(Updated Oct. 6, 2024)

Adding a mix of controversy and comedy with a demonstration of clout, baseball’s greatest showman gave a commanding performance while reaching a milestone before a St. Louis audience.

On Aug. 21, 1931, in a game against the Browns at Sportsman’s Park, Yankees slugger Babe Ruth hit his 600th career home run.

On Aug. 21, 1931, in a game against the Browns at Sportsman’s Park, Yankees slugger Babe Ruth hit his 600th career home run.

Usually, such a feat would provide enough drama for one day, but not for Babe. Next, he got ejected. Then, he sparked a treasure hunt by offering a reward for his home run ball.

Big blow

Ruth, 36, hit his 599th home run, a ninth-inning grand slam, on Aug. 20 against the Browns at Sportsman’s Park. Boxscore

The next day, a Depression Era crowd of 4,000 came to Sportsman’s Park to see if he could hit No. 600.

Before the game, Ruth informed Browns secretary Willis Johnson he’d like to have the ball if he hit the milestone home run, the St. Louis Globe-Democrat reported.

In the third inning, with a runner on first, Ruth did his part. He hit a pitch from George Blaeholder high and deep to right, “a gorgeous, virile blow” that “stirred the sopranos to violent shrilling,” the New York Daily News noted.

The ball carried over the pavilion roof and struck a parked car on Grand Avenue, according to the Associated Press.

“The din had just subsided” when Lou Gehrig “duplicated the Bambino’s feat,” the Daily News reported. According to the St. Louis Post-Dispatch, Gehrig’s ball bounced off the roof and into the street.

Prize money

Four innings later, with the Yankees ahead, 8-1, Browns cleanup batter Red Kress hit a three-run home run to left against Hank Johnson.

Ruth, playing left field, claimed a spectator in the bleachers interfered with the ball while it was in play. When Ruth persisted with his argument, umpire Roy Van Graflan ejected him. It was the 10th of Ruth’s 11 career ejections as a player, but only the second time the gate attraction had been tossed since 1924.

Done for the day, Ruth’s thoughts were on his home run ball. When he got to the clubhouse, he sent word to the press box, asking that radio stations relay his request for the ball to be returned to him. Ruth said he would reward the finder with $10 and a new baseball.

Ruth was drawing a salary of $80,000 in 1931 _ when asked after signing the contract whether he believed he deserved to be making more money than President Herbert Hoover, Babe supposedly replied, “’I had a better year than he did.” _ but a $10 offer for a baseball was a good deal during the depths of economic depression.

Three St. Louis radio stations (KMOX, KWK and WIL) carried Browns home games in 1931, so when Ruth’s request went on the airwaves it reached a wide audience.

Kid stuff

When a 10-year-old newsboy, Tom Collico of North Grand Avenue, showed up at the Sportsman’s Park press gate with a ball, Willis Johnson, the Browns’ secretary, took him to meet Ruth.

According to Dick Farrington of The Sporting News, “Babe greeted the kid like a father. He fished around and handed the boy a $10 bill and in another few minutes had a brand new ball for him.”

While Collico was meeting with writers in the press box, another boy arrived at the gate and said he had the Ruth home run ball. According to The Sporting News, the boy was brought to Ruth, who gave him $10 and a new ball, too.

“Babe doesn’t know which of the balls he purchased was the one he hit,” The Sporting News noted.

Ruth guessed one of the balls was Gehrig’s home run. Boxscore

Ruth finished the season with 46 home runs, the 12th and last time he led the American League in that category.

Against the Browns in 1931, he hit .383 with eight home runs, including four at Sportsman’s Park.

For his career, Ruth batted .351 with 96 home runs versus the Browns. He hit 58 regular-season home runs at Sportsman’s Park. He also hit six there against the Cardinals _ three in Game 4 of the 1926 World Series Boxscore and three in Game 4 of the 1928 World Series. Boxscore

On Aug. 14, 1971, Gibson got his lone no-hitter when he struck out Stargell for the last out.

On Aug. 14, 1971, Gibson got his lone no-hitter when he struck out Stargell for the last out. On Aug. 10, 2001, Cairo signed with the Cardinals after he was placed on waivers by the Cubs.

On Aug. 10, 2001, Cairo signed with the Cardinals after he was placed on waivers by the Cubs. On Aug. 11, 2011, the Cardinals signed Rhodes after he was released by the Rangers. Two months later, the Cardinals beat the Rangers in an epic seven-game World Series.

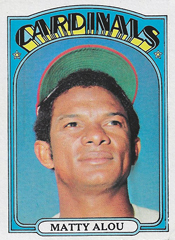

On Aug. 11, 2011, the Cardinals signed Rhodes after he was released by the Rangers. Two months later, the Cardinals beat the Rangers in an epic seven-game World Series. On Aug. 7, 1971, Alou used skill, imagination and nerve to produce the winning run for the Cardinals in a victory versus the Dodgers at St. Louis.

On Aug. 7, 1971, Alou used skill, imagination and nerve to produce the winning run for the Cardinals in a victory versus the Dodgers at St. Louis. At 5 feet 7, 154 pounds, Pickles was a gherkin who played a position filled with hulks. What he lacked in size he made up for in spirit. Aggressive and energetic, Dillhoefer was popular with teammates and fans.

At 5 feet 7, 154 pounds, Pickles was a gherkin who played a position filled with hulks. What he lacked in size he made up for in spirit. Aggressive and energetic, Dillhoefer was popular with teammates and fans.