

On Sept. 3, 2001, Smith pitched a no-hitter for the Cardinals against the Padres. On Aug. 18, 1961, Reds manager Fred Hutchinson used a shortwave radio to communicate instructions from the bench to his third-base coach.

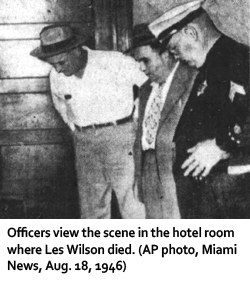

On Aug. 18, 1961, Reds manager Fred Hutchinson used a shortwave radio to communicate instructions from the bench to his third-base coach. On Aug. 17, 1946, Wilson, 35, died after a hellish night of hallucinations and destructive drinking.

On Aug. 17, 1946, Wilson, 35, died after a hellish night of hallucinations and destructive drinking.